Appetite

Hungry Games: How Does Hunger Affect Your Politics?

The effect of hunger on us is powerful politically, but...

Posted December 1, 2013

I’m still stuffed from Thanksgiving dinner. Turkey, dressing, cranberry sauce (the best kind, from a can), green bean casserole, pumpkin pie… I’m so fortunate. If I didn’t consume more than my fair share of holiday calories, it was not for lack of effort.

* * * * *

Hmmm…

The average holiday dinner alone can carry a load of 3,000 calories. And most of us nibble our way through more than another 1,500 calories downing dips and chips and drinks before and after the big meal. Combined, that's the equivalent of more than 2 1/4 times the average daily calorie intake.

-- The Calorie Control Council, an international association founded in 1966 to represent the reduced-calorie food and beverage industry

* * * * *

Given my current stuffed state, I’m pretty sure interesting research by my political psychology colleagues Michael Bang Peterson, Lene Aarøe, Niels Holm Jensen, and Oliver Curry doesn’t apply to me right now. This research group is interested in how evolutionary and biological forces, in this case, hunger, affect people’s attitudes about redistributive social welfare policies.

Hungry Hunter-Gatherers

Evolutionary theory suggests people are motivated to act in ways that increase their probability of survival in order to pass more of their genes into the population through reproduction (see some of my previous posts on disgust, fear of immigrants, leader stature and sex, brain hemisphere integration, and even locker room bullying). It doesn't take a Noble Prize in biology to know there aren’t too many issues more important to survival than having enough to eat.

Anthropological evidence suggests that hunger was common in human ancestral history and that both humans and non-human animals shared food, even with non-relatives, to overcome food shortages. Because of this long record of food sharing, the research group speculated that a psychological mechanism for peaceful food sharing evolved to reduce the likelihood that people will acquire food through force or violence from other group members.

“Please help!”

With this evolutionary perspective in mind, the team of researchers hypothesized hungry people would be more likely to voice support for “resource sharing” via social welfare policies than people who are not hungry; that is, they would be more willing to remind others of the importance of sharing.

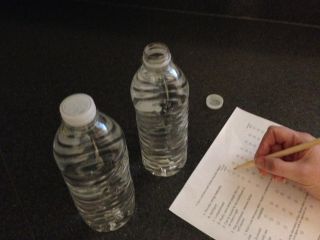

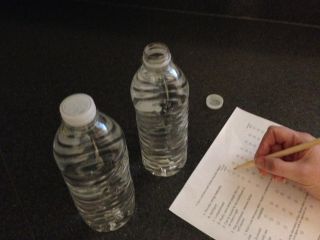

Aarøe and Petersen

Aarøe and Petersen

“Talk is cheap”

As they suspected based on their evolutionary expectations, Aarøe and Petersen found the hungry subjects indeed were more likely to express support for the social welfare policies than their satiated opposites. That is, they were more willing to signal others about the importance of resource sharing. On the other hand, they found that hungry subjects, despite being more likely to say sharing is important, were not statistically more likely to actually share the cash resource than the satiated subjects. This suggests people will send signals to try to trigger peaceful sharing, but in the end they will hoard important resources for themselves. Put otherwise, as Aarøe and Petersen concluded, “talk is cheap.”

Appreciatively Yours

This is really interesting research that focuses on the political attitudes and behavior of “hungry” people. It shows how powerful the effect of hunger can be, even though the physical state caused by the experiment cannot even begin to capture the distress experienced by people who really don’t have enough to eat.

Writing about this reminds me how very fortunate I am not to be hungry. I hope you, too, find yourself in a position of abundance.

Here are a few highly ranked charities from Charity Navigator that help people who struggle to find enough to eat:

You might find these to be worthwhile organizations that can help the fortunate share resources with the less fortunate during this season of giving.

- - - - - - -

For more information:

Aarøe & Petersen. Forthcoming. "Hunger Games: Fluctuations in Blood Glucose Levels Influence Support for Social Welfare." Psychological Science doi:10.1177/0956797613495244.

Petersen, Aarøe, Jensen, & Curry. Forthcoming. "Social Welfare and the Psychology of Food Sharing: Short-Term Hunger Increases Support for Social Welfare." Political Psychology doi: 10.1111/pops.12062.

In addition to writing the "Caveman Politics" blog for Psychology Today, Gregg is the Executive Director of the Association for Politics and the Life Sciences and an Associate Professor of Political Science at Texas Tech University.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it by email or on Facebook or Twitter. Follow Gregg on Twitter @GreggRMurray or “Like” him on Facebook to see notes on other interesting research. You can find more information on Gregg at GreggRMurray.com.