Decision-Making

Exploring Brain Processes During Basic Decision-Making

How does the brain represent the different dimensions of a decision problem?

Posted October 7, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Basic decision-making requires comparing options. Evaluating an option necessitates assessing many dimensions.

- Some dimensions of a decision, such as taste, are easy to compute. Others require cognitive resources.

- Different brain systems specialize in different calculations. Not all calculations always take place.

- When calculations do not take place, we tend to make impulsive or unhealthy choices

Betty faces a seemingly simple choice between an apple and a donut. But as we'll soon discover, the brain's decision-making process is far from straightforward.

Betty is standing before the healthy apple and the delectable donut. She is also following a diet to reduce her risk of developing hypertension. What happens next? Well, her brain springs into action and processes visual information. This visual processing begins in her visual cortex, located at the back of her brain. Her brain also considers sensory information like smell and texture, merging it with what she sees.

Betty's brain then evaluates these inputs through a multi-step process involving memory retrieval, anticipation of consequences, and freshness assessment, all contributing to the valuation process. These processes lead to sending information to Betty's core value system, which ultimately guides her choice.

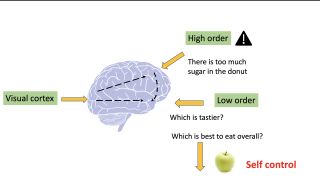

Not all information is treated equally by the brain. In a simplified view, there are two categories: low-order concerns, like tastiness, are rapidly processed in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Meanwhile, higher-order concerns, such as health consequences, are routed through the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a region involved in cognition and regulatory mechanisms. Processing higher-order concerns demands cognitive resources and time.

In this example, when Betty assesses the tastiness of the food, her well-honed visual system quickly sends information to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which evaluates which option is tastier. But when cognitive resources come into play, higher-order concerns are also processed with the help of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Health consequences are scrutinized, and this information is then passed back to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which determines the best choice considering all concerns.

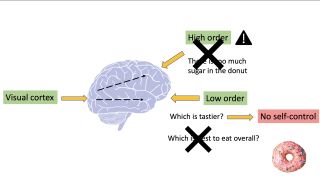

Betty exercises self-control when the extra tastiness of the donut isn't worth the added health consequence. In this case, she makes the healthy choice. However, Betty might also succumb to impulsive desires, especially when distractions or limited cognitive resources are at play. In these cases, higher-order concerns may be overlooked, and the donut becomes irresistible.

This intricate decision-making process extends to all choices in life. Whether it's deciding to study for an exam or watch a movie, we're constantly weighing immediate costs against long-term consequences. Saving or spending money involves similar trade-offs. Our brain does not weigh immediate and delayed rewards the same way, which may result in a bias toward the least difficult to evaluate: immediate rewards.

Several factors influence these processes. Age is a significant player, with cognitive systems related to higher-order concerns developing and maturing late in adolescence. This explains why young children and teenagers tend to be more impulsive. On the flip side, these systems age the earliest, leading to impaired decision-making in older adults.

Importantly, these processes can go awry. Dysfunctional evaluations of both low-order and high-order concerns are observed in various behavioral disorders. For example, eating disorders frequently stem from self-regulation challenges and imbalances within these brain regions. Individuals with anorexia may experience overstimulation of regions associated with higher-order concerns, while the opposite may occur in those dealing with bulimia. In cases of obesity, the brain becomes hypersensitive to food-related stimuli, while regions responsible for assessing higher-order considerations exhibit deficits.

Dysfunctions of the reward system and cognitive processes have been observed in a variety of behavioral disorders grouped under the umbrella of Impulsive Compulsive Spectrum Disorders and characterized by maladaptive impulses and/or an impairment of cognitive regions. Patients with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) often struggle to consider the consequences of their actions and frequently act impulsively, prioritizing immediate rewards or costs.

Addiction serves as another example of an imbalance within the systems responsible for evaluating both low-order and high-order considerations. Extensive research into the consumption patterns of people with an addiction reveals that it disrupts functions in both these areas. Comparable observations have surfaced within the context of behavioral addictions.

In conclusion, the next time you're faced with a choice, whether it's as simple as Betty's apple vs. donut dilemma or one that's more complex, remember that your brain is a remarkably intricate machine. It's also a battleground where immediate desires clash with long-term consequences. Understanding this intricate dance can empower you to make more informed decisions, just like Betty does when she chooses the apple.

References

I. Brocas and J. Carrillo, “Value computation and modulation: a neuroeconomic theory of self-control as constrained optimization”, Journal of Economic Theory, 198, 105366, 2021. PDF

Value Based Decision-making, LABEL laboratory, YouTube video