Fantasies

How People Make Their Wishes Come True

Our wishes can offer extraordinary insights into ourselves.

Posted August 17, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- People's wishes are often a reflection of their needs.

- Fantasizing about fulfilling a wish can sometimes hinder the pursuit of the wish.

- Contrasting positive fantasies with relevant internal obstacles can motivate people to devise plans to overcome hurdles and pursue their wishes.

One of Chekhov’s fictional heroes—a venerable professor of medicine—had a peculiar method for gaining insight into people. He considered their wishes. “Tell me what you want,” he would bid, “and I will tell you who you are.”

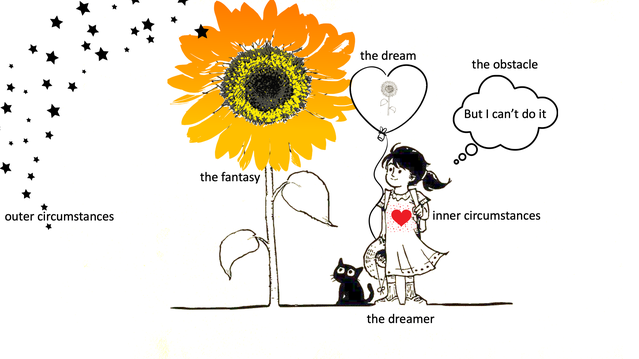

Much like the masters of arts and letters, psychologists have long been captivated with the why and how of our dreams. For over two decades, NYU psychologist Gabriele Oettingen has been researching the curious mechanisms of wish fulfillment, from inception to realization. The tale of every wish, it appears, revolves around the journey of four main protagonists: the dreamer, the dream, the fantasy, and the obstacle. The backdrop against which these protagonists are traveling is a tapestry of countless constellations of outer and inner circumstances.

Having studied thousands of participants, Oettingen and her colleagues discovered that upon making a wish, people typically followed one of these self-regulatory cognitive patterns:

- Spend many pleasant hours in positive fantasies by imagining themselves fulfilling their dreams (indulging).

- Brood over all possible obstacles standing between them and their dreams (dwelling).

- First fantasize about their desired future, then explore the obstacles (mental contrasting).

- First explore the obstacles, then fantasize about the desired future (reverse contrasting).

Positive Fantasies as a Double-Edged Sword

All of us dreamers visualize our dreams coming true. Perhaps that’s why one of Oettingen’s biggest surprises was finding what exactly these positive fantasies were doing to people who were indulging in them. The data was clear: the very images that allowed us to virtually live through our hearts’ desires were having hampering effects on their realization.

“In the beginning, we were so surprised to see this tendency, that I thought I must have made a mistake,” says Oettingen. Only after continuous replication of the studies with similar results did Oettingen and her colleagues recognize that they had come across a real phenomenon.

Why would fantasizing about fulfilling a wish hinder the pursuit of the wish?

Let’s say that your long-standing wish is to publish a book. When you picture yourself with your bestseller already in your hands, standing in front of an applauding audience as you accept an award for your literary success while reporters queue up to ask you questions, you experience a “mental attainment” of your wish. In your mind’s eye, you have already experienced the rewards of having achieved your dream. This virtual simulation of fulfillment can have a relaxing effect, making people exert less energy and effort that is actually required to turn their wishes into reality.

Oettingen and her colleagues tested this hypothesis. Indeed, participants who indulged in positive fantasies about winning a lot of money behaved like they were financially satiated and chose to forego an immediate monetary reward for a larger one in the future (Sciarappo, Norton, Oettingen, & Gollwitzer, 2015). Apparently, after having tasted winning the monetary prize in their fantasies and mentally attaining their desired future, they were not as concerned about receiving the money from the experimenters right then and there.

Why Mental Contrasting Can Help You Achieve Your Dreams

How can we offset the counterintuitive “problem” with positive fantasies and their tendency to dampen our drive to go after our dreams?

That’s where mental contrasting comes in.

“To get people out of their fantasies and give them the energy to pursue their dreams, we realized that we needed to give them a healthy dose of reality,” says Oettingen.

This came in the form of an obstacle that people could identify in themselves that stood in the way of their wishes. When a positive fantasy is contrasted with relevant internal obstacles, a connection is established, linking the desired future with the reality, and the reality (obstacle) with appropriate behavior to overcome it. This non-conscious process, according to Oettingen, can help generate energy by motivating people to devise binding goals, intentions, and appropriate plans to move past hurdles and pursue their wishes. If the expectations of success are high, people commit to the path of attaining their wishes; if they are low, the wishes will be abandoned or postponed.

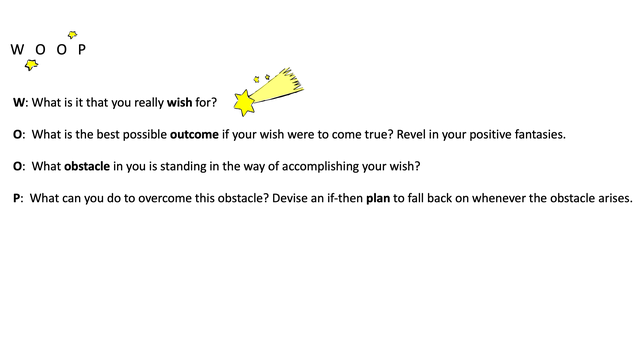

Wish Outcome Obstacle Plan

One of the most widely studied wish-fulfillment strategies born from Oettingen’s research is WOOP (Wish Outcome Obstacle Plan). WOOP is mental contrasting in action. It’s the space where the four protagonists come together to get to know one another before embarking on their journey.

Oettingen calls WOOP a “change agent.”

“If you see something in the world that you want, something that is challenging yet feasible because you have some agency over it, WOOP gives you a framework for turning your positive fantasies into reality,” says Oettingen, who has used WOOP to accomplish many of her own wishes.

Get to Know Your Wishes—and Your Obstacles

An intimate exploration of our wish inventory through tools such as WOOP can offer extraordinary insights into ourselves.

For example, peek behind your dreams and you are likely to stumble upon some psychological need.

Oettingen and her colleagues observed this phenomenon in a series of studies. In one experiment, they asked participants not to drink any liquids for four hours before visiting their lab, where they were offered salty pretzels. Half of the participants got water, and the other half were kept thirsty. Results showed that the positive fantasies of those who were kept thirsty revolved around quenching their thirst. Those who had been allowed to drink, on the other hand, fantasized about events unrelated to water.

Similar outcomes were obtained with experiments conducted with psychological needs.

“When we instilled a need for meaning, people started positively fantasizing about getting a more meaningful job. When we instilled a need for relatedness, people fantasized about getting together with friends and family,” says Oettingen. “Thus, the fantasies are often an expression of what we don’t have.”

Other than understanding our deepest needs, exploring our wishes can also make us face the inner resistance that’s preventing us from realizing them.

Peeking behind those, too, might be an eye-opening endeavor.

“Behind the obstacles are often emotions, irrational beliefs, bad habits, or old hang-ups which we have been carrying with us for years,” explains Oettingen.

Thus, Oettingen’s advice: spend some time in the company of your wishes. Give them your full attention and listen carefully—with an open heart.

“Take 5-10 minutes of quiet to ask yourself one question: What do I really want? Find a wish that’s dear to your heart, in whatever life domain it may be. The key is to ask this question and patiently feel out the answer. Often, people don’t know what they want, or are told what they want. Remember, you are the expert of your life. You have your own needs and desires. Pay attention to your positive fantasies. They are vitally important because they give the action a direction. They represent a desired future, where you want to go and where you want to be.

"Once you have a wish, explore how you would feel already being there. Happy? Relieved? Pinpoint the best outcome and vividly imagine it by experiencing it in your mind. Only then, switch to the obstacle—what is it in you that stands in the way of realizing your wish? Try scratching at the surface and go deeper to understand what is behind your obstacle. You might discover that what you thought was keeping you from fulfilling your wish was not external as you always thought, but an internal resistance. It’s very helpful to gain clarity about what it is in yourself that’s truly standing between you and your dreams, because it will help you assess ways to overcome your obstacle. It could also help you recognize that surmounting the obstacle is too costly for now, or even impossible. But if you feel like the obstacle is surmountable, then it’ll give you the drive to pack away the excuses, step out of the fantasy, and go after your dreams.”

As much joy and fulfillment we anticipate at the end of our wish-fulfillment journey, we would be remiss to ignore the jewels we encounter along the way—bravery and patience, creativity and flow, good intentions, and self-compassion. Perhaps, then, the biggest reward of pursuing our dreams lies in the fortuity to nurture our relationship with ourselves.

Many thanks to Dr. Gabriele Oettingen for her time and insights. Dr. Oettingen is a professor of psychology at NYU. She is the author of Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the New Science of Motivation (2014).

LinkedIn image: Michaelpuche/Shutterstock

References

Oettingen, G. & Sevincer, A. T. (2018). Fantasy about the future as friend and foe. In G. Oettingen, A. T. Sevincer, & P. M. Gollwitzer (Eds.), The psychology of thinking about the future (pp. 127–149). New York, NY: Guilford.

Oettingen, G., & Mayer, D. (2002). The motivating function of thinking about the future: Expectations versus fantasies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1198–1212.

Kappes, H. B., & Oettingen, G. (2011). Positive fantasies about idealized futures sap energy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(4), 719-729.

Sciarappo, Norton, Oettingen, & Gollwitzer (2015) in Oettingen, G., & Reininger, K. M. (2016). The power of prospection: Mental contrasting and behavior change. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(11), 591-604.