Beauty

Why Are Symmetrical Faces So Attractive?

There is a surprising reason we are drawn toward symmetry, especially in faces.

Posted July 8, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

What constitutes beauty?

Among cultures and through history, standards of beauty have changed considerably. At certain times, stoutness was a symbol of wealth and influence and thus was considered attractive. At other times, hardy physical fitness was the gold standard. Different variations of skin tone, facial hair (men), breast size (women), eye color, hair texture, color, and style have all experienced wide swings in their perceived attractiveness at different points in history and in different places.

When it comes to physical attraction, cultural forces far outweigh biological ones, but there are a couple of features that seem to cut through the cultural conditioning and are seen as universally attractive. (Read about how our brain computes attraction.)

For example, across cultures and times, height is reliably rated as desirable in men. For women, a low waist-hip ratio is seen as attractive globally. Of course, these two features are each just one aspect within a full suite of qualities for a specific person and do not overpower everything else. However, there is indeed something special about them simply because they are so universal while most other "attractive features" are not.

There is another feature that drives perceptions of attractiveness and does so almost equally among men and women: facial symmetry. Across many clever experimental designs, researchers have confirmed that we rate faces that are more symmetrical as more attractive than those with less symmetry.

Like height in males and waist-hip ratio in females, symmetrical faces are more attractive to people across cultures and historical times. But where does this biological attraction to facial symmetry come from? First, we must consider how symmetry develops.

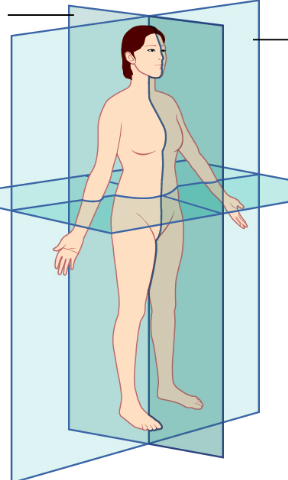

Like all vertebrates, humans have bilateral symmetry about the sagittal plane. For the most part, our right side develops as a mirror image of our left side.

Beginning during embryonic development and continuing through growth and maturity, the same developmental genes should be activated in the same cells, at the same time, and with the same dosage. In the ideal situation, all of that unfolds identically in the left and right sides of our faces, leading to perfect symmetry between the two halves.

Of course, in the real world, the tiniest fluctuations in gene expression and cellular activity lead to small differences between the two halves of our face.

Look closely at your face in the mirror (or a friend’s face). You can usually see that one eye is slightly larger than the other. The larger eye is also usually higher. The nostrils usually show asymmetry in their size and shape as well, and the height and size of the ears can be surprisingly asymmetric also.

All of this asymmetry adds up to a symmetry score for each human face, and these symmetry scores strongly influence how attractively we rate faces. Using CGI, researchers can transform an image of a face that most people rate as highly attractive into one that rates poorly simply by tweaking the symmetry.

But why do we find symmetrical faces more attractive? The dominant scientific explanation for the attractiveness of facial symmetry is sometimes called “Evolutionary Advantage Theory.” If the grand choreography of developmental gene expression is perfectly executed, the result is perfect symmetry.

Therefore, anything less than perfect symmetry indicates some kind of dysfunction, however small. If, on one side of the face, a gene gets expressed too much or too little, in slightly the wrong place, or a bit early or late, the tissue will take shape in a slightly different pattern than on the other side. Most of these small fluctuations result in what is called micro-asymmetry, which we can’t detect with the naked eye (but which we may be subconsciously aware of).

However, larger differences in symmetry may indicate issues that have occurred (or are ongoing) with the growth and development of the individual. Some factors that are known to affect facial symmetry are infections, inflammation, allergic reactions, injuries, mutations, chronic stress, malnourishment, DNA damage, parasites, and genetic and metabolic diseases. Each of these is a potential handicap to the success of the individual and possibly his or her offspring.

While the resulting facial asymmetry is probably the least of the person’s worries, the rest of us respond negatively to it, because it could indicate reduced fitness. Since mating strategies invariably involve the pursuit of the highest quality mate possible, facial asymmetry knocks someone down a few pegs in terms of their attractiveness. This is the currently dominant thinking about why humans strongly prefer symmetry in each other’s faces.

The preference for symmetrical faces is not limited to sexual attraction and mate selection. Facial symmetry appears to influence how we pursue friends and allies as well.

Of course, we all want a “high-quality” mate and co-parent of our children, but we also want friends that are high quality and, dare I say it, high status. It’s an awful thing about us, but everyone wants to be friends with the rich, powerful, and popular.

This reality has become crystal clear in today’s society where people can be “famous for being famous,” having produced essentially nothing of value to anyone and possessing no identifiable skills, talents, or accomplishments and still somehow be known as an important “influencer.” I digress.

It's not altogether surprising that we, as a species, would read so much into faces. We speak face-to-face, and we spend a lot of time looking at each other's faces even when we're not in a conversation. We also have an exceptional degree of diversity in our faces, and this probably comes from the face-centric nature of our social interactions.

In sum, facial symmetry is universally associated with beauty and attractiveness in both sexes and in sexual and non-sexual contexts. The most well-supported theory for this is that our species has evolved to recognize symmetry, if unconsciously, as a proxy for good genes and physical health. This gives us a tentative answer to the question: What’s in a face?

Facebook image: Nadino/Shutterstock