Philosophy

The Life of the Buddha

Prince Siddharta had never seen old age, infirmity, or death.

Updated May 4, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Siddharta renounced everything to take up the life of a wandering ascetic.

- Six years later, he attained enlightenment while sitting beneath a peepul tree.

- For the next 45 years, the Buddha spread his teachings across northeast India.

Next, I will discuss Buddhist philosophy and the Buddhist solution to suffering. But before I do, I wanted to relate Buddha's life—which, if nothing else, is a marvelous story.

The Buddha’s dates are uncertain and range from 624 BCE (earliest birth) to 368 BCE (latest death). Whatever his dates, he began as a wandering ascetic and lived for some 80 years. His movement, Buddhism, arose in reaction to the increasing remoteness and abstruseness of Vedic Brahmanism. His followers deified him and, accordingly, mythologized his life; and it would be profitless to try, if that were possible, to separate the mythology from the reality.

Birth

According to tradition, Siddharta Gautama, later known as the Buddha, was born in Lumbini, in what is now southern Nepal, to King Shuddhodana of the Shakya clan. His mother, Mahamaya, dreamt of a white elephant with six tusks entering her right side. Ten lunar months later, while strolling in a garden in Lumbini, she grabbed onto the drooping branch of a sal tree, and Siddharta ("He who has achieved his aim") emerged fully formed from under her right arm. Siddharta proceeded to take seven steps before announcing that this would be his last life.

Early Years

Seven days later, Mahamaya died. The court astrologers predicted that Siddharta would become either a chakravartin (universal monarch) or a buddha (enlightened one). Not wishing to lose his son and heir—and, at that, a future chakravartin—to a life of renunciation, Shuddhodana confined him to a life of luxury within the precinct of the palace, where he would not be exposed to religious teaching or human suffering. At the age of 16, Siddharta married the beautiful princess Yashodara, and everything seemed on track for Shuddhodana.

First Contact With Old Age, Infirmity, and Death

But at the age of 29, having tired of the delights of the royal kitchen and harem, Siddharta asked to make a chariot ride through the city. The king agreed but had all the old, infirm, and otherwise poor cleared from the route. Even so, Siddharta did, for the very first time, catch a glimpse of an old man. He asked Channa, his charioteer: “Am I also subject to this?”

With his curiosity piqued, Siddharta made three more outings, seeing, in turn, a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and, finally, a meditating mendicant, whose serene smile inspired him to join the path in search of freedom from suffering.

Renunciation and the Path to Enlightenment

Siddharta renounced his position, wealth, and family to take up the life of a wandering ascetic. As night fell and he prepared to make his escape, he was told that a son had been born to him. He went into Yashodara’s chamber to look upon his sleeping wife and son and named the boy Rahula (“Fetter,” on the path to enlightenment). Having crossed the Anoma River into the forest, he sent back the faithful Channa along with his weapons, jewels, and hair. He even sent back his beloved horse, Kanthaka, who died from a broken heart.

In the forest, Siddharta adopted the life of a mendicant, or beggar. For the next six years, he practised successively under two meditation teachers. With five friends, he subjected himself to extreme forms of self-mortification, gradually reducing his daily meal to a single grain of rice.

One day, he accepted a bowl of kheera (milk-rice pudding) from a farmer’s wife called Sujata, who had mistaken the skeletal waif for a wish-granting tree spirit. With some food in the belly, he concluded that extreme asceticism would not advance him along the path to freedom from suffering, but serve only to cloud his mind.

Enlightenment

On the full moon of May, six years after having left the palace, the 35-year-old Siddharta sat in meditation under a peepul tree. The demon Mara tried to disrupt him, including by sending his daughters to seduce him.

When Mara challenged his right to occupy the ground on which he sat, he touched the earth with his right hand, and the goddess of the earth confirmed with a tremor that he had earned this right—on account of a great gift that he had made in his previous life as Prince Vessantara.

Through the night, he had visions of his past lives. Then, at dawn, he reached enlightenment and became a Buddha.

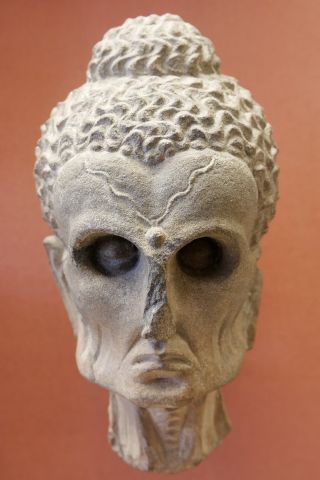

The peepul tree, Ficus religiosa, is now better known as the Bodhi tree, and the place where the Buddha sat in meditation as Bodh Gaya (“Place of Enlightenment”). Representations of the Buddha often include his earth-touching gesture, known as the bhumiparsha mudra.

First Sermons

The Buddha remained in the vicinity of the Bodhi tree to savour his enlightenment. When a seven-day storm blew up, the serpent king Mucalinda encircled him seven times with his coils and sheltered him with his seven-headed hood.

After seven weeks (note the preponderance of the number seven), the Buddha got up to teach. He delivered his first sermon in the deer park at Sarnath, on the outskirts of Kashi (modern-day Varanasi), preaching the Middle Way between luxury and austerity, the Four Noble Truths, and the Eightfold Path.

In his second sermon, he presented his doctrine of anatman (no-self). So eloquently did he speak that, upon hearing him, his five ascetic friends rose up into arhats (those who have gained such insight as to escape the cycle of rebirth). They became the first members of the Buddhist monastic order known as the sangha.

Later Life

For the next 45 years, the Buddha spread his teachings across northeast India, followed by wandering ascetics and laypersons who supported the ascetics. Although many of his followers imitated him in renouncing the life of the householder, most were not so ambitious.

Over the years, many of the renouncers settled into monasteries funded by prominent members of the laity. The Buddha delivered many of his discourses in the monastery of Jetavana in Shravasti, the capital of Kosala, which had been donated to him by the banker Anathapindada.

When Mahamaya’s sister Mahapajapati, who had been his foster mother and became his stepmother, asked to be ordained, the Buddha refused her, perhaps owing to fears about the safety of nuns. But when pressed, he relented, and Mahapajapati became the first bhikkhuni (Buddhist nun). In time, Yashodhara, too, became a bhikkhuni. When Rahula asked for his patrimony, his father ordained him a monk.

However, the Buddha refused to appoint his radically austere cousin Devadatta as his successor. Bitterly aggrieved, Devadatta tried three times to kill him by means of assassins, a boulder, and an elephant, which arrested its charge to bow at his feet. The schism was repaired when the earth sucked Devadatta down into Naraka, or Hell.

Death

In Kushinagara, the Buddha, now around 80 years old, succumbed to a tainted piece of either mushroom or pork.

His chief disciple, Mahakashyapa, ignited the funeral pyre, after which his relics were distributed and enshrined in large mound-like structures called stupas.

According to Buddhist tradition, in the third century BCE, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka gathered the relics from seven of the eight stupas and erected 84,000 stupas to distribute them across India.

Some of Ashoka’s stupas, such as the Great Stupa at Sanchi and the Dhamek Stupa at Sarnath, remain important pilgrimage sites.

Read more in Indian Mythology and Philosophy.