Self-Control

Visual Journaling as a Reflective Practice

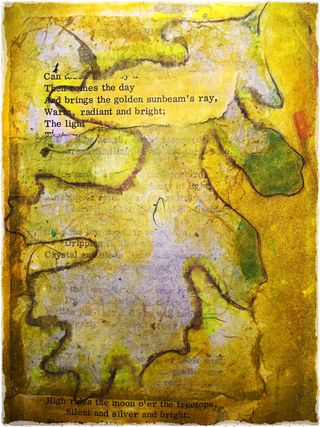

It's the reflection of what is just below the surface.

Posted April 19, 2016

Like many art therapists, I have kept visual journals [also known as art journals] for longer than I can remember. But the visual journaling I do now is quite different from how I approached it a couple of decades ago. As an art student studying at a museum school, tradition dictated that I draw in typical black bound sketch journals almost daily; I carried one or more of these journals with me not only to class, but just about everywhere I went, just in case there was something I wanted to capture with pencil or pastel on paper. These journals became the basis for sketches for larger works like paintings, sculptures and drafts of what seemed like endless creative projects.

Once I started to study art therapy and psychology, my view of visual journaling changed, suddenly becoming less about declaratively recording the external world or prep for formalizing a painting or other artwork. Instead, I redirected my journals toward the inner worlds of imagination and often to what was just below the surface of awareness—an implicit knowing that contains more than what can be put into words. It also became a life-long process of learning through what is historically referred to as a reflective practice; in other words, it became a way of using art making to manifest what is just below the surface in order to deepen meaning and understanding.

This reflective practice leading to implicit knowing from art expression is certainly not new; it has been a core value of art therapy, creative arts therapies and expressive arts therapy for many decades. But in particular, we continue to learn more about the benefits from the relatively simple practice of visual journal, both as a means of self-awareness, but also as a powerful way to promote a sense of health and well-being. In several previous posts, I have explained some of the various reflective practices and approaches involved in visual journaling, from self-regulation to self-care. Here are a few highlights:

From “Doodling Your Way to a More Mindful Life”: "Doodling is not just a way to “think differently;” it’s a way to “feel differently,” too. From emerging studies, we are learning that art expression may actually help individuals reconnect thinking and feeling, thus bridging explicit (narrative) and implicit (sensory) memory. The wonderful thing about doodling is that it is a whole brain activity—spontaneous, at times unconscious, self-soothing, satisfying, exploratory, memory-enhancing, and mindful. In essence, doodling (and drawing and painting and making things in general) can be a self-regulating experience as well as a pleasurable road map of thoughts and ideas."

From “Altered Books and Visual Journaling”: "All art making is in some way about transformation and renewal; altered art empowers the creator to restore what has been lost and make changes to what already exists through symbol and metaphor."

From “Visual Journaling, Self-Regulation and Stress Reduction”: “Perhaps visual journaling and written narratives work in two complementary ways:

1) "Creating an image, even a simple one with colors, line and shapes, expresses the sensory parts of the traumatizing event. It is a way to tangibly convey what words cannot adequately communicate or explain in a logical, linear way.

2) "Writing about the image and the event not only translates experiences into language, but also performs another important healing function. Creating a written narrative may actually begin the process of detaching from intrusive thoughts and putting upsetting feelings (sensory memories) into a chronology. Rather than remaining a disturbing mixture of free-floating emotions, experiences are placed in an objective, historical context.”

From “Visual Journaling as Self-Care”: “While a visual journal is often private experience, remember that if you really want to get the most out of it, an empathetic and reflective witness is important. A helping professional [and of course, an art therapist] can help you deepen narrative work through your images; a visual journaling group that meets regularly to share creative work is another good option. There are online art communities that offer opportunities to connect with others who are exploring visual journaling, too.” [Note: visit this link for a free PDF on visual journaling on my Author's Page]

The practice of visual journaling, with or without the presence of words or verbal narratives, can be a powerful container for life’s more difficult experiences and transitions, a source of mindful moments, and ultimately a method of self-care via the visual language of art. However, never discount the importance of a witness who can facilitate the process of understanding the implicit knowledge within your art journalings. This can be a skilled and sensitive therapist or a community of trusted and supportive individuals engaged in visual journaling as a form of self-exploration and transformation. Ultimately, the implicit knowing of your images do not really have a visual voice unless it is witnessed and honored for the wisdom it contains.

Be well and keep a visual journal handy,

Cathy Malchiodi, PhD

© 2016 Cathy Malchiodi, PhD cathymalchiodi.com | trauma-informedpractice.com

Learn more about visual journaling and expressive arts therapy in a 3-day intensive learning experience on June 22, 23 & 24, 2016 at the Lowry Conference Center, Denver CO; experience visual journaling for self-regulation, meaning-making and self-care and learn the research behind the methods as well as practical approaches and activities to apply in counseling, psychotherapy, health care and education. For more information and registration, see Trauma-Informed Practices and Expressive Arts Therapy Institute current offerings.