Attention

We Need to Think More about Viruses

What if I were to suggest that viruses run this planet? Would you believe me?

Posted November 16, 2018

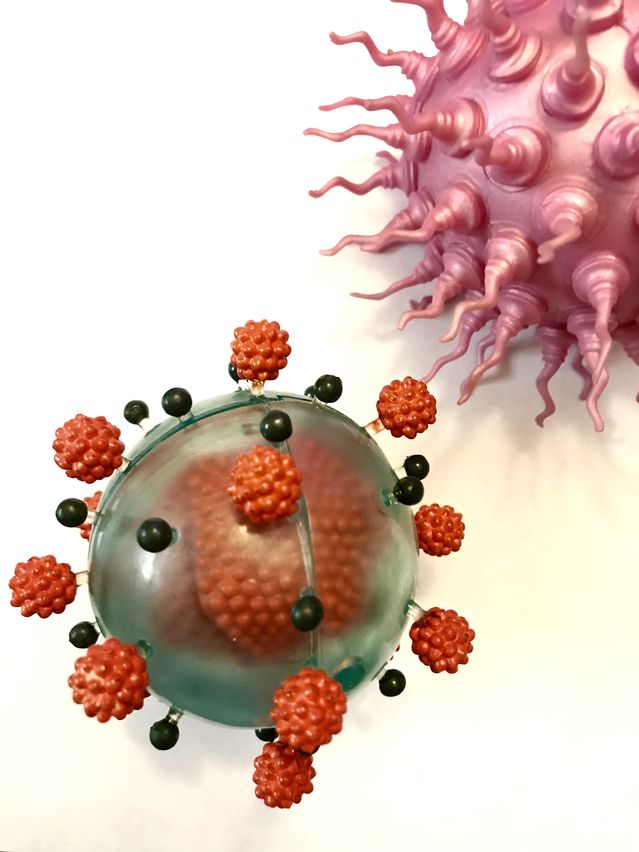

You are a bustling, booming ecosystem that never sleeps. Right now—on the surface of your body, in pores, creases, and folds of skin, and even deep inside of you—live trillions of creatures. Some are just along for the rent-free ride, some help you in crucial ways, and a few may be harming you. Everywhere you go, a unique cloud surrounds you as you shed an organic fog of these beings. Much like the Earth, a planet saturated with abundant and diverse life, you are less of an individual than a conglomerate. Your personal existence, only vaguely outlined by your physical body, is a complex and interdependent coalition of human cells, bacteria, fungi, archaea, and eukaryotes. But even all this is far from a complete picture—for both the Earth and you. Something else is interacting with, influencing, and engineering your ecosystem and all others. It’s viruses—lots and lots of viruses. They profoundly shape your life and the living world around you.

"Viruses are such a powerful and regulating presence in the microbial world, especially in the ocean, that they are now known to be a major influence on global climate."

We all can stand to learn a little more about viruses. These “things” matter far too much to be omitted from anyone’s worldview and even demand inclusion when it comes to our self-perception. I suspect that most people probably imagine a few flu viruses lurking on a doorknob, maybe a couple of cold viruses drifting about the room on puffs of air, and that’s about it. But the reality is that we are constantly swimming within a thick, endless sea of viruses. They are everywhere, always. Though viruses do not qualify as living creatures, I included substantial attention to them in a chapter about life in my book, At Least Know This: Essential Science to Enhance Your Life, because they share such a long and tangled relationship with life. I am awestruck by them. They do so many things that most people are unaware of. For example, viruses are such a powerful and regulating presence in the microbial world, especially in the ocean, that they are now known to be a major influence on global climate.

Their relentless assault on and delicate coexistence with various lifeforms means that viruses direct many of the brooks, eddies, currents, and rivers of evolution. By infecting, changing, and killing life, they have been unintelligent and indifferent directors of natural history for billions of years. One can hardly overstate the significance of this. Without viruses, the natural world we know and depend on today would not—could not—exist in anything close to present form and function. It is even possible that there would never have even been any life here at all if not for viruses. Some 4 billion years ago they may have been precursors to the first cells and served as the critical bridge between nonlife and life.

Viruses are nature’s emotionless and tireless nanobots. Lifeless packets of chemicals they may be, but, like tiny Terminators, they keep coming and coming, hijacking and controlling lifeforms toward their own ends. Their ubiquitous presence, effectiveness, and incomprehensible numbers easily make them one of the most consequential natural forces on Earth. We live in their immense shadow every moment of our lives.

"There are 10 million times more viruses in the ocean than stars in the entire known universe. It's clear that their game plan is working."

Shock and awe are common reactions from people when I share a few basic facts about viruses. For example, did you know that viruses kill approximately half of all marine bacteria in every 24-hour period? Overall, viruses kill some 20 percent of all larger marine life every day. Think about this for a moment: A substantial ratio of multicellular ocean lifeforms (marine plants, mollusks, jellies, arthropods, fish, rays, mammals) don’t live to see the next day because of viruses. The viral infection rate in the ocean is a staggering 1024 per second. (Visualize a 10 with 24 zeros after it) Every day, from moment to moment, the Earth’s largest and most important ecosystem is reshuffled and transformed by viruses. Forget Poseidon, Neptune, and Aquaman, viruses rule the ocean world.

Their diversity is no less stunning. Scientists have identified and named approximately 5,000 different kinds of viruses to date, but many millions of types are confidently estimated to exist currently. If we were to one day declare that viruses meet the definition of life, then viruses would instantly become the most abundant life-form on this planet—by far. A couple of pounds of muck from the seafloor, for example, may contain more than one million different kinds of viruses. Does it impress you that approximately 100 billion humans have ever lived? You can find that many individual viruses in one liter of seawater. Viruses are so numerous that if they were the size of a beetle or medium-sized spider, they would cover the entire world with a layer that is many miles thick. There are 10 million times more viruses in the ocean than stars in the entire known universe! It's clear that their game plan is working.

Viruses are extremely small, of course. An individual virus weighs virtually nothing. Their combined weight, however, can be astonishing. For example, all ocean viruses together exceed the weight of 75 million blue whales. Perhaps even more surprising, if you were to place all marine viruses end-to-end in a straight line (assuming an average length of 100 nanometers), they would reach out 10 million light years, stretching beyond the nearest 60 galaxies. And this doesn’t even include Earth’s land and airborne viruses.

Humans and viruses share such an ancient and tangled relationship that I sometimes hesitate to refer to viruses as “them.” We may view viruses as foreign trespassers, but the evidence indicates something very different. Individual viruses are not only on your skin and inside your body. Their footsteps are all over your genome, too. Some 5 to 8 percent of the genetic material found in the human genome came from viruses. Yes, your personal genetic code includes the unmistakable evidence of these ancient invaders who stayed. It’s a fascinating fact to contemplate; we all contain significant remains from viral foundations.

Evidence clearly and strongly suggests that viruses have been our original and constant companions across vast stretches of time. I can imagine how strange and troubling this must feel to those who are already bothered by our close kinship to apes (98.7 percent shared DNA with bonobos). And now we have to hear about viral cousins, too? Scoffing followed by blanket rejection may be tempting here. But keep in mind that a big part of being a mature and honest thinker is accepting reality, as evidence reveals it, no matter how weird or unexpected it may turn out to be. Try to remember that reality cared nothing about our sensitivities. Done correctly, science never caters to our prejudices, hopes or assumptions. That’s why science works and has been more consistently productive and reliable than anything else we have by far.

Given their importance, is it not odd that viruses continue to be ignored or at best poorly understood by the public? After all, one would think that having these bizarre things all over us and inside of us would motivate everyone to know as much about them as possible. One cannot claim to know humankind or life in general without some appropriate understanding of viruses. The unfortunate reality, however, is that most people give little thought to viruses apart from fear of illness and disease. And even this common concern is often muddled and inaccurate.

"Forty-five percent of American adults don’t understand that antibiotics work on some species of bacteria but not on viruses."

In 2016 the National Science Foundation published the results of their international study on general science knowledge and among its findings was the revelation that many people seem to believe viruses, bacteria, archaea, and other microbes are all the same thing, essentially just “germs.” For example, nearly half of American adults, 45 percent, don’t even know that antibiotics work on some species of bacteria but not on viruses. Fifty-four percent of Europeans don’t know this, while 72 percent of Japanese people and 82 percent of Russians don’t. For the record, viruses and bacteria are nothing alike. Bacteria are practically our twin siblings compared to viruses.

The story of the virus is long, complex, and far from complete, of course. Given how tough and weird they are, it is a reasonable possibility that viruses may have originated somewhere other than Earth. That aside, we have more than enough evidence-based knowledge down here on Earth to understand that they are a powerful presence. Even the noise and sparkle of our extravagant civilization dims a bit in the glaring light of what viruses have helped to build around us and within us. The more one learns about them, the more one tends to wonder if our species is a mere bystander here on Planet Virus. This much is certain: If we wish to understand ourselves and all our living neighbors better, we must know viruses.

References

Guy P. Harrison, At Least Know This: Essential Science to Enhance Your Life, Prometheus Books, 2018.

University of California Berkeley, “From Prokaryotes to Eukaryotes,” Understanding Evolution, https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/_0/ endosymbiosis_03 (accessed February 15, 2018).

Ron Sender, Shai Fuchs, and Ron Milo, “Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body,” PLOS, August 19, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533 (accessed September 30, 2017).

John Travis, “All the World’s a Phage,” Science News, July 7, 2003, https://www.sciencenews.org/article/all-worlds-phage

Erin Allday, “100 Trillion Good Bacteria Call Human Body Home,” SFGate, July 5, 2012, http://www.sfgate.com/health/article/100-trillion-good -bacteria-call-human-body-home-3683153.php (accessed October 2, 2017).

David Enard, Le Cai, Carina Gwennap, and Dmitri A Petrov, “Viruses Are a Dominant Driver of Protein Adaptation in Mammals,” eLife 5 (2016), https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.12469 (accessed November 3, 2017).

Karin Moelling, “Are Viruses Our Oldest Ancestors?” EMBO Reports 13, no. 12 (December 2012): 1033, https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2012.173 (accessed March 15, 2018); P. Forterre, “The Origin of Viruses and Their Possible Roles in Major Evolutionary Transitions,” Virus Research 117, no. 1 (April 2006): 5–16, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.010 (accessed March 15, 2018).

Emidio Scarpellini, Gianluca Ianirob, et al., “The Human Gut Microbiota and Virome: Potential Therapeutic Implications,” Digestive and Liver Disease 47, no. 12 (December 2015): 1007–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. dld.2015.07.008 (accessed March 15, 2018).

R. Belshaw, V. Pereira, A. Katzourakis, et al., “Long-Term Reinfection of the Human Genome by Endogenous Retroviruses,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, no. 14 (April 2004): 4894–99, https:// doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0307800101 (accessed November 3, 2017).

Julia Halo Wildschutte, Zachary H. Williams, Meagan Montesion, Ravi P. Subramanian, Jeffrey M. Kidd, and John M. Coffin, “Discovery of Unfixed Endo genous Retrovirus Insertions in Diverse Human Populations,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, no. 16 (April 19, 2016), https://doi .org/10.1073/pnas.1602336113 (accessed November 3, 2017).

E. B. Chuong, N. C. Elde, and C. Feschotte, “Regulatory Evolution of Innate Immunity through Co-Option of Endogenous Retroviruses,” Science 351, no. 6277 (2016): 1083, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5497 (accessed November 3, 2017).

David Enard, Le Cai, et al., “Viruses Are a Dominant Driver of Protein Adaptation in Mammals,” eLife 5 (2016), https://elifesciences.org/ articles/12469 (accessed January 18, 2018). 31. Carl Zimmer, A Planet of Viruses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011)

Curtis A. Suttle, “Viruses: Unlocking the Greatest Biodiversity on Earth,” Genome 56 (2013), doi.org/10.1139/gen-2013-0152 (accessed March 21, 2018).

Curtis A. Suttle, “Viruses in the Sea,” Nature 437, September 15, 2005, pp. 356–61, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04160 (accessed March 21, 2018).

David Enard, Le Cai, et al., “Viruses Are a Dominant Driver of Protein Adaptation in Mammals,” eLife 5 (2016), https://elifesciences.org/ articles/12469 (accessed January 18, 2018).

Carl Zimmer, A Planet of Viruses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Jessica McDonald, “Ocean Viruses May Have Impact on Earth’s Climate,” Science, June 17, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag0620 (accessed March 21, 2018).

R. Belshaw, V. Pereira, A. Katzourakis, et al., “Long-Term Reinfection of the Human Genome by Endogenous Retroviruses,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, no. 14 (April 2004): 4894–99, https://doi .org/10.1073/pnas.0307800101 (accessed November 3, 2017).

Arshan Nasir, Kyung Mo Kim, and Gustavo Caetano-Anollés, “Giant Viruses Coexisted with the Cellular Ancestors and Represent a Distinct Supergroup along with Superkingdoms Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya,” BMC Evolutionary Biology 12, no. 1 (2012): 156, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471 -2148-12-156.

Arshan Nasir and Gustavo Caetano-Anollés, “A Phylogenomic Data-Driven Exploration of Viral Origins and Evolution,” Science Advances 1, no. 8 (September 2015): e1500527, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500527.

National Science Foundation, “Public Knowledge about S & T,” Science and Engineering Indicators 2016 (Washington, DC: National Science Board, 2016), https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsb20161/#/report/chapter-7/ public-knowledge-about-s-t (accessed November 9, 2017).

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, “Study Adds to Evidence That Viruses Are Alive,” ScienceDaily, September 25, 2015, www.sciencedaily.com/ releases/2015/09/150925142658.htm (accessed December 29, 2017).

Carl Zimmer, “Ancient Viruses Are Buried in Your DNA,” New York Times, October 4, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/04/science/ancient -viruses-dna-genome.html (accessed October 4, 2017).

James F. Meadow et al., “Humans Differ in Their Personal Microbial Cloud,” PeerJ 3 (2015): e1258, PMC, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC4582947/ (accessed December 30, 2017).

Rasnik K. Singh, Hsin-Wen Chang, et al., “Influence of Diet on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Human Health,” Journal of Translational Medicine 15, no. 1 (April 8, 2017): 73, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967 -017-1175-y (accessed January 17, 2018).

“Your Microbes, Your Health,” Science 342, no. 6165 (December 20, 2013): 1440–41, https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.342.6165.1440-b (accessed January 17, 2018).