Certainty Is a Psychological Trap and It's Time to Escape

The willingness to actually listen to others and to display your ignorance in a world full of know-it-alls is a bold move that now has a name—intellectual humility. It’s not only a developable skill, but it could just end the culture wars.

By Bruce Grierson published July 5, 2023 - last reviewed on July 21, 2023

In June of 2011, major league pitcher Wade LeBlanc had bottomed out. Having bounced around the league, slowly eroding his early promise, he was back playing with the club that had drafted him, the San Diego Padres. The morning after a particularly bad outing, he hailed a taxi for the airport; he was being sent down to the farm club.

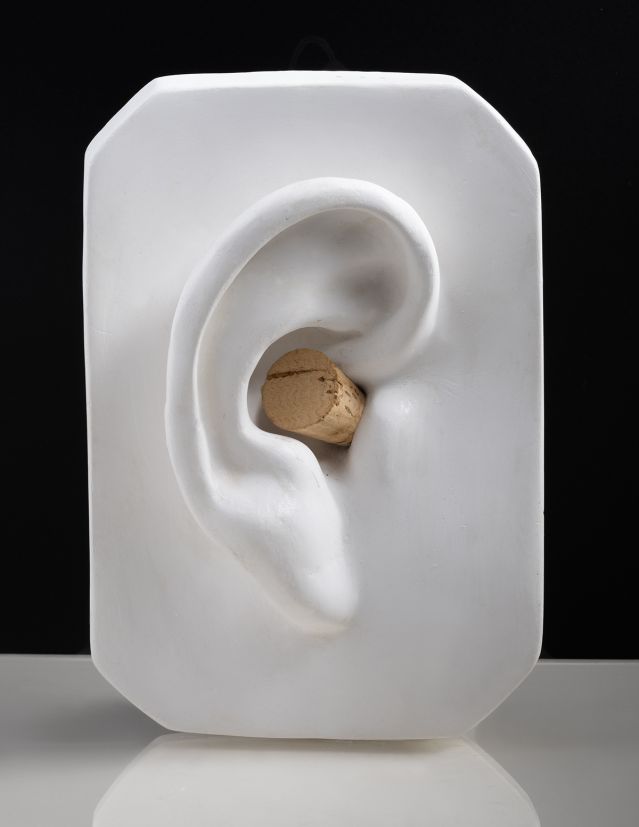

The cabbie had watched the previous night’s game, and he couldn’t resist offering a few pointers. “You know, you’ve got some good stuff,” he told LeBlanc, “but I think there are some things you should think about trying. Maybe like going over your head in the windup.” LeBlanc might have been forgiven for putting his ear buds in at that moment. But he sat there and listened.

When he reported for duty in Tucson with the Padres’ minor-league affiliate team, LeBlanc told the pitching coach that there was something he wanted to try. What if he brought his hands over his head in the delivery? Astonishingly, it worked. He found he had more control. In his next start he deployed the technique and pitched lights-out, allowing one run over seven innings, with no walks. He incorporated the cabbie’s tip into his technique for the rest of his career.

Psychologist Daryl Van Tongeren is less surprised at the result than most. “Whomever you meet, it’s a good idea to assume there is something to be learned from them,” he says. An associate professor at Hope College in Michigan, Van Tongeren is a leading voice in a subdiscipline of psychology that is emerging at the precise moment in cultural life when it is desperately needed— intellectual humility (IH).

With roots in almost every major philosophical and religious tradition, IH occupies an intertidal zone of knowledge somewhere between the Bleedin’ Obvious and the Secret of Life. “Globally right now there’s a rise in the opposite of IH—intellectual arrogance,” which make us privilege our own positions and stubbornly refuse to entertain competing viewpoints, says Michael Patrick Lynch, a philosopher at the University of Connecticut and the author of Know-It-All Society: Truth and Arrogance in Political Culture.

“Democracies,” he maintains, “have a special interest in protecting and promoting the pursuit of truth.” But the contemporary cultural machinery is geared to chase folks out of the middle ground or push experts in one area out of their lane, leading them to confidently pronounce on matters they have no business banging on about. Call it cognitive narcissism. Curious, collaborative inquiry has been abandoned for the brute force of unilateral persuasion. Intellectual humility, instead, courts the kind of nuance that’s often found in the middle ground.

It also contains a strong element of respect: “I respect you enough to engage with your position, and together we commit to search for truth,” says Rick Hoyle, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. The brass ring may be what philosopher Agnes Callard calls Socratic humility, when we come to crave other people’s wisdom—wisdom we ourselves don’t have. The impulse is generous. “You don’t go into a conversation expecting to persuade any more than you expect to be persuaded,” Callard writes. Not only are you open to being persuaded, you actually hunger for it.

Ilana Redstone, a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, has her own term for intellectual arrogance—the certainty trap, which blocks our path to seeing things clearly and getting along. “The certainty trap tells us that there are two possibilities for an opinion we disagree with: ignorance and hateful motives,” she writes. But there’s a third possibility we fail to consider: Our opponent might have principled reasons for their position. “When we refuse to hear or recognize the reasons, we can’t communicate.”

According to Mark Leary, an emeritus professor of psychology at Duke, intellectual humility is “the degree to which one accepts that they could be wrong”—and that someone who’s challenging their position could be right, or at least more right than they’re giving them credit for. No one, but no one, says Leary, has a full claim on the truth. The corollary of that fact: The more diverse perspectives we entertain, the smaller our blind spots and the wiser our decision-making will generally be.

Leary and his colleagues have looked for factors and traits that might incline someone to be intellectually humble. Does political persuasion matter? It seems not; neither liberals nor conservatives appear, as a group, to be more intellectually humble. Gender? No. Nor does a high level of education correlate with intellectual humility. If anything, the reverse may be true.

Do people with IH make more thoughtful decisions? Do they have stronger connections with their friends and partners? Are they happier than others? (Early returns say yes, yes, and yes.)

From the emerging data, here are eight ideas about fostering intellectual humility.

1. You can’t actually know when you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Some of the major discoveries in behavioral science of the last 20 years are our cognitive blind spots and just how big they are. We think we know more than we do. Our intuitions about what we’re right or wrong about are faulty. “Wrong never feels wrong in the moment,” writes Kathryn Schultz, Pulitzer Prize–winning essayist and pioneering “wrongologist.” What does it feel like? “It feels like being right. We know what it feels like to have been wrong in the past, perhaps just seconds ago, but not what it feels like to be wrong in the present. Because the instant we realize that what we believe is wrong, we no longer believe it.”

One major culprit is the overconfidence bias that afflicts most people—the tendency to overestimate our abilities, knowledge, and beliefs. Most of the time we are simply way more certain than we should be. “Think about all of the disagreements you have with other people—from minor ones about relatively unimportant issues to major ones about important matters,” Leary asked a sample of adults. “Now I want you to estimate how often—what percentage of the time—you think you’re the one who is correct.” The average answer: 82 percent of the time.

Unjustifiable confidence is not just rampant, it can be dangerous. “No problem in judgment and decision-making is more potentially catastrophic than overconfidence,” insists Wesleyan social psychologist Scott Plous. Its consequences include the Chernobyl disaster, the sinking of the Titanic, the Challenger and Columbia space shuttle disasters, and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, among many others.

Given the unreliability of our memories and our predictions, the fallibility of our perceptions, and the dubiousness of our confidence that we look mahvelous in this haircut, how could we lead with anything but abject intellectual humility? Maybe the patron saint of IH should be George Costanza, and his solution should be our default: Whatever it occurs to us to do, assume we’re wrong and do the opposite.

2. The road to intellectual humility is paved with curiosity.

Leary’s research revealed a strong correlation: Curious people tend to be intellectually humble.

Our human desire for certainty—understandable if also sometimes unhelpful—is tempered by curiosity. “Certainty is about being right,” says George Mason University psychologist Todd Kashdan, whereas curiosity is about exploration. And that is an instinct almost beyond right or wrong. It’s simply data collection—a definitively intellectually humble pursuit. Curious people ask a lot of questions—and that is a sneaky superpower in a culture obsessed with answers.

Social curiosity, it turns out, is a particularly potent attribute—an interest in other people’s behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. Unlike extraversion, the tendency to socialize with others, social curiosity is motivated by the desire to understand what makes people tick. Social information is gathered by directly talking to people. Besides being more agreeable and less lonely, Kashdan has found, socially curious people are also more open-minded than others. Psychologists Tenelle Porter, of the University of California Davis, and Karina Schumann, of the University of Pittsburgh, have found that people high in IH are even interested in understanding the reasons that people disagree with them.

The application of curiosity softens your defenses against hostile pushback. Tufts University psychologist Jamshed Bharucha calls this a “golden rule of cross-group understanding.” When you’re genuinely curious, it’s harder to be judgmental, and when you’re judgmental, it’s harder to be genuinely curious.

Kids are naturally curious, but sometimes it takes deliberate commitment to remain highly curious as an adult. Curiosity may be a particularly sharp tool in situations of conflict. “When someone starts to launch an assault on your world view,” notes Adam Grant, “it’s not that difficult to ask, ‘How did you arrive at that view? I’m really curious.” Suddenly, they no longer see you as a preacher or a prosecutor or a politician. You are just a curious human. And they let down their guard and start to trust you enough to spill their guts, unguarded.

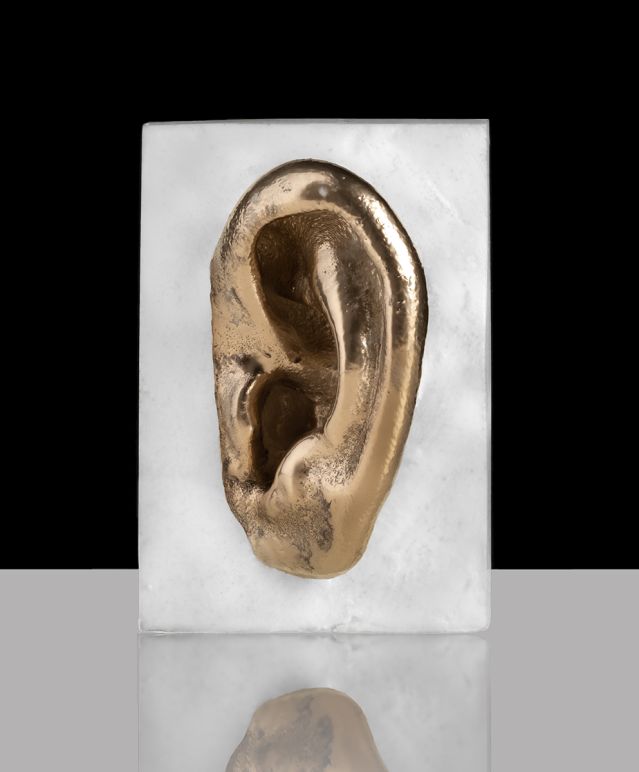

Of course, it’s not enough to be privately curious. You have to demonstrate that curiosity. What percent of people, at the end of a conversation, say they felt “heard”? A study recently published in Frontiers in Science answered the question: 5 percent. Only in one in 20 conversations do we feel genuinely heard at the end. We are really not very good at listening to each other.

3. Not everything should be up for humble reconsideration.

For many of us, there are certain domains in which we’re willing to be intellectually humble, open to the possibility that we may be wrong. But there are also areas we simply draw a line around. It could be anything from the case for gun control or the effectiveness of vaccines to the existence of God.

“Each of us is intellectually humble about some topics but dogmatic about others,” Leary says. That’s normal and healthy; we all need a few no-go zones. What has happened, however, is that, for many of us, our no-go zones are proliferating. As polarized discourse becomes a cultural reflex, there’s a kind of scope-creep in what we are not willing to entertain.

Part of the work of intellectual humility, then, is to try to decrease our “latitude of rejection,” as it’s sometimes put. To periodically check in with ourselves about what’s impermissible speech—or even thought—and ask why we drew a boundary there. We should probably keep our number of no-go zones to a small handful of genuinely inviolable offenses: Human trafficking or child abuse, for sure, hold the line. But maybe not Beatles vs. Stones.

4. A conflict-resolution tool? Maybe, maybe not.

As we toy with intellectual humility as a tool to bridge conflict, it’s important to remember that conflict in itself is not the problem. Ian Leslie, the British journalist and author of Conflicted, has a good line: “The opposite of conflict isn’t harmony—it’s apathy.” People should disagree. A population that’s all in line is not a healthy population. This is about how we disagree and learn to disagree well.

The commentator Ezra Klein has said that when he writes an article he ends up more convinced of his position, but when he contributes to a podcast he ends up less convinced. The difference is this: In the first act, he’s alone; in the second, he’s actually mixing it up with another human.

5. Proximity helps.

A large body of research suggests we often have wild misconceptions about our ideological opponents, which amplifies conflict. Every hard progressive would do well to imagine how some of their messages are landing on the ears of a random Boomer conservative from the heartland. What they hear: Revolution’s a comin’, and you and your family are on the wrong end of it, Bud. They aren’t likely to lean over the fence and say, “Tell me more.” What can help—maybe the only thing that can help—is stripping away the propaganda layer by getting folks together, in real life, where each may realize that the other is not the twisted cartoon character they imagined.

Not long ago, Monica Guzman, a senior fellow at the New York–based nonprofit Braver Angels, recruited volunteers from her native King County, Washington (mostly Seattleites), to take a bus ride down the I-5 to meet some of their political antipodes in Sherman County, Oregon. The two counties voted exactly opposite in the last presidential election. Braver Angels is dedicated to political depolarization, and Guzman was interested here in the power of genuine curiosity.

She coaxed her subjects to ask themselves this question: If people are voting opposite me, are they feeling opposite me on the issues that matter to me? Or is there something I’m missing?

There was no self-righteousness, just an attempt to understand, and folks listened to their opposite numbers. The visitors discovered that many of their hosts voted for Trump for reasons they hadn’t even considered. Not the environment. Not LGBTQ rights. (Many had no quarrel with those issues.) Rather, a farmer may have worried about losing control of his land because of the Waters of the United States legislation, which Trump was fighting to have removed.

“We assume people oppose what we support because they hate what we love,” Guzman says. “But that may not be true at all.” One participant told Guzman that being there in person changed everything. “I was surprised by the complexity of the stories I heard,” she said. They made sense to her in a way that the online stories she’d read could not.

6. There is such a thing as too much IH.

Clearly, one can have too little IH. But one can also have too much. If you think of intellectual humility as a continuum, with arrogance on one end and abject servility the other, healthy IH occupies the sweet middle. The key is to take the appropriate amount of space as befits your level of knowledge in this domain. Appropriate. Not less.

“People who shrink in a situation—that’s not intellectual humility,” Van Tongeren, says. “I wouldn’t want my brain surgeon to say, ‘I dunno, Daryl, what do you think I should do?’” The question to ask yourself in a given situation is: Am I the right size here? “I think of it as calibrating your certainty to the level of your knowledge, while still recognizing that you could be wrong,” Leary notes. “You’re asking yourself: Given everything I do and do not know about this topic, what’s the probability I’m correct?”

Beware, though, of false humility, which is actually a kind of stealth arrogance. “Some people will be, like, OK, I admit I could be wrong,” says Lynch, “and my own genius will later discover other things I could be wrong about.”

7. IH is something humans will always have that even the smartest machine learning will not.

As the chatbots encroach on our most intimate precincts, here’s one place that they will likely never reach. AI can argue a position with an assurance that borders on annoying. What it can’t do is humility.

Machine learning “does not have the capacity to question its own capacity,” says Emily Tucker, a human rights lawyer and executive director of the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown University. While chatbots appear to be thinking deeply, what they’re really doing is just pattern-matching, with no sensitivity to whether the correlations they detect are meaningful. And they certainly can’t consider that some of their answers might prove wrong in ways that haven’t occurred to them yet. “That is a faculty that’s essentially unrepresentable mathematically,” Tucker says.

8. People arrive at truth collaboratively.

In their book, The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone, cognitive psychologists Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach argue that individual intelligence is more limited than we recognize and we are all basically sharing our class notes. It would be silly not to. There’s just too much material in the syllabus; we’d be crazy not to distribute the work.

When we divide the cognitive labor, we’re undertaking intellectual humility as a communal enterprise. Kant would tip his cap. If everyone learned to see through the lens of contingency, then that would be the end of dogma.

The more we know, the more we realize how much we don’t know. We peer from the crater rim of the known unknowns into the vast caldera of the unknown unknowns.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s debut novel, Player Piano, a character makes a pronouncement that could be the calling card for the whole field: “We should recognize that while we may be able to offer something useful, we’re also flawed actors, hampered by our own lack of knowledge. Let’s build opinions like sandcastles, with curiosity but no great attachment.” Because the next tide could take them out.

How to Cultivate Intellectual Humility

Because accepting our fallibility is so hard—in a sense we’re working against an almost primal impulse to be right—the enterprise of becoming more intellectu-

ally humble has to effectively be a training regimen, deliberate and systematic. But it can be done. Here are three strategies that have been proven to work.

Put your money where your mouth is.

Immanuel Kant claimed that if everyone were forced to put a wager on their casually floated opinions, they’d back off their certainty. Modern behavioral science has borne out the principle generally: One way to boost intellectual humility is to raise the stakes.

That’s one reason University of Pennsylvania professor Philip Tetlock decided to create forecasting tournaments where folks try, very publicly, to predict the outcome of unfolding political and social events. When people are forced to accountably make a specific prediction, they’re likely to take a more moderate stance than they otherwise would. There’s “the cognitive dissonance thing,” Tetlock explains. “Secondly, the mere fact that you know that your prediction is going on the record makes you more self-critical.”

Hunt for the smartest adversary you can find.

To peek into our blind spots and push through our biases, it sometimes helps to have an accomplice. Before she became a columnist for The New York Times, Columbia University sociologist Zeynep Tufekci invited her most formidable critics to take her down in her own newsletter. This is the steel-man strategy (vs. the more familiar straw-man strategy, where you reduce your foe’s argument to its flimsiest parts and blow them away).

“Explain it to me as if I were a 5-year-old.”

You think you know how a toilet works? A zipper? Explain it. Pressed to describe the workings of familiar objects, most of us find our shaky command of the details nakedly exposed—what psychologists call the “illusion of explanatory depth.” “We begin to see that the whole damn thing is far more complicated than we thought,” says Leary.

How Sure Are You of That?

On a scale of 1 to 5, would you say:

____ I question my own opinions, positions, and viewpoints because they could be wrong.

____ I reconsider my opinions when presented with new evidence.

____ I recognize the value of opinions that are different from my own.

____ I accept that my beliefs and attitudes may be wrong.

____ In the face of conflicting evidence, I am open to changing my opinions.

____ I like finding out new information that differs from what I already think is true.

Scores can potentially range from 6 to 30. Leary and colleagues find that the average score is 22.2. Scores below 20 fall in the lower 25% in intellectual humility. Scores above 25 fall in the upper 25% .

Intellectual Humility Scale Courtesy of Mark R. Leary, Kate J. Diebels, Erin K. Davisson, Katrina P. Jongman-Sereno, Jennifer C. Isherwood, Kaitlin T. Raimi, Samantha A. Deffler, and Rick H. Hoyle.

Bruce Grierson, a writer in Vancouver, has won the Canadian National Magazine Award five times. His work appears in many publications around the globe.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of this issue.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Faces Portrait/Shutterstock