My Brother, The Unabomber

David Kaczynski always sensed that there was something unusual about his beloved older brother, Ted. The truth was far worse than he could have ever imagined.

By David Kaczynski published January 5, 2016 - last reviewed on June 10, 2016

In the late summer of 1995, my wife, Linda, put her hand on my knee as she sat me down for a serious talk.

"David," she asked, "has it ever occurred to you, even as a remote possibility, that your brother might be the Unabomber?"

At the time, the hunt for the so-called Unabomber was the longest-running and most expensive criminal investigation in the history of the FBI. Over 17 years, this shadowy criminal had mailed, or placed in public areas, 16 explosive devices that had claimed the lives of three people and injured dozens more. In the previous year alone, he had killed two people—a forestry industry lobbyist and an advertising executive. The Los Angeles airport had recently been shut down after it received a threatening letter from him. Media reports announced that he had sent a 78-page manifesto to The New York Times and The Washington Post with demands that it be published—or else more bombs would be mailed to unsuspecting victims.

"What?" I said, unsure if I'd heard her right. I felt a mixture of consternation and defensiveness. This was my brother she was talking about! I knew that Ted was plagued with painful emotions. I'd worried about him for years and had many unanswered questions about his estrangement from our family. But it never occurred to me that he could be capable of violence.

The manifesto had not been published, but Linda pointed out that it was being described by media sources as a critique of modern technology, and she knew that my brother had an obsession with the negative effects of technology. She also mentioned that one of the Unabomber's explosives had been placed at the University of California, Berkeley, where Ted was once a mathematics professor.

"That was 30 years ago," I countered. "Berkeley is a hotbed for radicals. Besides, Ted hates to travel, and he has no money."

"But we loaned him money, didn't we?" she said. I didn't like the way the conversation was developing. The mind can patch together evidence to support any idea, I thought.

At the time, Linda and I were both deeply involved in our careers. Linda was a tenured philosophy professor at a liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York, where we lived. With a background as a social worker, I was the assistant director of a shelter for runaway and homeless youth in nearby Albany. The kids I worked with often faced severe challenges that dimmed their prospects for success, and I felt good about helping them and their families grapple with their problems, oblivious to the crisis building in my own family.

A month after Linda approached me with her suspicion, the Unabomber's manifesto was published in The Washington Post. I felt certain that after reading it I would be able to say that it wasn't the work of my brother. I'd had years of extensive correspondence with Ted, after all. I knew how he thought and how he wrote.

Reading the manifesto on a computer at our local library, I was immobilized by the time I finished the first paragraph. The tone of the opening lines was hauntingly similar to that of Ted's letters condemning our parents, only here the indictment was vastly expanded. On the surface, the phraseology was calm and intellectual, but it barely concealed the author's rage. As much as I wanted to, I couldn't absolutely deny that it might be my brother's writing.

"The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race," the manifesto read. "They have greatly increased the life expectancy of those of us who live in 'advanced' countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering...and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world."

Over the next two months, Linda and I pored over the manifesto repeatedly and made careful comparisons with piles of letters Ted had sent to me over the years from his one-room cabin in rural Montana. Sometimes I thought I was projecting my worry, seeing what I most feared. At other times, I thought I might be in denial, unable to grasp the painful truth because I lacked the wherewithal to deal with it. Each day, the pendulum of belief swung between doubt and its opposite.

The day came when I finally acknowledged that Linda might be right. "I think there's a 50-50 chance that Ted wrote the manifesto," I told her. She knew what it cost me to say those words. Now what we were we going to do? Continue thinking and talking while my brother was, perhaps, constructing another bomb?

The options we faced were not very appealing. Notifying the FBI, I thought, could be disastrous. I reminded Linda of the agency's attempts to make arrests at Waco and Ruby Ridge, which resulted in many deaths. I reminded her of Ted's paranoia and emotional fragility. Suppose the FBI sent an agent to his cabin to ask questions—in Ted's paranoid state, he might panic and lash out or go off and hurt himself, even if he were completely innocent. And if he weren't innocent, what if my notification ultimately led to his death by execution? What would it be like to go through the rest of my life with my brother's blood on my hands?

Furthermore, what would this do to my mother? She was a 79-year-old widow who had worried for years about Ted's emotional problems, isolation, and estrangement from the family. I knew her worst fears about Ted didn't come close to the awful suspicion that Linda and I were struggling with. She would be emotionally crushed. She might even have a fatal stroke or heart attack. I couldn't imagine how I would comfort her. Her wounds would never, ever heal.

The conflict between our moral obligation and my love for Ted could not be reconciled. A decision could not be made without sacrificing one for the other. We wrestled with these questions by day and by nightfall felt even more confused and upset. If Ted was the Unabomber, it meant he was responsible for wanton, cruel attacks on innocent people, yet I couldn't uncover any memories that revealed such deep-seated evil in him. As Linda and I lay awake in our bed, side by side in the darkness, I wondered if I'd ever really known my brother.

TROUBLE BREWS

I don't remember a time when I wasn't aware that my brother was "special," a tricky word that can mean either above or below average, or completely off the scale. Ted was special because he was so intelligent. In school he skipped two grades, and he garnered a genius-level IQ score of 165. In the Kaczynski family, intelligence carried high value.

Despite our age difference—Ted was seven and a half years older—we grew up deeply bonded. He was consistently kind to me and went out of his way to offer help and encouragement. In return, he won my admiration and deep affection. As a young child beginning to gauge social perceptions, I thought of him as smart, independent, and principled. I wanted to be like him. But even though I placed him on a pedestal, wanting to emulate his intellectual accomplishments, there was another part of me that sensed that he was not completely OK. I was 7 or 8 when I first approached Mom with the question, "What's wrong with Teddy?"

"What do you mean, David?" she said. "There's nothing wrong with your brother."

"I mean, he doesn't have any friends. It seems like he doesn't like people."

Mom and I sat down on the couch and she told me about my brother's early life. "When Teddy was just nine months old, he had to go to the hospital because of a rash that covered his little body," she told me. "In those days, hospitals wouldn't let parents stay with a sick baby, and we were allowed to visit him only every other day for a couple of hours. Your brother screamed in terror when I had to hand him over to the nurse and she took him away to another room. He was terribly afraid, and he thought Dad and I had abandoned him to cruel strangers. He probably thought we didn't love him anymore and that we would never come back to bring him home again. The hurt never went away completely." In her attempt to understand her firstborn's behavior and temperament, this story seemed to furnish a reasonable explanation.

At the time, I never questioned that the four members of our family were connected through unbreakable bonds of love. Only as I neared adolescence did I realize that Ted didn't return our parents' love—at least not in ways that were easy to recognize or receive. When hugged as a child, he squirmed instead of hugging back. In adolescence, he stiffened when embraced by our mother. It was as if his way of relating followed a different set of rules. Unable to fathom Ted's internal physics, Dad eventually gave up, whereas Mom preferred to believe that her son's sensitive inner self was normal and loving, only hard to reach because of his hospital experience.

Ted left for Harvard when he was 16. Our family album holds a color picture of him and me standing outside our home, together gripping the handle of Ted's one bulky suitcase. He looks handsome and serenely self-confident. I am the admiring younger brother, vicariously enjoying his triumphant departure to a future without limits.

He graduated from Harvard with a degree in mathematics and a teaching fellowship at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. There, he published original mathematical research and won a prize for the university's best Ph.D. thesis in mathematics. He was a rising academic star. After earning his doctoral degree at Michigan, he was appointed assistant professor of mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley.

By then, Ted and I had come to relate more as adult peers than as big and little brother. I'd come to enjoy a feeling of greater equality with him, and I was pleased that he acknowledged me and encouraged my independence. But I also felt myself gradually drifting apart from him. While I still admired his intelligence and strong character, he increasingly expressed a level of negativity and hopelessness that didn't resonate with my essential optimism.

In 1969, he abruptly quit his professor's job and announced to our family that he thought technological development was threatening humanity and the environment. His overriding concern, he said, was the erosion of human freedom and autonomy brought on by technology. In fact, he had grown so concerned that he was determined to remove himself personally from industrial society as much as he could. To this end, he would attempt to live in the wilderness as primitive peoples had done for most of human history.

His alienation continued with blistering letters to our parents that started arriving in the mid-1970s. The gist was that he had been unhappy all his life because they had never truly loved him. He claimed that they had pushed him academically to feed their own egos and that they'd never taught him appropriate social skills because they didn't care about his happiness. The letters were not an invitation to talk but an indictment filled with highly dramatized and, in my view, distorted memories.

Mom and Dad experienced the full force of their elder son's rejection in the form of a 23-page letter that arrived around 1977. His hand seeming to shake with rage as he wrote, Ted wove details from his childhood into an immense, dark tapestry of rejection and humiliation. In one place he noted that Mom once yelled at him for throwing his dirty socks under the bed. She should have known, Ted fumed, that tossing dirty socks under a bed was normal behavior for an adolescent boy. The letter read like a three-year-old's tantrum translated into an adult's analytical language. What I found most disturbing was that it seemed calculated to inflict pain. As much as I tried to normalize Ted's behavior, a voice in the back of my mind told me that something had shifted dramatically in his world—a world so much stranger and darker than I had previously guessed.

For years after he cut off relations with our parents, I still corresponded regularly with Ted. I soon realized that I couldn't soften his feelings toward Mom and Dad and that I needed to tread carefully around that topic if I wanted to maintain a relationship with him. I couldn't imagine my life without Ted's presence, nor could I imagine him completely isolated from human contact, and I seemed to be the only person he allowed into his increasingly narrow world.

Meanwhile, Mom's handwringing and soul-searching never stopped. Whenever I spoke with her, she asked for news about Ted. She was always worrying about him, looking for answers and ways to help him. On one of my visits home, she handed me a copy of This Stranger, My Son by Louise Wilson, a book that tells the story of a mother trying to understand and get help for her mentally ill son, and asked me to read it. In painful detail, Wilson describes her son's distorted perceptions of the world, his psychiatrists' inclination to blame the parents—particularly the mother—her own sense of guilt and shame, the unavailability of effective help, her endless worry over her son's problems and uncertain future, and the disintegration of his peace and happiness. I asked Mom if she wanted me to read it because it reminded her of Ted.

She was quiet for a moment. "Well, parts of it really did make me think of your brother," she said with concern in her eyes. "Not that I think Ted is schizophrenic. But maybe he has tendencies in that direction."

BLINDERS OFF

In March 1996, I climbed the stairs to Mom's second-floor apartment. When she opened the door, her smile quickly turned to a look of dismay.

"David, you look terrible!" she said. "Is something wrong? Tell me, what is it?"

Perhaps it was the years of nagging worry, or else it was a mother's radar-like intuition, but she immediately homed in on her elder son: "Is it Ted? Oh, my God! Did something happen to Ted?" Panic rose in her voice. "Oh, David, tell me, please!"

"As far as I know, Ted's in good health," I said. "But I do have something troubling to discuss with you."

I paced the floor back and forth, searching for some painless way to deliver my awful news.

"Mom, have you ever read any newspaper articles about the Unabomber?"

I saw her tense up, although as it turned out, she had little more than a passing knowledge of the Unabomber's activities. I gave her a quick summary of his course of bombings and terror, and talked about the places the Unabomber had been, reminding her that Ted had frequented some of the same locales. I told her about the publication of the Unabomber's manifesto, with its broad critique of technology. As I continued to outline the comparisons, she gazed at me with a strange look. Did she think I'd lost my mind? Was she horrified at the possibility that Ted might be a murderer? Or was she more horrified, perhaps, that I could think of my brother as a murderer?

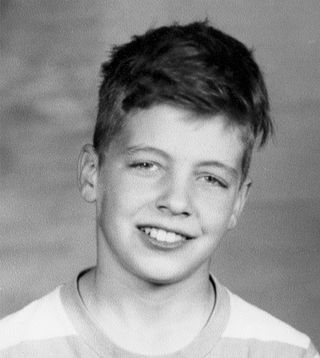

On the table next to Mom's chair was her favorite photograph of Teddy and me, a picture taken in our living room by a professional photographer when I was about three and Teddy about ten. Perched on my brother's shoulder was his pet parakeet. Teddy displayed much of the shyness but none of the rigidity evident in later photographs. Instead there was a softness, a vulnerability in his expression as he made himself a perch for the nervous little creature. My eyes glittered with pride, happy to be pictured with my big brother, pleased to be included at the center of attention.

By now I was crying, wiping away tears, and talking faster. I decided I'd better come clean: "Mom, I'm really concerned that Ted might be involved in these bombings. I'm really scared."

"Oh, don't tell anyone!" she blurted. It was the last thing I wanted to hear, but her reaction was understandable, even predictable, given a mother's instinct to protect her child. For years, she had been consumed with worry over her elder son's vulnerability. He was so different, so seemingly out of his element in a world of social conventions that most of us take for granted.

"Mom, I've already told someone," I said. "I've approached the FBI and shared my suspicions."

Life is full of tests, I suppose—tests big and small. Sometimes we see them coming, as Linda and I did, and sometimes they're sprung on us without warning, as happened to Mom that day.

After a stunned pause, she silently got up from her chair and came toward me. She was very small—under five feet—whereas I'm over six feet tall. She reached up, put her arms around my neck, and gently pulled me down to plant a kiss on my cheek.

"David, I can't imagine what you've been going through," she said. Then she told me the most comforting thing imaginable. "I know you love Ted. I know you wouldn't have done this unless you felt you had to."

With those words, I understood that I hadn't lost her love. I realized that the three of us—Mom, Linda, and I—would face this ordeal together.

A TENUOUS BRIDGE

When federal agents entered my brother's tiny cabin near Lincoln, Montana, on April 3, 1996, they discovered bomb-making parts and plans, a carbon copy of the Unabomber's manifesto, and—most chilling of all—another live bomb under his bed, wrapped and apparently ready to be mailed to someone. Feelings of resentment I'd developed toward Ted because of his hurtful treatment of our parents suddenly melted away. The way I was accustomed to thinking about him, my usual frame of reference, no longer worked. Now there was just emptiness and deep pity in my heart where my brother had been.

Two years later, Ted's trial ended with a plea bargain that spared his life while condemning him to life imprisonment without parole. The next day, Mom and I were ushered into a meeting room at the Federal Building in Sacramento. In the middle of the room were five upholstered chairs arranged in a circle. Sitting there was the widow of a man my brother had killed, her sister, and her late husband's sister.

The three women stood as we entered. Almost in unison, Mom and I said the only thing we could have under the circumstances: "We're sorry. We're so, so sorry."

However deeply we felt these words, they had a hollow, helpless ring. They were just words, unable to undo the harm that Ted had done.

The widow spoke first. "We may never meet again," she said. "We didn't want to miss this opportunity to speak with you and to tell you how deeply we appreciate what you did. Please convey our thanks to Linda as well. It must have been incredibly difficult to turn in a family member in a case like this. I can't imagine how painful it must have been."

The widow's expression of gratitude came so unexpectedly that it left me speechless. "We also want you to know that all we ever wanted was for the violence to stop," she continued. I believe this was her way of saying they hadn't wanted the death penalty for Ted. All five of us were crying. As survivors of tragedy, we had much in common.

But the mood changed dramatically when Mom started talking about Ted. He had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia by several forensic psychiatrists and psychologists who examined him after his arrest. Over the previous year, she had read and learned a great deal about the disease, and had come to understand that her son was one of the very small number of schizophrenics whose illness manifests in extreme paranoia and violence. Now, looking into the faces of three women whose lives had been utterly devastated by her son, she felt a deep need to help them see him not as a monster but as a very, very sick man. She needed them to appreciate that it was the illness—not Ted himself—that had done this terrible thing.

The widow stiffened. Instead of generating understanding, it was clear that Mom's words were producing pain. What the widow seemed to hear was someone making excuses for the man who had murdered her husband. "He knew what he was doing!" she said.

The room was frozen in silence. Five people had followed their best instincts to arrive at a place where reconciliation and some measure of healing had seemed possible. But now the aspiration and the journey appeared futile. There was no point in arguing about Ted's illness.

Across an immense gulf of pain and loss, we saw the faces of people on the other side, but it seemed there was no bridge that could carry us across—no way for Mom to completely understand what the widow was feeling, nor for the widow to completely understand what Mom was feeling. Each could empathize with the other to a degree, but not enough to overcome the distance. Meeting like this was a big mistake, I thought. If only there were some way to leave the room gracefully.

Mom looked at the floor, her small body hunched over. After a moment, she said: "I wish he had killed me instead of your husband."

The hardness in the widow's face slowly melted, replaced by concern. She eased herself down from her chair and knelt in front of Mom, looking up into her face. The widow's eyes were once again brimming with tears. She was a mother, too. On that level, she could relate. With quiet urgency, she said, "Mrs. Kaczynski, don't ever imagine that we blame you. It's not your fault. You don't deserve this burden."

Mom's early vision for her sons remains clear in my mind: It was that we would develop intelligence and compassion, and use our intelligence, guided by our compassion, to benefit humanity. This mission would allow us to live with integrity, providing us with the courage to make difficult choices. Mom pronounced the word "integrity" with reverence.

But the reality of life's journey, with its many obstacles and tests, is not so easy to formulate. In some ways Ted never stopped being his mother's son. Unfortunately, his capacity for empathy was eroded by his strong sense of personal injury and disappointment; his hope for the world was shattered by an apocalyptic vision. Beholding this threat through the distorting lens of his own illness, his sense of integrity became tragically twisted.

I will always love Ted, remembering with great fondness his many kindnesses to me when I was a small child. I mourn the loss of an older brother I once admired, his better self lost to the rages of a mental affliction that robbed him of his insight. Although I still love him, I despise what he did. Responsibility to me means taking responsibility for one's own suffering, finding in one's own pain the seeds of a wider compassion, not an excuse to inflict pain on others.

David Kaczynski is the author of Every Last Tie: The Story of the Unabomber and his Family, from which this article is adapted.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.