Fear

Do Emotions Feel the Same Across Different Cultures?

New research indicates that how we feel on the inside may be universal.

Posted January 15, 2020 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Evolutionary psychologist Paul Ekman—who achieved international recognition for his “atlas of emotions,” a compendium of more than 10,000 emotion-induced facial expressions—originally argued that there were six “universal” or “basic" emotions: joy, surprise, anger, sadness, fear, and disgust. Ekman used the term "basic emotions" to refer to these six because he had found that they were marked by unique facial expressions that can be found and recognized across almost all cultures.

In spite of this ubiquity of the basic emotions, a barrage of studies has shown that many other aspects of emotions (even the basic ones) vary across cultures. For example, different cultures have developed different ways of responding to traumatic loss. Culture shapes what types of loss are perceived as traumatic, how people interpret the concept of a traumatic loss, and how they react to it.

For example, in orthodox Islamic cultures, divorce is regarded as the “most despised of permissible acts by God” and is therefore often viewed as more traumatic than death. The display of grief exhibits even greater variation cross-culturally. Apart from cultural variation in funeral and burial rituals, whether grand emotional displays of one’s grief are encouraged or frowned upon is highly specific to a culture. In European Catholic and Protestant traditions, for example, it’s customary for people to grieve quietly and stoically, whereas African, Caribbean, and Islamic cultures encourage showing grief openly: for example, by crying loudly.

What triggers a given emotion also varies across cultures. Take disgust. In his classic book, The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin noted that what people find disgusting is substantially different in different cultures. Recalling an incident on his expedition to South America, Darwin observed:

In Tierra del Fuego, a native touched with his fingers some cold preserved meat which I was eating at our bivouac and plainly showed utter disgust at its softness; whilst I felt utter disgust at my food being touched by a naked savage, though his hands did not appear dirty.

More recently, psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett has argued that how the brain interprets certain physiological changes in the body varies not only across cultures and situations but also across individuals. Whether you interpret a particular bodily sensation as fear or thrill, for example, may depend on your personality, especially how excitement-seeking you are (a facet of extraversion).

Whether we are even able to experience a given emotion is also culture-dependent. Just as your great-great-great-grandmother wouldn’t be able to recognize a computational device left behind by a time traveler, such as a Macbook Pro, so you would not be able to experience jealousy if we humans weren’t in the habit of entering into relationships in which we feel entitled to other people’s love, time, and attention.

But according to a new study conducted by emotion researchers Sofia Volynets and colleagues, what emotions feel like does not seem to be subject to similar kinds of cultural influences. Rather, different emotions feel in much the same way when experienced by people across different cultures.

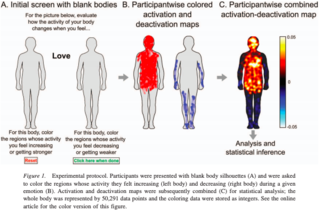

To determine whether emotions are felt differently across different cultures, the researchers asked a large group of participants from 105 countries to read an emotion word and then color in the areas on two body contours (Fig. 1A). The instructions asked them to base their coloring on how they feel when they experience the emotion in question, indicating increased activity on the left and decreased activity on the right (Fig 1B).

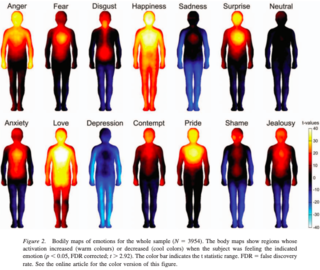

This question specifically asks about the participants’ memory of what an emotion feels like rather than what it actually feels like, but previous research has shown that this reporting technique is a good indicator of what an emotion actually feels like when experienced: 13 emotions, as well as a neutral or non-emotional state, were presented to the participants. Six of the emotions included were Ekman’s six basic emotions (anger, fear, disgust, happiness, sadness, and surprise), and seven were the nonbasic emotions: anxiety, love, depression, contempt, pride, shame, and jealousy.

After collecting the data, Volynets et al. combined the markings of activation and deactivation into a single map for each participant (Fig 1C). The team then selected 15 countries, which had at least 45 participants, in order to determine whether the bodily sensations associated with each emotion were similar across different cultures.

The data revealed that the 13 examined emotions plus the neutral state fell into distinctive clusters, or what one could call an emotion's “body signature,” with statistically significant agreement across the tested countries (Fig 2).

While cross-cultural variation in the feeling of the emotions was not statistically significant, the team did find a significant variation between Westerners and non-Westerners. Western participants reported greater activation in various body parts for fear, anxiety, disgust, happiness, love, pride, contempt, jealousy, anger, and while being neutral, whereas non-Westerners reported less deactivation for depression, sadness, and shame.

The body signatures for the 13 emotions were also found to vary with age and gender. The emotional intensity was negatively associated with age, indicating that younger people feel emotions more intensely than older people.

Compared to men, women reported feeling greater activation in their “gut” during anger, jealousy, anxiety, and shame, and in their throat and heart during anxiety, shame, fear, contempt, and sadness, but less activation in their legs when feeling surprised, depressed, and neutral. Men reported feeling greater activation in their genitals when experiencing love.

But the overlap of the body signature for the emotions was found to be greater than the differences due to culture, age, or gender. In other words, emotions are experienced in very similar ways across most cultures. So, what you feel when you experience, say, sadness is not all that different from what people in very different cultures across the globe feel when they experience the same emotion.

This may have implications for future research on cognitive empathy, or what is also known as "mind-reading." Mind-reading partially consists of determining what other people feel. So, these new findings might lend support to the suggestion that we can reliably use our imagination to figure out what other people feel like in different emotional states.

References

Barrett, L.F. (2006). “Solving the Emotion Paradox: Categorization and the Experience of Emotion,” Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (1): 20–46.

Barrett, L F (2017). How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. V. (1986). “A New Pan-Cultural Facial Expression of Emotion,” Motivation and Emotion 10: 159-168.