Philosophy

The Protective Power of Delusions

The case for purposeful as well as pathological delusions.

Posted June 27, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Delusions might play two valuable roles: to protect us from painful experiences or give us a way of understanding the world.

- Theorists have suspected for centuries that delusions have protective value.

- It may be unwise to invariably target the delusion as if it’s the disease itself.

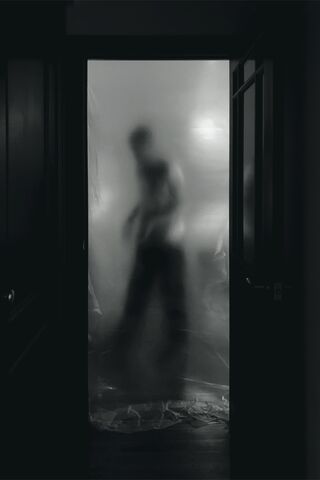

In the movie "A Beautiful Mind," a fictionalized John Nash decides to stop taking his antipsychotic medication. Within weeks, he begins to see coded messages everywhere. They alert him to a secret mission of global significance. When he finally encounters the imaginary Agent in Charge, Nash says, “I was so scared you weren’t real.”

With this line, the filmmakers hint that Nash’s delusions may have psychological benefits. They turn his boring academic existence into a breathtaking adventure. They give him a geopolitical mission of earth-shattering proportions.

Do delusions ever benefit those who suffer from them?

Consider what's known as Reverse Othello Syndrome. This is the delusional belief that one’s partner is sexually faithful, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Why would someone ever form this idea?

The discoverer of Reverse Othello thought he had the answer. He wrote that the delusion is “an active attempt… to confer meaning on otherwise catastrophic loss or emptiness.” The delusion might buffer our minds from an unbearable truth.

Philosopher Lisa Bortolotti calls such delusions “motivated delusions.” Along similar lines, psychologist Ryan McKay and philosopher Daniel Dennett describe the “shear pin” theory of delusion. Like a shear pin, a delusion might act as a little breakdown that stops a big breakdown from happening. Psychiatrist Rosa Ritunnano has also written on the purposeful character of some delusions.

Looking Back to History

Though the labels are new (“motivated delusions,” the “shear pin,” etc.), the idea isn’t. The German psychiatrist Johann Christian August Heinroth—the first person to use the word “Psychiatrie” in print—sketched this theory in his 1818 Textbook of Disturbances of Mental Life.

He describes how patients can enter a dream-like state in order to protect themselves from a traumatic experience:

"In a life which has been depraved by neglected education, circumstances, and guilts… a moment may come when the measure is full and runs over, and the imagination becomes strained to the limit in trying apparently to effect a full compensation and to transform the evil fate as though by the touch of a magic wand."

Heinroth saw profound implications for healing. If the delusions are playing a protective role, you don’t want to target them as if they’re the disease itself. By attacking the delusions, you might cause even more harm.

The pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, around the same time, wrote that delusions were nature’s way of protecting the mind from a reality too horrible to bear. Freud, an admirer of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, took it for granted that delusions protect us from otherwise devastating truths.

Making Sense of a Strange World

Delusions may have other benefits, in addition to protecting us from hard truths. They might help us make sense of hallucinations or other strange perceptual experiences. They can give us an anchor of meaning when our perceptual experiences start to change.

Consider Capgras Syndrome, the delusional belief that a person you love has been replaced by a perfect imposter. Some think Capgras happens when the parts of the brain that recognize faces, and those that stir our emotions, aren’t talking to each other.

To illustrate, suppose I see my wife, but the part of the brain that’s supposed to trigger a warm sense of familiarity isn’t responding. This would be a baffling experience. The person that I’ve known and loved for decades suddenly feels like a complete stranger.

In my perplexity, I race to come up with explanations: I know! She’s actually an impostor. Why is she doing this? Who is she working for? Suddenly everything makes sense. Now I can navigate this strange new world—and not get swept away in the psychological chaos.

Not everyone agrees that delusions are part of the mind’s evolved design. Philosopher Eugenia Lancellotta points out that even if some delusions, like Reverse Othello, are psychologically adaptive—they make us feel better—that doesn’t mean they’re biologically adaptive, meaning they help us survive better and have more children.

But I don’t think we can draw a sharp line between the psychological and biological benefits of delusions. As the field of cultural evolution has been telling us for some time, our beliefs and attitudes about the world can have direct consequences on our ability to survive on this planet.

For example, suppose a delusional belief, by protecting me from pain, also prevents me from ending my life. That’s both a psychological and a biological benefit—the kind of thing that evolution by natural selection takes note of.

So, are delusions good for you? Maybe the truth is somewhere in the middle. Perhaps there are different kinds of delusions, some purposeful and others pathological. Further research can help us decide. But the disease model shouldn’t be our default assumption.

For decades, the notion that madness must come from disease or dysfunction, a paradigm I’ve called “madness-as-dysfunction,” has had an iron grip on medical wisdom. I’ve described an alternative paradigm, which I call “madness-as-strategy,” which urges us to see purpose in mental illness, rather than pathology.

We shouldn’t demolish madness-as-dysfunction. Rather, we should learn how to adopt different perspectives on a complex reality. Being unable to step outside of old paradigms isn’t in the interest of science, and it’s not in the interest of people who seek professional help.