Identity

Why Other People Don't See Us the Same Way We Do

Identity, reputation, and their common mismatch.

Posted March 19, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- How we see our personality traits is our identity. How others see us is our reputation.

- Identity and reputation don't match nearly half of the time, so seeing each other differently is normal.

- Knowing this can help us understand why others' behaviour is often unpredictable and help us learn about ourselves.

What we think of ourselves, including our personality traits, is our identity. What others think of us makes us our reputation.

Reputations matter, and it also matters whether they match our identities. Although most want to be known as having desirable traits, we also wish to be seen accurately. For example, if people see our traits as we do, their behaviour towards us and our reactions are more predictable for everyone.

For instance, if you think you are a diligent person, but your partner does not, then his or her behaviour towards you may occasionally seem surprising. But if you mutually agree that you are not very diligent, then their same behaviour might not surprise you—even if it doesn't necessarily make you happy. Your reputation for low diligence matches your identity, so all makes sense.

Or, you may think that you don't have the personality traits expected from a leader, but your boss thinks differently and keeps assigning you leadership roles that stress you a great deal. But if your reputation did converge with how you see yourself, you may be assigned different roles, making your job less stressful.

Do people's reputations usually match their identities? Personality researchers have studied this for decades.

Self-Other Agreement on Personality Traits

For example, across hundreds of studies, thousands of people have completed personality tests about themselves and have someone else who knows them well also rate their traits. For each participant, this has given researchers two scores for each trait, one based on self-ratings and the other based on the other person's ratings.

How similar are the two kinds of trait scores, based on identity (self-ratings) and reputation (other-ratings), respectively?

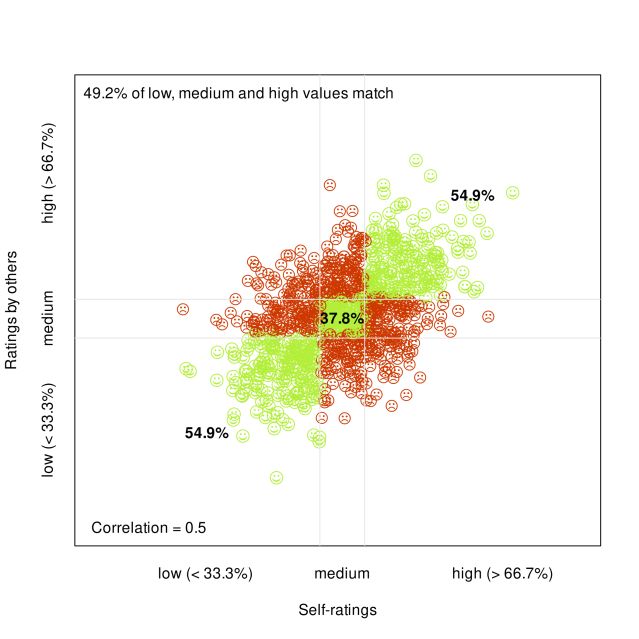

They are much more similar than one would expect by chance, but the agreement is very far from perfect. Specifically, trait scores based on self-ratings usually correlate with ratings by others at around 0.50. (Correlations can range from 0, showing no similarity between two variables, to 1, showing perfect overlap.)

Usually, partners agree on each other's traits slightly better than friends or relatives, although the difference is not large. Spending much of their time together helps people to learn some of each other's quirks that remain less known to others.

Also, the correlations tend to be slightly higher for traits that manifest in easily observable behaviours, such as extraversion and conscientiousness. For example, talkativeness is a facet of extraversion, and talking often is easy to see for both the talkers themselves and others. Or, orderliness is one conscientiousness facet, and its lack is easily visible to everyone.

So, How Well Does Your Friend or Partner Know You?

But let’s see what that 0.50 correlation between self- and other-rated trait scores actually means in real life.

Suppose 1,000 people complete a perfectly reliable extraversion scale about themselves and their partners. Upon completion, they are provided feedback on their scores, being in either the bottom, middle, or top third in extraversion. They get similar feedback about their partners. Next, their partners do the same and are similarly given two sets of feedback.

The question is: How often do people get similar feedback on their traits based on their own and their partner's ratings of these traits?

The chances of getting the same feedback are around 50-50. In other words, about half of people would find that their partners see their extraversion differently from how they see their own extraversion. For those scoring either in the bottom or top thirds, the probability of getting similar feedback from their partner is a little higher. But for those who see themselves in the middle third, their partners are more likely to think they are either low or high on extraversion.

Roughly the same applies to all Big Five traits.

Are Others Wrong About Our Traits?

So, our partners often see our traits differently than we do, and other people may agree with us on our traits even less often. But this does not necessarily mean that they are wrong about our traits.

In fact, it is often others who see us more accurately than we do see ourselves. For example, others' trait ratings are sometimes more accurate in predicting how well people perform at their jobs than people's own ratings. This means that others can pick up something about us that we cannot or are not willing to see. Other times, of course, we are the best judges of our personality.

This is why researchers sometimes recommend assessing personality with both self-ratings and others’ ratings and then combining them. The two types of information can make up for each other's flaws, and the truth is more likely to shine through in their combination.

We Have to Agree to Disagree

So, we cannot expect others to see us as we do. It is very common that others see us differently—for any given trait, it happens about half of the time.

On the one hand, this can cause unpredictability—it may be hard to understand why others behave towards us as they do. But when we see this happening, it may make sense to take notice and think about it. Others' perceptions of our traits are often just as accurate or even more accurate than our own, so we can learn from how others see us to better understand ourselves.

Facebook image: MilanMarkovic78/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Prostock-studio/Shutterstock