Child Development

Is Extreme Childhood Obesity 'Nutritional Neglect'?

How much are parents responsible for their children's excessive weight?

Posted September 14, 2016

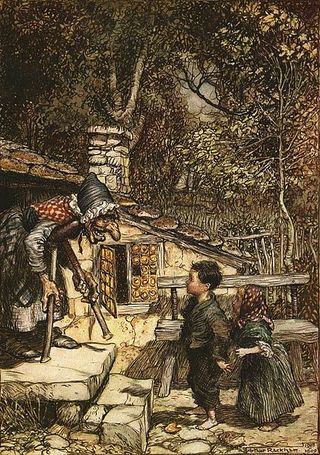

“…There was once more great dearth throughout the land.” So wrote the brothers Grimm in their classic tale Hansel and Gretel. We all know the story: A wretched stepmother “scolds and reproaches” a father until he relents and allows this woman to send his two young children deep into the forest. Wandering for days, with essentially nothing to eat, Hansel and Gretel discover a house made of sugar and cakes (and in some versions, gingerbread.) The house’s owner, though, is a wicked witch who initially feeds them “milk and pancakes, with sugar, apples, and nuts,” but alas, her goal is to fatten Hansel in order to cook him and eat him for her “feast day.” The story, with its ultimately happy ending, is beautifully depicted in the opera by 19th century composer Engelbert Humperdinck.

Aside from the obvious cannibalistic element in the story, we are confronted with a dreadful stepmother who is willing to starve and abandon children (child neglect) and a wicked witch who wants to fatten her child victims for own her ulterior motives (child abuse).

Is it child neglect or abuse to overfeed a child to the point where he or she becomes extremely obese? Some would think so. Former restaurant critic and now political columnist for The New York Times Frank Bruni, in his 2009 charming memoir Born Round, describes an experience his mother remembers when he was 18 months old: “My mother had cooked and served me one big burger, which would have been enough for most carnivores still in diapers.” Not only had toddler Frank wanted a second burger, but according to his mother, he started banging on his high chair tray for a third one. His mother was able to resist, despite a temper tantrum of “histrionic” proportions. Says Bruni, “A third burger isn’t good mothering. A third burger is child abuse.” (p. 10)

The topic of childhood obesity has become an impassioned one in recent years. Even the popular media outlets have entered the dialogue: Time featured an article “Should Parents of Obese Kids Lose Custody? (Faure, October 16, 2009) and Jon Stewart of The Daily Show, quipped, “If you are like me, every year we make a New Year’s Resolution to make our children lose weight." (January 3, 2011)

How do we define overweight and obesity in children and adolescents? There is some variation among researchers but most use the growth charts of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Since body mass index (BMI) is age- and sex-specific for this population, we don’t use the adult BMI table. Instead, overweight is defined as a BMI (i.e., weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) between the 85th and 95th percentile for children and adolescents of the same sex and age; similarly, obesity is defined as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile, and extreme obesity is defined as a BMI at or above the 120% percentile (Ogden et al, JAMA, 2016).

Given these norms, how prevalent is obesity in children and adolescents aged two to 19 years in the U.S? Ogden and her colleagues (2016) have been measuring over 40,700 children and adolescents since the late 1980s through the nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Their most recent data (years 2011-2014) found an obesity prevalence of 17% and extreme obesity of 5.8% among children and adolescents. Obesity rates, though, can differ significantly by ethnic and social class categories and even by state. For details, see the Ogden et al 2016 report or the CDC website.

Despite the fact that rates may be leveling off in some subgroups, there is no reason for complacency. In their editorial accompanying the Ogden et al report, Zylke and Bauchner (JAMA 2016), describe the situation as “neither good nor surprising.” These statistics are indeed alarming because obesity in childhood and adolescence is associated with increased medical morbidity, including abnormal glucose levels (and even overt type 2 diabetes), abnormal lipid levels, hypertension, sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, as well as psychological morbidity such as depression and stigmatization that often result from bullying. (Jones et al, Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 2014) Furthermore, we know that obese children tend to “track” into adulthood, with continuing potential for increased morbidity and early mortality.

While there are potentially damaging physical effects of childhood obesity, does the situation warrant some intervention by authorities? Murtagh and Ludwig (JAMA 2011) write that while “poor parenting is analogous to secondhand smoke in the home, there is a “well-established constitutional right of parents to raise their children as they choose.”

“The issue of governmental interference with parental rights for decision-making, such as the need to combat childhood obesity…has become a national debate that remains unresolved,” writes lawyer Denise Cohen (Cardozo Public Law, Policy, and Ethics Journal, 2012) Ms. Cohen maintains that though parents “have a unique role in reducing childhood obesity” they have not yet been “sufficiently engaged in this effort.” As a result, government may need to protect “the best interests of the child” by interfering with the private parental-child relationship. The situation is complex in that currently there are no federal or state laws that deal specifically with assessing and treating childhood obesity. Furthermore, many factors may contribute to the development of childhood obesity, including both genetic and environmental factors, and not all these factors are related to parental behaviors or “within parental control.” (Garrahan and Eichner, Yale Journal of Health Policy Law and Ethics, 2012) Yanovski et al (JAMA 2011) emphasize extreme childhood obesity is not de facto evidence of deficient or neglectful parenting and suggest that these children may be more likely to have “unrecognized single-gene defects” that may be contributing to their obesity. Harper (Pediatric Clinics of North America, 2014) highlights that obesity is rarely the result of only one factor but rather a combination of medical, genetic, and socioeconomic influences and requires “multidimensional assessment and management.”

Programs have addressed school physical fitness and school lunch, but these programs “fail to place any requirement on parents who are undoubtedly…the most influential people in their children’s lives.” (Cohen, 2012)

Parents can influence their children’s eating habits by their own food preferences and behavior (i.e. modeling) (Anzman et al, International Journal of Obesity, 2010) Further, parenting styles can have a significant impact on encouraging children to eat healthy foods: In their systematic review, Shloim et al (Frontiers in Psychology, 2015) found “indulgent and uninvolved parenting and feeding styles were associated with a higher child BMI; parents who were authoritative, i.e., “who combined expectations about adherence to a healthy diet and set limits on certain foods,”--parents who are responsive but not psychologically pressuring--(Sleddens et al, International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 2011), fostered healthier children and lower BMIs. Too much control and restriction, though, can backfire: authoritarian parents who pressure children to eat nutritious foods may promote overweight and even discourage healthy eating. (Scaglioni et al, British Journal of Nutrition, 2008) Likewise, Bergmeier et al (American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2015) found in their systematic review that children had a higher BMI when parents disparaged certain foods and made negative comments about them.

For a discussion of strategies to avoid (e.g. arguing with children; using food as a reward in an if-then scenario; forcing children to eat; cooking meals exclusively for children; and eating separately from children), see Russell et al, Appetite (2015) and Gibson et al, Obesity Reviews (2012.) Berge et al (JAMA Pediatrics, 2013) found that disordered eating was more likely to result when parents emphasized weight rather than healthy eating. Interestingly, Wolfson et al (The Millbank Quarterly, 2015) found that both men and women did attribute blame and responsibility to parents for childhood obesity though they also felt there should be “broader policy action” such as school-based programs.

Cohen reviewed legal cases in which the specific rights of parents have been addressed; these fall under the liberty and privacy aspects of the Fourteenth Amendment. She notes that courts “have generally accorded great deference” to parents. This right to privacy can be challenged, though, when there is concern that a child has been neglected or abused, and definitions vary by state but fall “within the range provided by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA)” of 1974. There is a long history of children being removed when they have been severely malnourished; more recently some extremely obese children have been removed from the home for neglect when “childhood obesity becomes life threatening” and there is a “compelling interest in preventing harm.” (Cohen, 2012) Further, many parents of obese children are obese themselves and “treating the obese child of an obese parent as neglected has the effect of criminalizing obesity among parents.” (Cohen, 2012) In a large study, Trier et al (PLOS One, 2016) found that the prevalence of obesity or overweight among the parents of children and adolescents presenting to a childhood treatment program can be as high as 80%.

Lawyers Garrahan and Eichner (2012) focus on the “increasing need” for state courts to intervene in cases of childhood obesity when parents “negligently fail to address the medical needs of their morbidly obese children.” Jones et al (Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 2014) note that a state can order removal from a home but must “prove imminent danger to the physical health or safety of a child, determine whether it is contrary to the welfare of the child to remain at home and make reasonable efforts to prevent the removal.” Only recently has overfeeding been seen as being as “harmful as underfeeding.” They further note that based on recent court cases, “…the designation of childhood obesity as a form of child abuse or neglect is quickly becoming a legal reality in the U.S.” In other words, “morbid obesity is essentially nutritional neglect.” Getting child protective services involved early on should not be seen as punitive but rather about educating and helping a family. Cohen (2012) makes the point, though, that it is not always clear that removing a child to a foster home is necessarily a better option. Siegel and Inge (JAMA, 2011) found there are actually few data that support using foster care for obese children, and note that foster care may even be an “obesogenic environment” itself.

The obesogenic environment, though, is potentially everywhere. For example, should local governments be able to prohibit restaurants from providing free toys with children’s meals that do not meet established nutritional guidelines? When San Francisco and Santa Clara County passed their Healthy Food Ordinance in 2010, they were accused of fostering a paternalistic “nanny state,” (with concerns of a “paternalistic slippery slope”) not unlike the response to former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s proposal to limit the size of sodas. (Etow, American University Law Review, 2012) (For more on the NYC soda-size ban, see my previous blog.) The Healthy Food Ordinance even garnered the attention of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (January 3, 2011): correspondent Aasif Mandvi recommended that a “Crappy Meal” be equipped with the Periodic Table of Elements, CPR instructions, and an action figure of the then Head of Health and Human Services.

Bottom line: Clinicians should be “mindful” of the potential role of abuse or neglect in contributing to childhood obesity (Viner et al, British Medical Journal, 2010), but just because a child fails to lose weight alone does not constitute potential negligence or abuse. After all, weight management programs for childhood obesity do not necessarily lead to weight loss. On the other hand, there are red flags when parents fail to keep appointments, refuse to work with professionals, or actively sabotage weight management treatment plans. Further, it is essential for there to be a full multi-disciplinary evaluation, encompassing all aspects of a child’s medical, physical, and emotional environment.

For an excellent book on children and eating, see also Bee Wilson's First Bite: How We Learn to Eat (2015).