Trauma

How Trauma, Nutrition, and Mental Health Fit Together

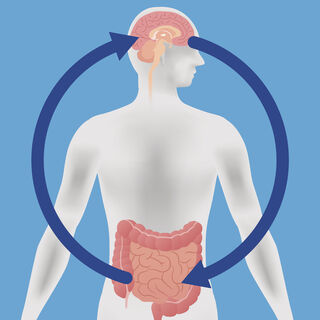

Trauma-informed nutrition leans on the gut-brain axis for help with healing.

Posted November 23, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- The gut-brain axis is a complex bidirectional communication system that affects both gastrointestinal and brain function.

- A history of historical, systemic, and individual trauma can significantly impact health markers, eating habits, the gut biome, and the brain.

- Studies of mental health and nutrition suggest promising new strategies that can help with trauma, depression, IBS, and eating disorders.

This post was written by Gia Marson, Ed.D.

Trauma’s impact on the body, mind, and spirit is well established, but the connection between trauma, nutrition, and mental health has only recently started to be explored. The brain and gut share a strong connection thanks to the brain-gut axis, meaning that a disruption at either end can impact the other. Importantly, though, it also means that nutrition may be a powerful tool in mental health treatment.

“Trauma and adversity of any kind can disrupt biology and exacerbate an unhealthy relationship with food, leading to poor nutritional health.… Trauma-informed nutrition acknowledges the role adversity plays in a person’s life, recognizes symptoms of trauma, and promotes resilience... characterized by an understanding that unhealthy dietary habits, chronic disease, and poor health outcomes may be a result of adverse experiences and not individual choices, and therefore aims to avoid shaming, stigma, and blame.” —California Department of Public Health

The gut-brain axis

The communication network between the gut and brain is known as the gut-brain axis or the enteric nervous system. Neurons are found in both the brain and gut, and research tells us that there is a bidirectional connection between the two organs through the nervous system. This complex communication system is likely to affect not only gastrointestinal function but also higher cognitive functions like intuition and motivation.

Neurotransmitters also feature in the gut-brain axis, so feelings of happiness or anxiety could be triggered through the gut. This type of connection is already well known through common embodied experiences like nervous “butterflies” in your stomach or feeling nauseated during times of stress.

The connection between trauma and eating disorders

Research tells us that the impact of trauma on healthy eating habits may, in some cases, lead to the development of eating disorders. People who experience traumatic or adverse life experiences, for example, are at higher risk for binge eating disorder.

Because intestinal microbiota has a crucial role when it comes to the immune system, metabolic functioning, and weight regulation, the gut-brain axis may be useful as a tool in treating eating disorders. Not only is nutritional support imperative for refeeding those with anorexia nervosa and for creating structured eating for those with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, gut-brain modulators (such as probiotics) have shown potential as added interventions.

When the gut-brain axis goes wrong

When it comes to our basic need for nourishment, trauma can interfere with healthy eating. Traumatic experiences can have impacts on food-related experiences and behaviors including:

- Eating without routine.

- Stocking up on food.

- Losing control with food.

- Restricting or controlling food.

- Consuming high-fat, sugar, and/or salt diets.

- Body shaming experiences.

- Relying on easy-to-access foods.

- Experiencing food scarcity.

- Basing decisions about food on short-term needs.

- Feeling shame utilizing food assistance.

- Difficulty planning and budgeting for food.

While the gut-brain connection means that proper nutrition may result in substantial improvements to mental as well as physical health, disturbances to either side of the axis may contribute to problems. For example, it can also lead to eating disorders and anxiety: Both produce physiological imbalances that alter the amount and composition of gut microbiota.

Another way that we see this disturbance is in the high correlation between anxiety and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). In some studies, participants with anxiety showed lower microbial richness. More than 50 percent of IBS patients have comorbid depression or anxiety, and it is thought that disturbances to microbiota like those seen in IBS patients may be contributing to these symptoms.

Improving IBS could, therefore, result in improved mental health. But interestingly, prescribing patients antidepressants may also help reduce some of the symptoms of IBS. A study of adolescents with newly diagnosed IBS found that the antidepressant amitriptyline significantly reduced symptoms and increased overall quality of life.

The healing power of food

“Let food be thy medicine, thy medicine shall be thy food.” —Hippocrates

Food isn’t just good for nourishment; it turns out that it can also help the body and the mind heal after trauma. Trauma-informed nutrition is an emerging area of psychology and medicine. By drawing on what we know about the impact that the gut biome can have on the brain, it may be possible to use nutrition as part of the therapy for the treatment of trauma, trauma-related illnesses, and depression.

The SMILES trial, conducted in 2017, investigated the impact of a dietary intervention on depression. Over 12 weeks, participants in the single-blind randomized controlled trial received either nutritional support or social support. Participants who received nutritional support experienced significantly greater improvements to their depression symptoms than participants who received only social support. Thus, nutrition-informed treatment may be an accessible way to help individuals with depression.

The HELFIMED study also found that diet can improve mental health. Participants who received a Mediterranean-style diet combined with supplementary fish oil experienced significant improvements in depression symptoms and overall mental health.

“...neural reward thresholds can be changed in favour of preferring healthy over unhealthy food. A Mediterranean diet not only has demonstrated health benefits but is also a highly palatable diet and thus more likely to become a sustainable part of a healthy lifestyle.” —Natalie Parletta, et al.

Improve your brain-gut axis

Here are some ways to support whole-body health, starting with the brain-gut connection:

- Acknowledge that historical, systemic, and individual trauma may negatively impact physical health, mental health, and eating habits.

- Focus on holistic well-being rather than weight or BMI.

- Embrace new research that suggests that the gut-brain axis is bidirectional: Nutrition interventions may support recovery from mental health conditions and psychological interventions may help reduce symptoms in gastrointestinal and other health conditions.

- Reduce shame, stigma, and blame around the impact of trauma on health, eating, and weight.

- Accept that some nutrition practices may be triggering after adverse childhood experiences and/or traumatic experiences in adulthood.

- Practice cultural humility when it comes promoting resilience.

- Address conscious and subconscious bias about eating, health, and mental health difficulties.

References

Navarro-Tapia, E., Almeida-Toledano, L., Sebastiani, G., Serra-Delgado, M., García-Algar, Ó., & Andreu-Fernández, V. (2021). Effects of Microbiota Imbalance in Anxiety and Eating Disorders: Probiotics as Novel Therapeutic Approaches. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(5), 2351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052351

Achamrah, N., Dechelotte, P., & Coeffier, M. (2019). New therapeutic approaches to target gut-brain axis dysfunction during anorexia nervosa. Clinical Nutrition Experimental, 28, 33-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yclnex.2019.01.006

Bahar, R. J., Collins, B. S., Steinmetz, B., & Ament, M. E. (2008). Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics, 152(5), 685–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.10.012

California Department of Public Health | California Department of Social Services Essentials for Childhood Initiative. (2020). Trauma-informed nutrition: Recognizing the relationship between adversity, chronic disease, and nutritional health.

Jacka, F. N., O'Neil, A., Opie, R., Itsiopoulos, C., Cotton, S., Mohebbi, M., Castle, D., Dash, S., Mihalopoulos, C., Chatterton, M. L., Brazionis, L., Dean, O. M., Hodge, A. M., & Berk, M. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the 'SMILES' trial). BMC Medicine, 15(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

Kim, Y. K., & Shin, C. (2018). The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Novel Treatments. Current Neuropharmacology, 16(5), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666170915141036

Mayer E. A. (2011). Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(8), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3071

Palmisano, G. L., Innamorati, M., & Vanderlinden, J. (2016). Life adverse experiences in relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.018

Parletta, N., Zarnowiecki, D., Cho, J., Wilson, A., Bogomolova, S., Villani, A., Itsiopoulos, C., Niyonsenga, T., Blunden, S., Meyer, B., Segal, L., Baune, B. T., & O'Dea, K. (2019). A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutritional Neuroscience, 22(7), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320