Stress

Cortisol Sensor Uses Sweat to Monitor a Biomarker of Burnout

Monitoring cortisol levels in human sweat is a new way to track chronic stress.

Posted February 7, 2021

Many moons ago, on a scorching hot summer day, I was working out in Central Park alongside lots of other sweaty New Yorkers when the words "sweat and the biology of bliss" popped into my head; despite being covered in sweat, the joggers and bikers doing cardio on this sunny day seemed happy. These six words became the subtitle for The Athlete's Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss.

In my mind's eye, the imagery of this phrase conveys that even though exercise-induced neurochemicals (e.g., endorphins, endocannabinoids) associated with "runner's high" are hidden from view, these feel-good molecules are represented externally in the beads of perspiration that form on someone's skin during a vigorous workout. "All I picture now when I see people sweat is the joie de vivre radiating from them in the form of neurochemicals pumping inside their brains symbolized by sweat streaming from their skin," is how I summed it up in my first book.

Of course, the exercise-induced sweat we experience during an exuberant workout is different than the kind of sweat advertisers are referring to with taglines like, "Never let them see you sweat."

This antiperspirant ad slogan refers to the type of sweat people experience when they're nervous and stressed out. In addition to any preconceived notions people might have about "stressed-out sweat" versus "work-out sweat," evidence-based research suggests these different types of sweat contain specific biomarkers (in minuscule quantities) that can be used to assess someone's psychophysiological state as he or she is perspiring.

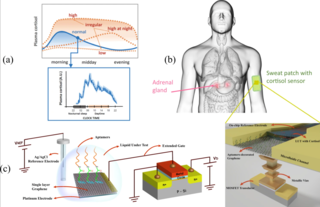

Interestingly, new research shows that stress-induced sweat contains measurable amounts of cortisol, which can now be monitored with a wearable skin patch called an EG-FET (extended gate-field effect transistor). This state-of-the-art "smart patch" has a miniaturized sensor that measures cortisol concentrations in human sweat throughout the day and can detect signs of burnout via this biomarker. This wearable sweat patch with a cortisol sensor is still in its developmental phase and is not yet available for purchase or clinical use.

The EG-FET was recently developed by a team of Swiss engineers at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne's Nanoelectronic Devices Laboratory (Nanolab) in conjunction with Xsensio, who are known for their trademarked "lab-on-skin technology." A scientific paper (Sheibani et al., 2021) announcing this invention, "EG-FET for Sensing Cortisol Stress Hormone," was published on Jan. 19 in the open-access journal Communications Materials.

"The [EG-EFT] device shows promising experimental features for real-time monitoring of the circadian rhythm of cortisol in human sweat," the authors write in their paper's introduction. "[This] device can be placed directly on a patient's skin and can continually measure the concentration of cortisol, the main stress biomarker, in the patient's sweat."

A Dual-Edged Sword: Cortisol Helps in Times of Short-Term Eustress, but Harms During Periods of Long-Term Distress

Cortisol is referred to colloquially as the "fight-or-flight" stress hormone; this glucocorticoid is produced by the adrenal glands and released in response to both eustress ("healthy" stress) and potentially harmful distress.

"When we're in a stressful situation, whether life-threatening or mundane, cortisol is the hormone that takes over. It instructs our bodies to direct the required energy to our brain, muscles, and heart," the authors explain in a news release. "Cortisol can be secreted on impulse—you feel fine and suddenly something happens that puts you under stress, and your body starts producing more of the hormone," senior author Adrian Ionescu, director of EPFL's Nanolab, added.

Through the lens of challenge/threat appraisals, eustress tends to involve challenging (but doable) obstacles that can be nerve-wracking but don't trigger crippling anxiety or chronic worry. For example, training hard for your first marathon and then waking up on race day with butterflies in your stomach while getting psyched up to seize the day is an example of short-term eustress.

Any time you need a quick hit of oomph to get-up-and-go, cortisol is your ally. Cortisol can provide a psychophysiological boost that facilitates staying motivated and focused during eustress-inducing challenges. That said, persistently high levels of cortisol caused by chronic distress are toxic. (See Cortisol: Why the 'Stress Hormone' Is Public Enemy No. 1.)

In healthy individuals who aren't perpetually stressed-out or experiencing burnout, cortisol levels tend to rise and fall in tandem with daily, 24-hour circadian rhythms. Ideally, cortisol concentrations aren't consistently high or low but rather ebb and flow in ways that appear to be influenced by circadian cycles and the rising/setting of the sun. For example, in healthy adults, cortisol levels typically peak between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. as the sun is rising in the morning hours and hit their lowest concentration levels around midnight. (Chan & Debono, 2010)

That said, because cortisol release is modulated by the HPA axis, extended periods of unhealthy distress can disrupt the natural ebb and flow of circadian-mediated cortisol levels. "Although the short-term activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is adaptive and necessary for everyday life, both high and low levels of cortisol, as well as disrupted circadian rhythms, are implicated in physical and psychological disorders," Sheibani et al. explain.

"[In] people who suffer from stress-related diseases, this circadian rhythm is completely thrown off," Ionescu notes. "And if the body makes too much or not enough cortisol, that can seriously damage an individual's health, potentially leading to obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, or burnout."

According to the researchers, the EG-FET device is the first wearable sensor that can monitor cortisol levels throughout the circadian cycle. "That's the key advantage and innovative feature of our device. Because it can be worn, scientists can collect quantitative, objective data on certain stress-related diseases," Ionescu concludes. "And they can do so in a non-invasive, precise and instantaneous manner over the full range of cortisol concentrations in human sweat."

Fig. 1 image by Sheibani et al., 2021/Communications Materials (open access) Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Shokoofeh Sheibani, Luca Capua, Sadegh Kamaei, Sayedeh Shirin Afyouni Akbari, Junrui Zhang, Hoel Guerin, Adrian M. Ionescu. "Extended Gate Field-Effect-Transistor for Densing Cortisol Stress Hormone." Communications Materials (First published: January 19, 2021) DOI: 10.1038/s43246-020-00114-x