Relationships

The Dark Side of Mythic Quests and the Spirit of Adventure

A quest for the holy grail through otherworldly peak experiences can be fatal.

Posted September 12, 2015

I almost killed myself in a mythic quest for a Guinness World Record. For me, ultra-endurance sports was always about the spirit of adventure and was akin to climbing Mt. Everest. I wanted to run, bike, and swim as far—and as fast—as humanly possible in the most extreme conditions. The ecstasy and glory that I experienced in my pursuits of the 'holy grail' through athletics was like a drug ... it took me very high, but also had the potential to become a form of self-sabotage.

The human experience of pursuing otherworldly peak experience can be glorious and life-affirming, but it can also lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or mortality. The quest for otherworldly peak experiences can be fatal. Sometimes, the hero never returns home with the magic elixir or wisdom gained from his or her odyssey—as is the case in the upcoming film Everest.

Watching the Everest trailer reminded me of the dark, and potentially deadly aspects of mythic quests and the spirit of adventure. “Summit Fever” can drive mountain climbers to choose reaching the top of a mountain over returning home. I can identify with this mindset as an extreme athlete with a spirit of adventure.

The Power of Myth: "May the Force Be With You"

Any "Hero's Journey" or quest for the holy grail has a dark side, a lighter side, and is riddled with paradoxes. The archetypes, metaphors, and characters in all the Star Wars movies illuminate the timeless nature of myths that span all cultures and generations.

Joseph Campbell’s 1988 PBS documentary The Power of Myth with Bill Moyers was filmed at Luke Skywalker ranch. Star Wars embodies many of the classic archetypes of myths that have been a part of the global human experience since the beginning of time. When I was 11-years-old in 1977, I went to see Star Wars about 17 times and the archetypes got deep into my subconscious, although I didn’t really understand them at the time.

Luckily, as an extreme athlete, I had learned from The Power of Myth that completing the hero’s journey isn’t just about finding the holy grail or achieving a peak experience—the hero must return home to your loved one's, family, and local community alive. A true hero who goes on a self-imposed mythic quest must also assimilate back into common daily life while staying tethered to the “otherworldly” wisdom he or she has gained from their personal odyssey without needing to go back into the belly of the beast. One must live to tell the story.

So many of my athletic peers found it impossible to unplug from their Spirit of Adventure, which had become a part of their identity as ultra-endurance athletes. They couldn't stop pursuing the holy grail through extreme sports. I knew in my case that the Norwegian Viking genes and memes that were a part of my DNA, and drove me to push the envelope to the outer reaches of human possibility through mythic quests, would lead to a form of suicide.

Rites of Passage and Peak Experiences: Leaving the Mundane World

As a young adult, The Power of Myth allowed me to realize in the most beautiful way that I was both extraordinarily unique but nothing special. My personal life experience and rites of passage were nothing new. The archetypes, trials, and tribulations that I would face as the protagonist in my own life had all been played out before in an archetypal way. Understanding universal archetypes, myths and their various outcomes was like a crystal ball that allowed me to foresee the consequences of the decisions I made and the people I befriended.

I almost self-destructed as a gay teenager stuck in a stodgy boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut. I had a dean who got his kicks from bullying and forever pointing out that I was an unathletic sissy. At the time, my Kamikaze friends and I would drink liters of vodka every week and take recreational drugs excessively. I was trying to escape by becoming ‘comfortably numb.’

Interestingly, the first time I tried psilocybin it cleared my windows of perception in a way that William Blake described. It made me realize the interconnectedness of everything and that I could tap into the energy of the universe in a way that was frictionless. This experience would later inspire my quest for a state of superfluidity as an athlete when I stopped taking drugs and drinking as a teenager. Running was a way for me to pierce through to another plane of consciousness where I could have otherworldly peak experiences.

Coming Out During a Pandemic Inside the Belly of The Beast

After graduating from Hampshire College in 1988, I moved into a studio apartment on Gansevoort St. in the Meat Packing district. My rent was $325 a month. In many ways the zip code 10014—which is a very swanky neighborhood today—was very gritty, and ground zero for HIV/AIDS as I was coming of age. Early in the 80s I had been sexually promiscuous but now my friends were dying all around me from AIDS. I sublimated my libido and poured all of my energy into running.

By 1989, the AIDS epidemic was wiping out thousands of my Manhattan comrades. I lived in the West Village at the time, just a block away from the community center and St. Vincent's hospital and worked as a waiter at Benny’s Burritos on Greenwich Avenue to pay the bills. My father hated that I was waiting tables for a living and was perpetually trying to bribe me to stop being a waiter. The fact that I was a server in a restaurant embarrassed him in a way that really irritated me.

My father lived on the polar opposite side of Manhattan, on East End Avenue, and we were estranged. But in 1990, my dad twisted my arm into taking a job on Madison Avenue in advertising that he’d arranged and he was going to buy me some new suits.

I showed up at Saks Fifth Avenue in my ACT UP uniform: Doc Marten combat boots, aviator sunglasses, cut off Levi's and an ACT UP T-shirt with a red handprint dripping ink on the front. On the back it said, “THE GOVERNMENT HAS BLOOD ON ITS HANDS.” The ultimate showdown with my father happened in the suit department at Saks. We didn’t speak for almost ten years after this event and I refused to take a dime from him.

Having autonomy from my father was healthy. I learned to be completely self-reliant financially and it fortified my determination to be a maverick and trailblazer in non-conventional ways. My father was always a radical thinker and politically progressive, but in the 1980s the whole "gay thing" still freaked him out. I was also very anti-establishment and he was a member of the NYC old boys' network who played squash together and ate lunch at places like 21 Club.

My father and I had reconciled—and we had achieved atonement—when he died unexpectedly in 2007. My dad died in a La-Z-Boy surrounded by dozens of copies of my book and a picture of my daughter in a frame in front of him. Knowing this brings me tremendous peace, as I still strive to make him proud.

Going on epic odysseys as an athlete was a way for me to cope with the genocide that I lived through in the West Village, at a formative stage of growing into my manhood. I also didn’t have any mentors—most of my gay elders, my potential Jedi Masters per say, were very sick and dying, too. I've never felt so alone. If it wasn't for ACT UP I would have completely evaporated.

Young adults need to form intimate, loving relationships with other people. Success leads to strong relationships, while failure results in loneliness and isolation. I never experienced intimate sexual relationships due to a fear of AIDS, I am damaged goods. Yes, I survived the plague but my oxytocin receptors are all messed up. The scaffolding was never laid down and atrophied due to a fear of dying if I shared intimacy with a romantic partner.

If there was a confluence of forces that drove me to seek mythic quests in my early 20s it was threefold. The first reason was that I had completely sublimated my libido because I equated sex with death—celibacy was my only choice. Instead of forming intimate relationships, I would go to this mysterious place when I ran. I'd go through some type of pinhole in which I felt that I connected with the ‘other’ in an ecstatic, orgasmic kind of way.

This feeling of zero friction and viscosity reminded me of the oneness—or superfluidity as I call it now—I had felt on psilocybin. Now that I was 100% drug free, I wanted to experience this organically and running took me there.

The last catalyst was that I began psychoanalysis at the White Institute, on the Upper West Side, in 1989. The sickness and death that surrounded me were taking a toll on my psyche. By the early 90s I had grown frustrated with my analyst for not giving me any direct feedback or answers to help me with my dilemma. I decided to make myself the protagonist in my own life story.

The archetypal stages of the hero’s journey became an easy template that I could plug myself into. I romanticized the whole thing. Athletics took me away from the hopelessness and fear of witnessing loved ones losing their life force due to complications from AIDS.

Writing about it now still makes me well up with tears. It was such a traumatic experience that no rites of passage had prepared me for. Anyone who could have been a mentor was focused on the gay men's health crisis or sick. The late 80s and the Reagan Era were a very lonely and isolating time. Homophobia ran rampant. I’ll always be grateful to Madonna and ACT UP for having the balls to make the AIDS epidemic a public issue, at a time when it was very unpopular. If you'd like to watch a Vimeo video of me describing this era click here.

Love What You Do, Pour Your Heart Into It, and You Will Be Rewarded

Bringing ultra-endurance racing and the odyssey of mythic quests home, to the East Village, and Kiehl’s Since 1851, who has been my employer and title sponsor since the early 1990s, was the perfect end to my athletic career.

I had started working at the Kiehl’s flagship store, at 13th and 3rd Avenue, because Jami Morse and Klaus von Heidegger loved my chutzpah and the spirit of adventure I had as an athlete. Kiehl’s put their trademarked Harley-Davidson inspired wings on my back and sent me off to push the envelope and pour my heart into Ironman triathlons and other ultra distance races around the world.

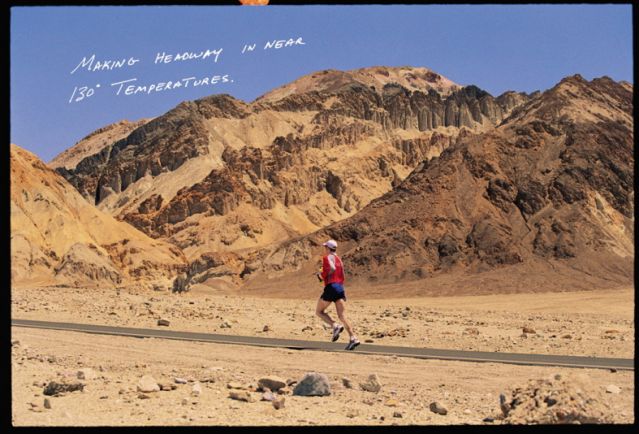

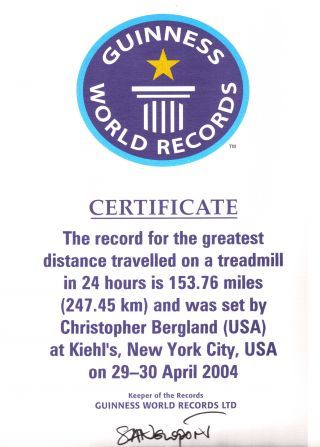

Some of my adventures included running 135 miles through Death Valley in July, in temperatures that reach 130° F, and winning the Triple Ironman, three years in a row. As I approached 40 years of age, I knew that I was getting a little long in the tooth and would be over the hill soon. I felt like an aging race horse that would soon be put out to pasture. I really wanted a Guinness World Record for posterity and something that would outlast me.

I decided to bring the epic odyssey of ultra racing home to the East Village. Dean Karnazes and I agreed that we would dual it out side-by-side on treadmills in the window of the Kiehl's flagship store to see who could run farther in 24 hours. At this point, my "summit fever" put my life at risk. I would do anything to be the last man standing.

We were also raising money for YouthAIDS and had a third treadmill set up next to us for random runners to experience first-hand what Dean and I were going through by running for a couple hours, without having to stick it out for the entire 24. For me, as a native New Yorker, the “Treadathalon” brought together my spirit of adventure with my post 9/11 and AIDS crisis mantra, "I'm alive, dammit!" My determination to live fully and completely was fueled primarily by those who had died and no longer had the opportunity to seize the day.

That said, the event literally almost killed me and was a wake up call to the dark side of mythic quests and my neverending pursuit of the holy grail. After running 153.76 miles I found myself in the ICU for the next three days. On page 39 I write:

From about 7AM, twenty-three hours into the run, till the end, I don’t really remember anything, but I ran another hour at seven miles per hour and I had no idea where I was, what direction I was facing, what time of day it was, or who I was. My ego was gone. I was blacked out, but I was running. That is what amazes me. I was able to keep running from so many years of conditioning laid down in the Purkinje cells of my cerebellum. The innate collective unconscious memory of running stored in my cerebellum for millions of years allowed me to run without a fully functioning cerebrum. I put one foot in front of the other in a purely instinctive way.

It was surreal to watch myself on the NY-1 news loop on the TV in the ICU later that morning, witnessing something I had no recollection of. I was catheterized and on the verge of kidney failure with CPK levels of 176,700 international units per liter (normal is 24 to 195 IU/L). CPK is a byproduct of muscle breakdown and is a gloppy and viscous fluid that blocks the filtering screen of the kidneys. My CK-MB, an enzyme that measures heart muscle breakdown with a normal range of 0 to 34.4 ng/ml was at 770 nanograms per milliliter.

The saddest lesson I learned from the post-treadathalon blood work was that, in an attempt to squeeze every ounce of passion from my body, my heart had begun to eat itself. That sucked. My own desire to suck the marrow out of life would eventually cause me to self-destruct. I made a vow in the ICU that I would never push my body to the limit again.

The treadathalon was the last time I will ever take my body to the point of obliteration. I proved once and for all that I had enough mental toughness to kill myself. I had pushed the quest for adventure to a point of self-destruction.

Myths served as a road map for me in a way that made it easier to navigate the potential pitfalls and booby traps of my aching desire to leave the mundane workaday world and have otherworldly peak experiencing. Letting go of mythic quests that took me to exotic locations and living a more sedentary and cerebral life in the quest for new ideas is how I've chosen to channel my spirit of adventure in older age.

Generativity vs. Stagnation

Based on my rudimentary understanding of mythology and psychology, I knew that in Middle Adulthood (40 to 65 years) I would face the basic conflict of generativity vs. stagnation. I would have to reinvent myself for the next phase of life based on Erik Erikson's stages of psychosocial behavior and the archetypes held in mythology. The term "generativity" was coined by the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson in 1950 and denotes "a concern for establishing and guiding the next generation."

At age 41, I became a parent and published my first book The Athlete’s Way (St. Martin’s Press). Instead of pouring myself into ethereal athletic feats, I decided to dedicate my time and energy to creating and nurturing earthly things that will outlast me. Again, just like the mountain climbers who never return from Everest, I didn’t want my hero’s journey to end tragically in pursuit of otherworldly peak experiences.

When my father died, I picked up the torch and dedicated myself to the quest to prove his neuroscientific hypotheses. It’s endlessly rewarding and exciting to wake up every morning looking for new clues. And to be on the edge of a new frontier of understanding the structure and function of the human brain. I feel lucky to be able to do this from my laptop, no longer slaying dragons and facing tempests. My body couldn’t take it. I’d be dead if I tried to find peak experiences the same way that I did in my 20s and 30s.

There is one important caveat. I still crave the moments of superfluidity and the ecstasy that I experienced through the adventures I had as an ultraendurance athlete. Although it’s been a decade since I retired, I’m still trying to be a “Master of Both Worlds.” I feel malcontent sometimes. My moments of awe and a sense of wonder are much more fleeting than they used to be, but I'm learning to embrace serenity.

Yes, I derive pleasure from the simple joys of life but it doesn’t give me the adrenaline rush of adventure. In a simplified neurobiological way, I realize that the adrenaline, endorphins, and endocannabinoids that fueled me as an athlete have diminished. Oxytocin, human bonding, and connecting with my daughter are the prime driving forces in my life today.

Conclusion: There’s No Place Like Home

Interestingly, when you look at the Wizard of Oz through the lens of the hero’s journey you realize that Dorothy went through all the classic stages of the monomyth and returned to Kansas with a new appreciation and contentment for her simple life. Embracing the simple life and having commonplace peak experiences is still a work in progress for me.

Brené Brown hits on something really important when she talks about vulnerability and living wholeheartedly. And that ultimately, all we really want and need is to feel worthy of love and belonging. Everyone wants to feel safe, grounded, and part of a community. We also have a need and desire to step out of our comfort zones and optimize our full human potential by nurturing a spirit of adventure and going on mythic quests that fit our personality.

The most important part of the hero’s journey isn’t standing on the top of a mountain and saying “I did it” and then self-destructing... the end of the journey has to be about generativity and finding ways to use your age and wisdom to make the world a better place. If you never make it home after finding the holy grail, the dark side wins.

© 2015 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete's Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.