Conformity

We Are Wired for Moral Cowardice

Why it's so hard to oppose the crowd.

Posted July 27, 2020 Reviewed by Devon Frye

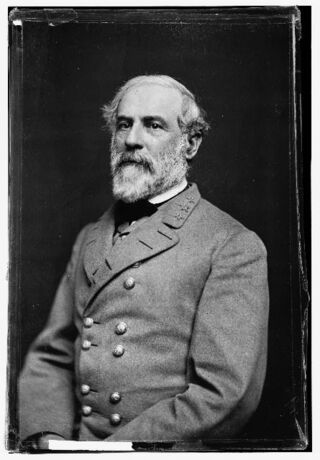

With reassessments of historical figures occurring regularly nowadays, it’s only right that a 1928 essay by W. E. B. Du Bois, skillfully dissecting the memory of Robert E. Lee, would resurface for modern readers. Du Bois’s masterful takedown of Lee, though written almost a century ago, has been circulating widely on social media. After conceding Lee’s military genius, Du Bois exposes the Confederate general’s moral failure with clarity and eloquence that make the essay arguably more relevant today than when it was written.

Lee’s moral failure, Du Bois explains, was not only his defense of slavery but also his failure to reject the narratives of the social hierarchy that surrounded him. He writes: “(Lee) followed Virginia not because he particularly loved slavery... but because he did not have the moral courage to stand against his family and his clan... He was asked to lead armies against human progress... and did not dare refuse.”

As Du Bois pointed out, standing up against the crowd is the real test of moral fortitude. One must have the backbone to oppose “the overwhelming public opinion of their social environment.”

This principle is no less true today, not only in reconsidering Lee and other historical figures (and monuments to them), but in many other areas of social discourse. Standing up against the crowd is difficult because it conflicts with deeply ingrained human impulses. As social animals, we have a tendency to conform to predominant beliefs and views within our social group, whether that group is our family, our close friends, our community, our school or work peers, or the broader society. Open dissent in any of these contexts can be difficult, escalating in intensity with the perceived importance of the challenged views within the group.

It’s easy to understand why such impulses would have had survival value for our ancestors. Individuals with personality traits that encouraged cooperation and cohesion would have often had an evolutionary advantage over those who reflexively challenged group decisions and viewpoints. These hard-wired impulses towards conformity and groupthink, meanwhile, explain why much of what we are taught as children encourages us to think and act as Lee did—to stand by our social group even when it marches us toward moral and human calamity.

From a young age, in various ways we are taught, encouraged, and sometimes even manipulated to accept all kinds of ideas—religious beliefs, political outlooks, nationalistic values, and views on matters from sex to immigration—that are predominant in our families and other social circles. As members of social groups, we are fed narratives that we are expected to simply accept. These narratives might address big theological questions or they might tell us what to think about people who don’t look like us. They might tell us how to think about long-dead warriors, but they might also tell us what to think about a war to be launched tomorrow.

Even if we have the intellectual independence to critically question such issues for ourselves, we might still hesitate to vocalize our opinions if they challenge the established position of a social circle that is important to us. As Du Bois teaches, and as Lee's failure shows, our own moral character depends on our ability to transcend such narratives and think for ourselves, to speak up when our critical thinking leads us to question the prevailing social structure.

Independent thinking might sound dangerous to some, as if it would necessarily overturn established morality. But that is hardly the case. A willingness to think independently does not equate to moral anarchy. Free thinking does not mean quickly jumping aboard every crazy idea that comes along to challenge established norms. Critical thinking does not require the rejection of long-accepted truths when those truths can be backed up by evidence.

But if a prevailing idea, belief, or practice can't stand up to scrutiny, it should be questioned if not outright opposed. In such a situation, human impulses toward moral cowardice are an obstacle to progress.