Decision-Making

How Being Rational Can Go Wrong

Good choices can create polarization and extremism.

Posted May 31, 2023 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- People on both sides of a political issue may make decisions rationally, yet they still become polarized.

- The most extreme or polarized people are often the least informed but still impact others most.

- We can reduce polarization and extremism if we re-frame decisions as assessment problems (how good is A / B?).

Whether deliberating about politics, the colors of a dress, or whether pineapple belongs on pizza, it’s hard not to be struck by how quickly and deeply people can become entrenched in their beliefs and opinions. The problem of polarization has infiltrated many aspects of our society, making it hard to find common ground, compromise with one another, or see things from the “other side.” In some ways, it is easy to attribute these divisions to psychological biases, misinformation, and echo chambers. Certainly, these contribute to the problem of polarization. A less comfortable idea, which I suggest is key to understanding polarization and extremism, is that many people–even those on the “other side”–act perfectly rationally and generally do their best to make informed decisions.

How could it be that outcomes like polarization and extremism come from good intentions? The answer is at the root of decision-making. To make good decisions, we must balance (at least) two factors: the amount of information we gather to make our decisions, and the amount of time we invest into deciding. Making a rational choice depends on balancing the importance of the decision against how careful we want to be while making it. It doesn’t make much sense to invest an hour into deliberating among laundry detergents, nor does it make sense to buy a house after only a few minutes of consideration. For some people, their time is more valuable, and for others, it’s important to have lots of information before they decide.

However, not all information is made equal. Some pieces of information are extremely persuasive, tipping us toward one option or another. Finding out that one candidate in an election has been embezzling money for decades might carry more weight in helping me decide who to vote for than, say, finding out one of them spends slightly more time watching TV every day. That means I’m more likely to stop and make my choice after considering an extreme or persuasive piece of information (e.g., embezzling) rather than a weak or moderate piece of information (e.g., watching more TV). When deciding, the extreme information is more useful in that it allows us to make up our minds quickly. Being rational, therefore, entails using extreme information to make fast choices.

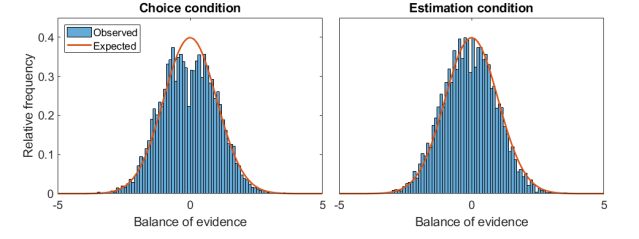

This idea–that rational decisions are made based on extreme information–is troubling. In a recent paper, my colleagues and I took a deep dive into the question of how people gathered information during decisions and how this related to polarization. We assigned people to one of two conditions: 1.) a “choice” condition where people were asked to gather information with the goal of deciding between two options, or 2.) an “estimation” condition where they were asked to gather information with the goal of estimating or evaluating the difference between the two options. They did this for a series of 80 different vignettes covering topics ranging from politically sensitive issues (weapon control) to health (disease control) and even mundane choices like which of two sites to mine for materials. These are the results:

People in the decision condition were over-sampling extreme information and ultimately became polarized. This corresponds to the sizable gap in the middle of the histogram on the left, which describes the distribution of beliefs that people had for a new issue on which they made a decision. The lack of people in the middle means there were fewer moderates than there should be, based on the true information “out there” available for consideration during their decisions. This effect was exacerbated when people gathered less information, such that people who prioritized time over accuracy had more extreme beliefs and became more polarized. This effect was also worse among people who were highly dogmatic (adhered to a rigid belief system) and intolerant of uncertainty (felt like they had to make up their minds).

The real problem comes from the fact that these polarized people were following completely rational strategies. They could justify their extreme positions by claiming they were entirely rational–and they might very well be right! Unfortunately, the situation gets worse before it gets better. Other work suggests that people with extreme positions but relatively little information also tend to be extremely confident in their views, carry greater sway over others, and form echo chambers that exacerbate polarization. As a result, the least-informed decision-makers tend to be the ones that become the most polarized and also the ones who carry the most influence in our culture.

It's not entirely doom and gloom in the land of rationality, though. You may have noticed that the participants assigned to our “estimation” condition don’t show the same pattern of polarization as the decision-makers. By focusing on estimating the difference between options, people reduce their reliance on extreme information. In fact, extreme information tends to be “noisy” and makes it hard to get a bead on exactly what the difference in quality between two options is, making it antithetical to good assessments. As a result, our estimators avoided becoming polarized. To the extent that we can encourage people to focus on assessing the degree of difference between candidates (or products, or positions, etc.), we should reduce the creation of polarization and extremism in the first place.

I hope there are a couple of take-home messages here. First, the people on the other side of an issue aren’t necessarily biased or irrational, and it is possible for two polarized people to have both followed a rational decision process to arrive at their diverging beliefs. Yet we should be careful of people with extreme views because chances are that they’re among the least well-informed on the actual issues. Finally, it’s worth trying to re-frame important decisions as assessment problems–think about the differences between your options rather than just choosing one. Doing so may make you part of the solution to polarization and extremism.

References

Kvam, P. D., Alaukik, A., Mims, C. E., Martemyanova, A., & Baldwin, M. (2022). Rational inference strategies and the genesis of polarization and extremism. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7344.

Navarro, D. J., Perfors, A., Kary, A., Brown, S. D., & Donkin, C. (2018). When extremists win: Cultural transmission via iterated learning when populations are heterogeneous. Cognitive Science, 42(7), 2108-2149.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1971). Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin, 76(2), 105–110.

Kashima, Y., Perfors, A., Ferdinand, V., & Pattenden, E. (2021). Ideology, communication and polarization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 376(1822), 20200133.