Resilience

What Erroneous Beliefs Do You Hold about Resilience?

New research on resilience around the globe

Posted May 30, 2017

What makes this word so tantalizing is that it is both profound and ordinary. Consider these two articles published in the New York Times over the past week:

Penguins Ride Maturity, Resilience Back to Stanley Cup Final [title of an article on whether the defending National Hockey League champions will win back-to-back titles]

There is no simple or single truth to be extracted from the Vietnam War. Many questions remain unanswerable. But if, with open minds and open hearts, we can consider this complex event from many perspectives and recognize more than one truth, perhaps we can stop fighting over how the war should be remembered and focus instead on what it can teach us about courage, patriotism, resilience, forgiveness and, ultimately, reconciliation. [final paragraph on the 40-year legacy of a war where hundreds of thousands of soldiers fought and died while a large minority of Americans at home offered a homecoming best described as contempt]

You might shudder at using the word resilient to describe athletes who ice skate for millions of dollars and 19-year old kids risking their lives to fight in a war they didn't understand or volunteer for to protect their nation from harm. This kind of comparison begs for a definition. Here is one of many crafted by psychologists:

With this definition in tow, who doesn't want to be resilient? What parent doesn't want to raise their children to be resilient?

The problem is not the definition. It is the quest to find an exact formula. Because none will be found. Being resilient doesn't mean being immune to negative feelings. Resilience often requires working through the emotional and physical pain of trauma, loss, and adversity.

A common societal belief is that we need to possess certain feelings. A particular frequency of positive emotions will offset stressful situations and with this formula, you can then be described as thriving or flourishing or happy. Several scientists have argued for an exact 2.9 positive emotions for every 1 negative emotion. The fact that this positivity formula has been debunked is of less concern than the amount of money, attention, and coaching or therapy sessions dedicated to getting people to change their feelings as a strategy to become empowered, happy, and resilient.

The quest for a resilience formula is part of a scientific fad of categorizing, labeling, and defining people in binary terms - are you part of the group that is flourishing in life? are you resilient? What this approach fails to acknowledge is that we do not just bounce back or remain at a lofty psychological state following adversity. Our hardships and pain change us. Our accomplishments change us. Can you ever go back to before the hardship? The parents whose child committed suicide. Rape survivors. The 19-year old Marine on the frontlines of war does not return to civilian life as the same person. What happens to us influences us.

Just as we will never get to stand up and proclaim, "I am now courageous or humorous or compassionate", resilience is a process, a journey, and not a definitive outcome.

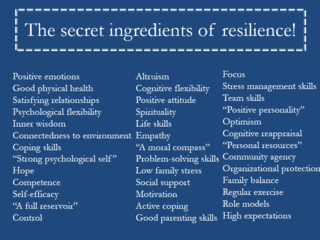

My colleagues and I have been skeptical of a large number of psychological traits that have been described as antecedents to resilience. A closer look at how these studies were conducted warrants skepticism. A large number of studies measure resilience as a personality trait that can be measured at one-time point with items such as " I usually come through difficult times with little trouble." Think about the mental gymnastics required to answer this one question. You must recall difficult times. You must remember who you were, what you did, and how you felt before each time. You must remember who you were, what you did, and how you felt after each time. You must contrast the two. And then you must make a mental comparison to some arbitrary reference point of whether the change that occurred can be construed as troublesome and if so, how much. You must do all of this while taking into account the retrospective bias of trying to view the world from how you felt before experiencing stress, strain, and difficulty. This is no small task to ask of anyone and keep in mind that this is usually one of a dozen questions being asked. Most people answer this question in 2-3 seconds. So should we trust this approach to studying resilience? My colleagues and I don't think so (read the work of Dr. George Bonanno who shares a similar view).

To avoid being hypocrites, we did something different. We defined resilience as the distress experienced in response to adverse life events over the course of 3 months. We explored change. We did not study a bunch of college student enrolled in a college course. We studied 797 adults from 42 countries and examined whether personality strengths deemed to be central to resilience such as grit and a sense of control truly matter.

We uncovered a very important storyline. How you study resilience matters. If you want to obtain erroneous results, ignore what people were thinking, feeling, and doing before an adverse, negative life event occurred. Seven out of seven personality strengths altered the influence of a negative life event on well-being. If you endorsed being a grateful person, a curious person, a gritty person, someone with a sense of control in life, you reported being less affected by negative life events. The dodo bird verdict prevailed. Every single personality strength provided a source of resilience.

But then we examined change. We accounted for people's psychological functioning before the adversity occurred to determine whether possessing personality strength led to resilience. Upon doing this, the storyline that psychological strengths confer resilience became a lot less promising. Grit failed to offer resilience. Curiosity failed to offer resilience. Having a sense of meaning and purpose in life failed to offer resilience. The only personality strength to predict a resilient trajectory was hope. What works about grit is not new (perseverance) and what is new about grit (consistency of interests) might be irrelevant to well-being and resilience.

Hope is about energetically pursuing one’s goals (agency) and being able to generate multiple strategies to devote effort and make progress (pathways). Essentially, Dr. Rick Snyder created an elegant formula:

Hope = Agency thoughts x Pathways thoughts

Granted, hope is a horrible term because it is not a synonym of optimism. But this theory of hope by Dr. Rick Snyder, and built on by Dr. Shane Lopez, is potent. Highly hopeful people are resilient to life's slings and arrows.

There is good reason to suggest that the most common reaction to adverse life events is resilience. Less is known about individual differences that increase

the likelihood of resilient responses. We will only learn about what makes people resilient and how to help people become more resilient with sufficient scientific theories and methodologies. Pay close attention to the next study on resilience. Pay close attention to the newspaper article or blog post that suggests the 10 ways to becoming resilient. Read the source studies. Because a lot of the work out there is using improper methods, drawing erroneous conclusions, and leading far too many people astray.

To read our latest study, download it here:

multiwave study. Journal of Personality, 85(3), 423-434.

****And a note of gratitude to readers who helped our latest book, The Upside of Your Dark Side, officially become a bestseller over the past month. Robert and I love to hear what helped people - do not hesitate to send us an email.****

Dr. Todd B. Kashdan is a public speaker, psychologist, professor of psychology, and senior scientist at the Center for the Advancement of Well-Being at George Mason University. His latest book is The upside of your dark side: Why being your whole self—not just your “good” self—drives success and fulfillment. For more, visit toddkashdan.com