Politics

Surveillance and Manipulation in the Internet Age

How psychometrics and data science were used to shape a presidential election.

Posted December 31, 2016

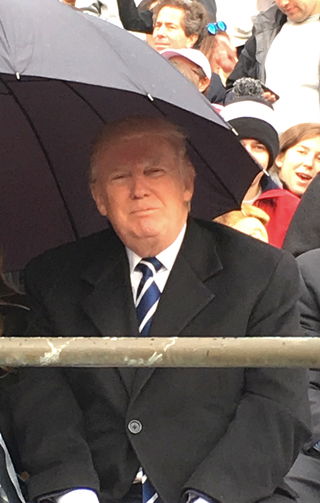

In the aftermath of the Clinton-Trump election, many are still struggling to come to terms with the final results. Donald J. Trump has been elected president, counter to the predictions of all leading pollsters and statisticians.

In one of the most read articles this year in the German press, Grassegger and Krogerus (2016) describe how the Trump harnessed the power of the Internet to influence voters and win the election. Here, I recap the most salient portions of this fascinating but frightening article for American readers.

Using big data to predict personality

Michal Kosinski, a Stanford professor, is a leading expert on psychometrics. He has published several articles on "Big Data," and the idea that everything we do, whether on the Internet or outside, leaves digital traces. Any purchase with a credit card, any Google request, any move with the cell phone in the pocket, each Facebook “Like” is saved. For a long time, it was not quite clear what these data should be good for. It was also unclear whether Big Data is a great danger or a big gain for mankind. Since Election Day we now know the answer, because behind Trump's online election campaign and also behind the Brexit campaign is one and the same Big Data company: Cambridge Analytica with its CEO Alexander Nix. Cambridge Analytica, based in the UK, is a privately held company that combines data mining and data analysis with strategic communication (read: covert online propaganda) for the electoral process. It was created in 2013 to influence American politics, and has been involved in dozens of US political races.

"We have psychograms of all adult US citizens – 220 million people." - Alexander Nix, CEO of Cambridge Analytica

In 2012, Kosinski proved that it is possible to predict, from an average of 68 Facebook “Likes,” a person’s skin color (95% accuracy), whether a person is LGBT (88% probability), and whether they are a Democrat or Republican (85%). But it goes even further: Intelligence, religious affiliation, alcohol, cigarette and drug consumption can all be calculated. This is where Cambridge Analytica steps in and puts to use precisely what Kosinski had demonstrated: "We have psychograms from all adult US citizens – 220 million people," Nix boasts. They have detailed personality profiles for each person that are not unlike Myers-Briggs style profiles, based on web pages visited, clubs, churches attended, educational attainment.

According to Nix, ”We're able to identify clusters of people who care about a particular issue, pro-life or gun rights, and to then create an advert on that issue, and we can nuance the messaging of that advert according to how people see the world, according to their personalities."

Cambridge Analytica's methods rely on machine learning, starting with a detailed survey, often presented as a psychological test. According to Sky News, Cambridge Analytica creates these and seeds them on Facebook, where they are filled in by hundreds of thousands of people (Cheshire. 2016).

Keeping Clinton voters away from the polls

Trump’s conspicuous contradictions, his often criticized attitude, and the immense number of different messages suddenly turned out to be his great advantage. Online, Nix can create a scenario where each voter sees only the message they want. "Trump acts like a perfectly opportunistic algorithm, which only depends on audience reactions," noted the mathematician Cathy O'Neil in August. On the day of the third presidential debate between Trump and Clinton, Trump’s team sent out 175,000 different variations of its arguments, mainly via Facebook. The messages differ only in microscopic details, to best suit the recipients’ psychological profile optimally: different titles, colors, subtitles, with photo or with video. The precision of the adaptation goes down to very small groups, explained Nix. "We can reach villages or blocks of houses in a targeted manner. Even individuals."

Almost all adult US citizens are on Facebook in some way. They might not have an account but unless a person takes some extreme and complex steps to block every single domain and IP address Facebook owns then they are still going to be accessing or using Facebook, even if they never directly visit Facebook.

In Miami's Little Haiti district, Cambridge Analytica provided residents with news of the Clinton Foundation's failure after the earthquake in Haiti – to stop them from choosing Clinton. This is one of the goals: for potential Clinton voters (this includes dubious leftists, African Americans, young women, people from the inner city), a Trump associate explains, "[we] oppress their choice.” In so-called “darkposts,” purchased Facebook advertisements in the Timeline, for example, African Americans see videos in which Hillary Clinton refers to Black men as predators.

The company divided the US population into 32 personality types, concentrating only on 17 battleground states. And as Kosinski had found that men who like MAC Cosmetics are very likely gay, Cambridge Analytica found out that a preference for US-made cars is the best sign of possible Trump voters. Among other things, Trump then is shown which messages are moving the people and where exactly it is happening the best. The decision to focus on Michigan and Wisconsin over the last few weeks was based on data analysis. With his victory in hand, the candidate becomes a model of the implementation of a model.

In light of this, one wonders how many of the decisions we make are our own, or if we are simply victims of an elaborate manipulation taking place behind the digital curtain.

References

Cheshire, T. (2016, October 22). Behind the scenes at Donald Trump's UK digital war room. Sky News.

Grassegger, V.H., & Krogerus, M. (2016, December 3). Ich habe nur gezeigt, dass es die Bombe gibt. Das Magazin, 48.

Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. & Graepel, T. (2013). Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110 (15), 5802–5805, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218772110

Sellers, F.S. (2015, October 19). Cruz campaign paid $750,000 to ‘psychographic profiling’ company. The Washington Post.