Trust

Negative Emotions May Make Us Trust Less

Understanding the impact of emotions on the neural mechanisms of trust.

Posted March 14, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Sometime in the autumn of 1861, Charles Darwin was having a bad day. “But I am very poorly today and very stupid and I hate everybody and everything,” he wrote to his friend. On days like that, Darwin concluded, “one lives only to make blunders.” Those days and those blunders are familiar to many. Most of us can recall one of our own bad days, when we sprayed our foul mood onto innocent bystanders and family members as an aftermath of an unpleasant occurrence that had nothing to do with them (the boss promoted someone else, the traffic was record-breaking, the wallet got lost, the favorite show ended).

As research attests, experiencing negative emotions can result in more than “hating everybody and everything.” Negative moods can impair our associative memory, alter our judgments of others by making us more prone to stereotyping and forming less favorable impressions, and even lead us to feel more pain. Negative emotions, it seems, may also make us more distrustful.

Negative emotions and trust

In a new study published in Science Advances, an international team of researchers from the University of Amsterdam and the University of Zurich set out to explore what effect negative emotions have on trust. Trust is among the most cardinal of social lubricants. From families to governments, it is deeply woven into the very fabric of human societies. Which makes it even more crucial to understand the mechanisms of trust – what feeds it and what erodes it. As new research shows, negative emotions might make us less trusting. Even if these emotions are incidental and are triggered by situations that are unrelated to our present circumstances.

The study

For the study, participants were invited to play the trust game in the MRI scanner. In this game, two players anonymously send money to each other from an endowment that they received from the experimenters. When the first player – the investor – sends a part of his endowment to the second player – the trustee – the invested money gets tripled (for example, if the investor invests $20 into the trustee, the trustee receives $60). The trustee, then, has the chance to send back to the investor any amount of money (including nothing at all) from his newly received sum.

The game has the potential to lead to monetary benefits for both players, if the investor trusts and if the trustee reciprocates. However, if the trustee does not reciprocate, then the initial trust of the investor will be betrayed. Thus, the investor faces a dilemma – investing can lead to more income (if the trustee is trustworthy) or a loss of his investment (if the trustee turns out to be untrustworthy). Importantly, the participants played the trust game in two conditions: while experiencing neutral emotions and while experiencing negative emotions. To induce negative emotions, the participants were faced with the threat of receiving unpleasant electrical shocks – a threat-of-shock method commonly and reliably used to induce anxiety in experiments investigating the effects of anxiety on cognition.

The results showed that when feeling anxious, the participants trusted other players much less and, hence, invested less of their money.

Why would our trust decrease when we are experiencing negative emotions?

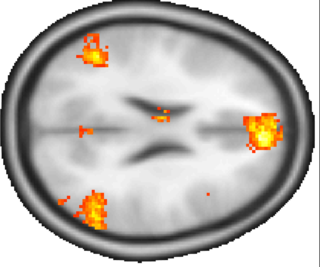

The answer may lie in the brain mechanisms of trust. As the study’s neuroimaging results demonstrate, the aversive emotions that the participants felt from the looming threat of electrical shocks suppressed the activity and connectivity of the brain’s “trust network” (a network of regions that displays stronger connectivity the more the participants felt trust). Originating in the temporoparietal junction (or TPJ), this network is thought to support social cognition and our ability to think about other people, their beliefs and their intentions.

These social abilities, sometimes referred to as “theory of mind,” are thought to be relevant when we are faced with trust decisions. Since anxiety disrupted the connectivity between TPJ and key regions for emotions and theory of mind (amygdala, DMPFC, right STS), it could have also affected the underlying mechanisms of trust and social decision-making.

For better or worse, our emotions color our everyday lives – how we behave, how we think, how we interact. As lead author of the latest study, Jan Engelmann, notes, negative emotions “can suppress the brain mechanisms crucial for understanding others.” This means that they may not only make us less trusting but may also affect “our willingness and ability to engage with others’ point of view,” according to Engelmann. Perhaps something worth keeping in mind next time you find yourself rummaging through your car for your lost wallet while being stuck in non-moving traffic on your way to an important encounter.

References

Bisby, J. A., & Burgess, N. (2014). Negative affect impairs associative memory but not item memory. Learning & Memory, 21(1), 21-27.

Bodenhausen, G. V., Sheppard, L. A., & Kramer, G. P. (1994). Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness. European Journal of social psychology, 24(1), 45-62.

Engelmann, J. B. (2010). Measuring Trust in Social Neuroeconomics: a Tutorial. Hermeneutische Blätter, 1(2), 225-242.

Engelmann, JB and Fehr, E (2017). The Neurobiology of Trust: the Important Role of Emotions. P. A. M. van Lange, B. Rockenbach, & T. Yamagishi (Eds.), Social Dilemmas: New Perspectives on Reward and Punishment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Engelmann, J. B., Meyer, F., Ruff, C. C., & Fehr, E. (2019). The neural circuitry of affect-induced distortions of trust. Sci Adv, 5(3), eaau3413.

Engelmann, Jan B., and Todd A. Hare. "Emotions can bias decision-making processes by promoting specific behavioral tendencies." (2018); in Davidson R.J., Shackman A., Fox A., Lapate R. (eds.), The Nature of Emotion; Oxford University Press.

Robinson, O. J., Vytal, K., Cornwell, B. R., & Grillon, C. (2013). The impact of anxiety upon cognition: perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 203.

Forgas, J. P., & Bower, G. H. (1987). Mood effects on person-perception judgments. Journal of personality and social psychology, 53(1), 53.

Wiech, K., & Tracey, I. (2009). The influence of negative emotions on pain: behavioral effects and neural mechanisms. Neuroimage, 47(3), 987-994.