Leadership

Lessons from Animals About Barriers to Female Leadership

A seminal new study points to reasons why females don't, but could, lead.

Posted October 9, 2018

"Despite many efforts to narrow the gender gap in leadership roles, women remain universally underrepresented in the top leadership positions in virtually every discipline, including in the sciences, politics and business. We were therefore interested in pursuing a non-traditional approach to understanding this phenomenon by looking for clues in societies of non-human animals."

"We have much to learn from the fascinating ways that natural selection has favored behavioral traits of non-human animals. By studying non-human mammals where female rule the roost, we may gain insights into secrets for smashing the glass ceiling."

I recently learned about a new research paper published in The Leadership Quarterly by Mills College biologist Dr. Jennifer Smith and her colleagues entitled "Obstacles and opportunities for female leadership in mammalian societies: A comparative perspective." I'd already read a short summary of this landmark study in a New Scientist piece titled "The 7 non-human mammals where females rule the roost," and was thrilled when Dr. Smith agreed to be interviewed about this detailed data-driven study that "elucidates barriers to female leadership, but also reveals that traditional operationalizations of leadership are themselves male-biased." Our interview went as follows.

Why did you and your colleagues conduct the research you did concerning female leadership in non-human mammalian societies? Can you please explain the importance of the comparative perspective for readers who don't know what this entails?

"...by studying the behavioral patterns of animals alive today, we hoped to understand the emergence of female leaders within a comparative evolutionary framework to offer insights into the value of as well as potential historical barriers to female leadership over millions of years across the mammalian lineage."

Despite many efforts to narrow the gender gap in leadership roles, women remain universally underrepresented in the top leadership positions in virtually every discipline, including in the sciences, politics, and business. We were therefore interested in pursuing a non-traditional approach to understanding this phenomenon by looking for clues in societies of non-human animals. Because natural selection is expected to favor solutions that permit individuals to succeed in their ecological circumstances, we expected to uncover the rules governing societies that promote, and thrive because of, strong female leaders. Thus, by studying the behavioral patterns of animals alive today, we hoped to understand the emergence of female leaders within a comparative evolutionary framework to offer insights into the value of as well as potential historical barriers to female leadership over millions of years across the mammalian lineage.

How did you collect and analyze the data?

We reviewed data for 76 social species of well-studied mammals for which patterns of leadership are understood across four contexts in which leadership occurs: movement, food acquisition, within-group conflict mediation, and between-group interactions. In a previous study called "Leadership in Mammalian Societies: Emergence, Distribution, Power, and Payoff" my colleagues and I identified these four domains as important for human and non-human mammalian societies, defining leaders as those individuals who impose a disproportional influence on the collective behaviors of group members. In the current study, we identified those species for which females consistently lead in conflicts lead more often than males in at least two of these major contexts. We used this strict definition of species with strong female leadership to learn about cases for which female leadership is the norm.

What are your major findings about the non-humans in which female leadership occurs?

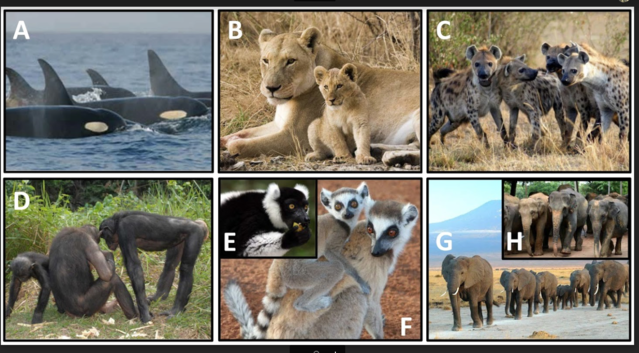

Based on our strict definition of “strong female leaders”, we found that female-biased leadership is generally rare in social mammals, but is pervasive in the lives of killer whales, lions, spotted hyenas, bonobos, lemurs, and elephants. Leaders emerge without coercion and followers benefit from the social support and/or ecological knowledge from elder females.

In your essay, you note seven observations that might be relevant to humans. Can you briefly explain each?

1. Female leaders most often emerged within families and small egalitarian groups, such as occurs in lions and elephants. This often occurs when adult females are followed by their dependent offspring. Although simply moving from place to place has often been viewed as a trivial process, females are key in moving groups away from danger and towards food, both of which are vital for survival. This is just one example of the many ways that female mammals influence societal outcomes in important ways that are often overlooked or otherwise underappreciated when viewed within the traditional operationalizations of human leadership.

2. Strong female leaders are more likely to emerge when females form cooperative units, such as occurs in bonobos and spotted hyenas. This pattern has obvious implications because it suggests that women are more likely to be successful leaders when forming strong coalitions within their social networks. Women may benefit from using social media and fostering coalitions of their own to form strong alliances resembling the boys' network in men.

3. Female elders often serve as important repositories of knowledge, leading group members to important food sources and away from danger. In orcas to elephants, we see a combination of a long lifespan and groups consisting of multiple generations of individuals belonging to the female lineage, including post-reproductive females with extensive knowledge.

4. Strong female leaders seem more likely to emerge in species for which conflict management within groups is vitally important, as occurs in spotted hyenas. This suggests a niche for women as leaders in organizations requiring conflict mediation within and between groups.

5. Many of the mammalian species with patterns of strong female leadership deviate from the typical mammalian pattern such that females are slightly bigger and stronger than males, either on their own, by joining forces with each other, or both. Spotted hyenas, for example, are physically larger than males. Female and male lemurs are the same size. In contrast, bonobos must join forces with other females to overcome their smaller size compared to males. With new technologies, humans are able to overcome these physical barriers, with virtual and in-person coalitions mobilizing and empowering women to overcome these potential barriers.

6. Some traits observed in mammals with strong patterns of leadership, such as a bias for female dispersal within human groups likely cannot explain the scarcity of female leaders in humans. We (humans) share 99% of our genes with bonobos and chimpanzees. Although both species resemble humans in that they also show patterns of female-biased dispersal, only bonobos have strong female leadership.

7. Our review has practical implications for women's leadership in modern business and politics. It suggests that some factors may be partly the result of evolved sex differences in physique and behavior but also that humans have the potential to overcome these obstacles.

You also note that possible "evolutionary obstacles" to female leadership in humans are not insurmountable. What are they and why do you think they can be overcome? I'm following up on this statement from your essay, "Taken together, our comparative analysis shows that there are several obstacles to leadership by women that are deeply rooted in the evolutionary history of mammals but that many possibilities for female leadership exist, including those that are often ignored within the operationalized definitions of leadership."

In the article, we state that, “As a cultural species, we humans are able to select for our own future, get rid of – if we want – glass ceilings and pyramids, and create the kinds of social structures that enable organizations to profit from the “female leadership advantage”. For me, this is the notion that cultural traditions of humans may shape opportunities for female leadership is very exciting and leaves me with a sense of optimism.

What do you see as important future research projects on this very important topic?

Important steps for this research are to communicate our findings with broad audiences so that others may learn more about the “nature” of leadership. We are currently working to broaden the scope of this research -- to include more information on different species -- and to place it into a quantitative framework to disentangle the effects of evolutionary history and current ecological factors in shaping the emergence of strong female leaders within mammalian societies.

Is there anything else you'd like to tell readers?

We have much to learn from the fascinating ways that natural selection has favored behavioral traits of non-human animals. By studying non-human mammals where females rule the roost, we may gain insights into secrets for smashing the glass ceiling. As humans, we possess the capacity to choose the ways we live, lead and help others. We may implement lessons we see as valuable and cast away those that we do not. Our study suggests that we may benefit from building support networks, learning skills from elder women in our communities, and managing conflicts effectively. Recognizing this is the first step towards promoting a more equitable society in which women are welcomed and supported as leaders. Our study suggests that not only is this a moral thing to do, but that supporting the emergence of women as leaders will benefit society as a whole.

Thank you, Jennifer, for such insightful and important answers. I believe your study will be a classic in the field and I hope it receives a wide readership not only among academics, but also among people outside of the biology arena, especially those in positions that could be used to balance the gender ratio among leaders in many different fields. The seven reasons you provide for why your study of non-humans is relevant to humans are right on the mark, and can surely serve as a launching pad that will benefit women in many different areas.

Note 1:

Non-human mammalian societies for which females emerge as strong leaders during collective behaviors across multiple contexts include: A) killer whales (Orcinus orca), B) African lions (Panthera leo; Photo by Greg Willis via Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 2.5), C) spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta; Photo by David S. Green), D) bonobos (Pan paniscus; Photo by Pierre Fidenci via Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 2.5), E) black-and-white ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata; Photo by Charles J. Sharp via Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0), F) ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta; Photo by David Deniss via Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0), G) African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana; Photo by Amoghavarsha via Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0), H) Asian elephants (Elephas maximus; Photo by Steve Evans via Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 2.0). All photos are public domain under the Creative Commons License except that used with permission of David S. Green.

References

Smith, Jennifer E., Chelsea A. Ortiz, Madison T. Buhbe, and Mark van Vugt. 2018. Obstacles and opportunities for female leadership in mammalian societies: A comparative perspective. The Leadership Quarterly.