Openness

The Knowledgeable Personality

General knowledge is most strongly related to openness to experience

Posted August 9, 2013

Individual differences in general knowledge about the world is a subject of particular interest to researchers in personality and intelligence. Some people have argued that having fundamental background information about one’s own culture is important to success in life (Gallo & Pickel, 2005). E.D. Hirsch coined the term “cultural literacy” to describe having this knowledge, and argued that comprehending written literature is very difficult without it. A number of studies suggest that students who possess adequate general knowledge required for cultural literacy have better educational and occupational outcomes than those who are less knowledgeable.

Knowledge Wins--American Library Association Advocacy during World War I

Some psychologists consider acquired knowledge as an important component of intelligence, particularly in adult life. The concept of crystallised intelligence explicitly includes how much information a person has acquired in their life, and a number of IQ batteries, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales include measures of general knowledge.

Although general knowledge is related to individual differences in intelligence, there is also evidence relating to differences in personality traits as well. A number of different studies have looked at correlations between general knowledge and personality traits, particularly those belonging to the Big Five model of personality. This model comprises the five broad traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. To the best of my knowledge, the correlations between general knowledge and big five personality traits have been reported in eight different papers, reporting the results of 10 different studies. (A detailed summary of the findings is provided in a table here, an earlier version of this article). One of these studies (Ackerman, Bowen, Beier, & Kanfer, 2001) examined only two of the Big Five (openness to experience and extraversion), whereas the remaining studies reported results for all five traits.

The trait most consistently correlated with general knowledge is openness to experience, which had positive correlations in all ten studies. Openness to experience is known to be positively correlated with measures of IQ and is characterised by intellectual curiosity and interest in learning. Hence its connection with general knowledge does not seem surprising. Findings in relation to other personality traits have been less consistent. Some researchers have proposed that extraversion (Ackerman, et al., 2001) and neuroticism (Chamorro-Premuzic, Furnham, & Ackerman, 2006) would be negatively correlated with general knowledge. Extraverted people with strong social inclinations might invest less time in non-social activities associated with learning. High neuroticism is associated with test anxiety and hence with poorer performance on ability tests. Others (Furnham & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2006) have argued that conscientiousness might have a relationship with general knowledge, although whether this should be positive or negative is unclear. Research has found that conscientiousness has a modest negative relationship with intelligence, hence people high in conscientiousness might be less knowledgeable. On the other hand, students high in conscientiousness achieve higher grades than their less conscientious counterparts and might be expected therefore to learn more. However, extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness have had inconsistent correlations with general knowledge across the studies I have reviewed, as there is a mixture of positive and negative correlations for each of them.

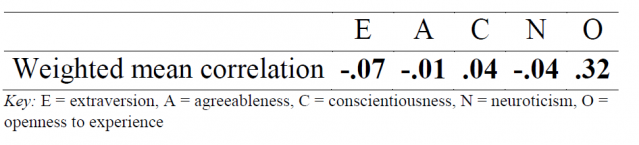

In order to obtain a more accurate estimate of the true correlations between each of the five personality traits and general knowledge, I computed a weighted average of the correlations for each study taking into account the sample size.[1] The total number of participants for all ten studies was 1786, for the nine studies examining all of the Big Five (this excludes Ackerman et al.) it was 1466. The results are shown in the table below.

Personality correlates of general knowledge

Openness to experience is the only personality trait with a substantial correlation with general knowledge. Correlations of about .30 are generally considered to be of moderate strength, although it has been suggested that they are actually large compared to most effects found in psychology studies (Richard, Bond Jr., & Stokes-Zoota, 2003). Extraversion and neuroticism had quite small negative correlations. These are in the direction predicted by Ackerman et al. (2001) and Chamorro-Premuzic et al. (2006) but the effect sizes are much smaller than expected. Conscientiousness has a very small positive effect, suggesting that it tends to be an inconsistent predictor at best. The effect of agreeableness is negligible.

Nine of the ten studies used tests designed to assess knowledge in a wide spectrum of non-specialist domains. However, the study by Ackerman et al. assessed more specialised forms of knowledge, specifically from 19 domains of academic study encompassing sciences, humanities, and civics. In this study, general knowledge was defined as a composite of these 19 domains. From this it appears that the “general knowledge” assessed in this study was of a more specialised and advanced type than that tested in the other nine studies. Interestingly, the correlation found for extraversion in the Ackerman et al. study was substantially larger (r = -.24) than the correlations for extraversion in the other nine studies. When I excluded this study from my analysis, the weighted mean correlation between extraversion and general knowledge became almost negligible (r = -.02), whereas the correlation between openness to experience and general knowledge barely changed (r = .31).

These results indicate that as far as the Big Five are concerned, characteristics associated with openness to experience, such as general curiosity and enjoyment of the life of the mind, are the most relevant to how much knowledge of the world a person acquires. Traits such as sociability (extraversion), emotional stability (low neuroticism), and achievement orientation (conscientiousness) appear to be much less important. When considering the findings of the study by Ackerman et al., it seems possible that extraversion might be unrelated to relatively non-specialised forms of knowledge, but becomes somewhat more important when considering more advanced levels of knowledge usually acquired with special study. That is, people who are highly extraverted may have as much non-specialist knowledge as the average person, but acquire less knowledge at a university level than their more introverted counterparts. Studies comparing non-specialist and more advanced forms of knowledge within the same samples would help to resolve this issue.

Results from quite a number of previous studies found substantial gender differences in general knowledge, with men tending to have greater knowledge than women (e.g. Ackerman, Bowen, Beier, & Kanfer, 2001; Furnham, Christopher, Garwood, & Martin, 2007; Gallo & Pickel, 2005; Lynn, Irwing, & Cammock, 2002). The results presented here would suggest that the reason for gender differences in general knowledge probably lie outside the big five personality traits. Women tend to score higher than men in neuroticism and to a lesser extent extraversion and conscientiousness (Schmitt, Realo, Voracek, & Allik, 2008) but the correlations between these traits and general knowledge appear far too small to account for the substantial gender difference in general knowledge. Furthermore, men and women do not tend to differ on their overall scores on openness to experience.

Openness to experience is usually considered to consist of a number of narrower facets, including openness to ideas, values, feelings, aesthetics, actions, and fantasy. There is evidence that men tend to be higher on openness to ideas whist women tend to be higher on openness to feelings (Schmitt, et al., 2008). Whether or not openness to ideas is more strongly related to general knowledge than the other facets has never been examined. Openness to ideas has a very strong conceptual similarity to a construct called typical intellectual engagement (Mussell, 2010). A number of studies (Chamorro-Premuzic, et al., 2006; Furnham, et al., 2009; Furnham, et al., 2008) found that typical intellectual engagement had positive correlations with general knowledge. However, a study by Furnham et al. (2008) found that overall openness to experience was a stronger predictor of general knowledge than the narrower trait of typical intellectual engagement. This finding might indicate that the broad tendency to be open to new experiences generally, rather than a specific facet of openness, supports the acquisition of general knowledge. In a previous post I argued that gender differences in general knowledge may be related to a greater male interest in things as opposed to a greater female interest in people. Elsewhere I have suggested that gender stereotypes could play a role as well. Future research could explore the respective contributions of gender typical interests, stereotypes, and possible differences in openness facets to sex differences in general knowledge.

Please consider following me on Facebook, Google Plus, or Twitter.

© Scott McGreal. Please do not reproduce without permission. Brief excerpts may be quoted as long as a link to the original article is provided.

Image credit: Musgo Dumio_Momio courtesy of Flickr

Other posts discussing intelligence related topics

What is an Intelligent Personality?

Emotional intelligence is not relevant to understanding psychopaths

Why there are sex differences in general knowledge

Personality, Intelligence and “Race Realism”

Intelligence and Political Orientation have a complex relationship

Think Like a Man? Effects of Gender Priming on Cognition

Cold Winters and the Evolution of Intelligence: A critique of Richard Lynn’s Theory

The Illusory Theory of Multiple Intelligences – a critique of Howard Gardner’s theory

More Knowledge, Less Belief in Religion?

References

Studies considered in my analysis are marked with a *

*Ackerman, P. L., Bowen, K. R., Beier, M. E., & Kanfer, R. (2001). Determinants of individual differences and gender differences in knowledge. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(4), 797–825. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.93.4.797

*Batey, M., Furnham, A., & Safiullina, X. (2010). Intelligence, general knowledge and personality as predictors of creativity. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(5), 532-535. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.04.008

*Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Furnham, A., & Ackerman, P. L. (2006). Ability and personality correlates of general knowledge. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(3), 419-429. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.036

*Furnham, A., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2006). Personality, intelligence and general knowledge. Learning and Individual Differences, 16(1), 79-90. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2005.07.002

*Furnham, A., Christopher, A. N., Garwood, J., & Martin, G. N. (2007). Approaches to learning and the acquisition of general knowledge. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1563-1571. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.013

*Furnham, A., Monsen, J., & Ahmetoglu, G. (2009). Typical intellectual engagement, Big Five personality traits, approaches to learning and cognitive ability predictors of academic performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 769-782. doi: 10.1348/978185409x412147

*Furnham, A., Swami, V., Arteche, A., & Chamorro‐Premuzic, T. (2008). Cognitive ability, learning approaches and personality correlates of general knowledge. Educational Psychology, 28(4), 427-437. doi: 10.1080/01443410701727376

Gallo, N. C., & Pickel, K. L. (2005). Undergraduates' General Knowledge. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Chicago. http://kpickel.iweb.bsu.edu/Gallo_Pickel(2005).pdf

Lynn, R., Irwing, P., & Cammock, T. (2002). Sex differences in general knowledge. Intelligence, 30(1), 27-39. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2896(01)00064-2

Richard, F. D., Bond Jr., C. F., & Stokes-Zoota, J. J. (2003). One Hundred Years of Social Psychology Quantitatively Described. Review of General Psychology, 7(4), 331-363. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.7.4.331

*Schaefer, P. S., Williams, C. C., Goodie, A. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2004). Overconfidence and the Big Five. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(5), 473-480. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.010

Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can't a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 168-182.

Note

[1] This is based on the theory that larger sample sizes should be given more weight as they are more likely to provide an accurate estimate than smaller samples. When the results were compared to the unweighted mean correlations there was very little difference between the results.