Anthropomorphism

The Peculiar Thought We Often Have When Facing Illness

Research explains a more curious aspect of the psychology of illness.

Posted May 27, 2016

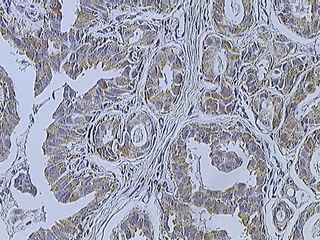

In the middle of my PhD, I was diagnosed with kidney cancer. There were many psychologically interesting and rich things that happened after my diagnosis, but one was especially peculiar: I began to anthropomorphize. Almost as soon as I learned of my cancer, I saw it as an agent, with goals and intent. And I saw each of the cancerous cells as its foot soldiers, on a mission to conquer my organs. Even friends and family referred to my tumor as an entity with evil aspirations- “that thing doesn’t know we are coming for him,” a friend said before my treatment.

This of course is just a single anecdote, but it alludes to an at once natural and entirely strange aspect of human cognition. In fact, research suggests that the tendency to anthropomorphize is fairly common. In the 1940s, at the dawn of social psychology as we know it today, the psychologists Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel conducted a study, showing that participants readily attributed goals, emotions, and intent to a series of shapes depicted in a short film clip.

And this recent IKEA commercial hinges on the same tendency to assign feelings and emotions to inanimate objects.

Why do we so readily think in these terms? The scientific literature offers a few reasons, but one is that anthropomorphism helps us make sense of a complex world. We ground what we might not fully understand in terms with which we are already very familiar. I wasn’t a medical doctor or an oncologist, so the easiest way for me to make sense of my cancer was to think of it through the lens of human behavior.

Anthropomorphism also helps us reduce uncertainty, and the anxiety associated with uncertainty. When I thought of my cancer as a human-like agent, I was able to use the template of human experience to make predictions about what it might do next.

Together, such findings suggest that anthropomorphism actually functions as a coping strategy, useful as we confront life's challenges. And in the aftermath of a life-altering diagnosis, it might be palliative, helping us restore a sense of order and predictability in our lives.

Of course, one of the interesting features here is that anthropomorphism tends to be a spontaneous process- a heuristic for making sense of what might otherwise seem unthinkable. And psychologists have developed a very robust literature centered on the idea that we have two ways, or systems, of thinking: a "quick and dirty" system, which makes use of heuristics and other mental shortcuts, and a second system, which engages in slower, conscious, and more effortful reasoning.

We might think of anthropomorphism as a coping strategy that falls under the purview of the first system. In the next post, I'll discuss another way of thinking about illness, which differs from anthropomorphism in two respects. First, it is a more deliberate process. And second, it involves adopting a more objective, "birds-eye" view of one's challenges. I'll also discuss how personality might predict which of these two strategies is most beneficial in any particular instance. Stay tuned!

--

Follow me on Twitter: twitter.com/sccotterill2

--

Heider, F., Simmel, M. (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. American Journal of Psychology, 57, 243–259.

Epley, N., Waytz, A., Cacioppo, J.T. (2007). On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114 (4), 864-886.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

(C) Sarah Cotterill. All rights reserved.