Meditation

A Meditation on Time and Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Jewish New Year

What do Rosh Hashanah and RBG have to do with the human condition?

Posted September 19, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Every cultural tradition offers signposts and prescriptions for collectively marking and emotionally processing the passage of time. This day, which by tradition begins this year at sunset on September 18, commences the 10-day process prescribed by Jewish tradition to mark the end of one year and the beginning of another.

Jews are called upon to review their lives of the past year and to imagine themselves as seated before a heavenly judge having open before them a book in which they will, within this 10-day period, decide the fate of each of us mortals for the year ahead: “who shall live and who shall die, who after a long life and who before her time, who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by beast, who by famine and who by thirst, who by upheaval and who by plague.”

To those who grew up in late 20th-century America, awake to the world of science that informed us that such an anthropomorphized judge on high was at the very least an extreme improbability, and in a milieu in which medical and technological progress appeared to have made deaths by water, fire, upheaval, and plague seem about equally improbable, at least in America, the words had a decidedly archaic ring to them. Yet nothing about modern scientific progress has erased the fact that we become a little older every year, that our time here is quite finite. “A human life is like grass. We bloom for a day. A wind comes, and then we vanish.” “Teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom.”

Are we post-moderns too cynical or simply too frazzled by the constant bombardment of information and competing messages to learn anything from these ancient admonitions?

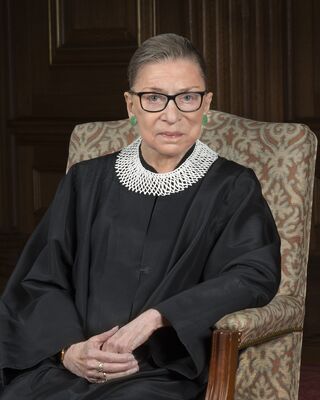

Yesterday, happenstance, or God (if one likes), sent a wind that took a magnificent flower that had bloomed, a towering figure in American jurisprudence, an inspiring champion of right, and by chance the first female Supreme Court justice of humble American Jewish origin, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. It was as if, when the Book of Life was being sealed at the end of those 10 days of reckoning now a year behind us, the “Holy one of Blessing” (as my own congregation refers to its deity) had decided that this was fated to be a year of reckoning for our entire species, and that one more 365 day year could be granted to the valiant Justice Ginsburg, but not a single day more.

Cognitive science teaches us that perception is a function of contrast. We notice and record what departs from what we had expected, feeling excitement, elation or happiness at tastes, sensations, kind words, fortunate events, that come as more than what we had felt we could count on, and feeling pain, disappointment, shock or grief at things we had hoped could be avoided or put off. We notice the passage of time only by those occasional shocks of novelty: that our children are suddenly adults, that our bodies are not what they had been, we have our first gray hair or maybe our first heart attack, or we learn that a friend of the same age or younger is suddenly gone.

Watching the short documentary on RBG’s life viewable at the New York Times website last night, I saw the innocent Brooklyn child become a determined young woman lawyer, a mature lawyer accepting her nominations to be an Appeals Court judge and then the second female justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and minutes later, the somewhat stooped and elderly but more determined than ever RBG pictured in real life and on tens of thousands of T-shirts.

That a person with such an acute mind and so deep a commitment to the highest values of our society can have been with us last week and be gone today illustrates well that that seemingly archaic notion that “a wind comes, and then we vanish” is not really so archaic after all. These past 365 days have also sadly shown us more than enough instances of some among us dying by water and others dying by fire, far too many dying not by the sword but by gunshot, suffocation, and brutality at the hands of police officers, and we’re witnessing plenty of upheaval and approaching 200,000 dying by a modern plague, Covid-19.

“Teach us to number our days” is on the one hand an appeal for being conscious of the preciousness of each moment in which we're able to experience the miracle of inhabiting a body and having the means to perceive the beauty of nature, the companionship of our friends and family, the joy of life and health. We can also feel joy and appreciation for the amazingness of our universe, the extraordinary progress our species is achieving decade by decade in its ability to comprehend that universe with our intellects, and with the ever-expanding kit of tools that, a week ago, allowed scientists to measure gravitational waves reaching Earth today from a collision of black holes that occurred seven billion years ago.

But "Teach us to number our days" is also an appeal to use our time wisely, to shoulder our responsibility to help to repair the world. As a much-quoted saying in the rabbinical text Pirke Avot puts it: “It is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but neither are you free to desist from the task.” RBG’s was an inspiring life lived to the last moment in a crusade for justice. You need not agree with all of her views, but if you can recognize and honor a life of purpose, of ideals, and of dedication, and try to live even one day of your year as she lived each and every day of her years while battling an unrelenting series of health crises with an inspiring determination to persist, you’ll do honor to your humanity.