Forgiveness

Good Mood, Bad Mood? Blame the Bacteria You Eat

The importance of gut bacteria in determining your emotional moods.

Posted December 15, 2017

What makes a person human? People have asked this for millennia. But time and again the answer evades us. It is neither our use of tools or language, our penchant for building societies, nor even sex. Perhaps human cells are the only marker of who we are and why.

Or perhaps not. New studies find that the bacteria in our gut—constituting one’s so-called microbiome—play a huge role in determining our emotions.

Comparing fecal samples along with brain images from 40 healthy adults, gastroenterologists at UCLA discovered that those with a greater abundance of a bacterial genus called Bacteroides differed in brain composition compared to those with the more common Prevotella genus of bacteria [1]. Though both strains are known as “good bacteria” that keep the body healthy, the two appear to affect the way brains grow and assimilate the outside world.

Subjects who harbored more Bacteroides showed thicker grey matter in the frontal cortex, insula, and hippocampus, regions that help regulate mood. Those with higher levels of Prevotella showed lower brain–tissue volumes in these areas, but greater connections among emotional, attentional, and sensory circuits. They reported higher levels of anxiety, distress, and irritability, too, when confronted with negative images—all conventional signs of less hippocampal control. A smaller hippocampus, the researchers hypothesize, could render a person more susceptible to wayward emotional triggers.

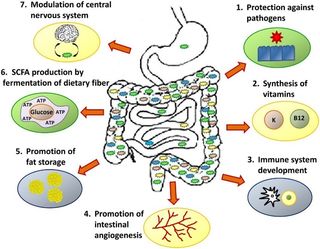

The correlation between gut bacteria and mood lies in the connection between the two brains we have: the familiar one in our heads, and the other in our guts. Often referred to as the “second brain,” our guts do more than turn food into energy: they make up an entire ecosystem of neurons and bacteria, both of which communicate with each other and with our head brain [2].

This “enteric nervous system” gives rise to nervous butterflies or a pit in your stomach during times of stress. Up to 90 percent of the cells in our digestive track convey information to the brain rather than receiving signals from it, making what happens in your gut perhaps more influential to your mood than your head is.

This might explain why individuals with different gut biota have observably different brains, at least as determined by today’s scanning methods. Because gut bacteria send signals directly to the brain, they may very well influence how brains take shape during development. Researchers are only beginning to understand the nuances of this influential relationship.

Unlike the rest of our cells, our microbiomes change frequently. A healthy human gut is home to at least 1,000 different species of bacteria, all of which are affected by what we eat, where we live, and whether we take antibiotics. Research shows that those whose diets are high in protein and animal fats harbor primarily Bacteroides bacteria, while Prevotella dominates in those whose diet is high in carbohydrates and fiber [4].

Rushing to stock up on steak would be premature. After all, fermented and fresh plant foods such as sauerkraut and berries are important to a healthy microbiome. Some even advocate vegetarianism as the ideal for maintaining ideal microbial health. Defining the connections between lifestyle, gut bacteria, and moods is a recent endeavor, and figuring out the details will undoubtedly take time. One thing is clear, though: “You are what you eat,” has never seemed truer.

References

[1] Tillisch, Kirsten, et al. Brain structure and response to emotional stimuli as related to gut microbial profiles in healthy women. Psychosomatic Medicine. June 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000493

[2] https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-fallible-mind/201701/the-pit-i…

[3] Amon, Protima, and Ian Sanderson. What is the microbiome? BMJ Journals. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-311643

[4] Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, Sinha R, Gilroy E, Gupta K, Baldassano R, Nessel L, Li H, Bushman FD, Lewis JD (October 7, 2011). "Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes". Science. 334 (6052): 105–8. PMC 3368382 Freely accessible. PMID 21885731. doi:10.1126/science.1208344.