Free Will

Do Longer Exhalations Affect Free Will Before Taking Action?

Exhaling may trigger the brain's readiness potential before a voluntary action.

Posted February 10, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Researchers at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have identified a link between the exhalation phase during a breathing cycle and a spike in "readiness potential" brain activity moments before a voluntary action.

This research suggests that humans may be more likely to initiate voluntary actions as they exhale and less likely to do so during the inhalation phase of the respiratory cycle. These findings (Park et al., 2020) were published on February 6 in the journal Nature Communications.

Readiness potential or "RP" is a brain signature observed in the human cerebral cortex just before someone makes a voluntary muscle movement. Because an uptick in RP occurs milliseconds before someone is about to make a voluntary movement, readiness potential is correlated with acts of free will.

Olaf Blanke, who is the senior author of this paper, speculates that our free will may be more affected by interoceptive signals related to breathing than previously recognized. The EPFL news release for this study is titled "Breathing May Change Your Mind About Free Will." The teaser for this article says:

"[Our] scientists have discovered that the readiness potential (RP) is coupled to breathing and that acts of free will happen as you exhale. The results suggest that the origin of the RP is linked to breathing, providing a new perspective on experiences of free will: the regular cycle of breathing is part of the mechanism that leads to conscious decision-making and acts of free will. Moreover, we are more likely to initiate voluntary movements as we exhale."

This research suggests that the push-pull between inhalations and exhalations may affect how someone unconsciously prepares to make voluntary actions. The authors propose that readiness potential "at least partly reflects respiration-related cortical processing that is coupled to the onset of voluntary action."

"More generally, [this research] further suggests that higher-level motor control, such as voluntary action, is shaped or affected by the involuntary and cyclic motor act of our internal body organs, in particular the lungs," first author Hyeongdong Park said in the news release.

"That voluntary action, an internally or self-generated action, is coupled with an interoceptive signal, breathing, may be just one example of how acts of free will are hostage to a host of inner body states and the brain's processing of these internal signals," Blanke added. "Interestingly, such signals have also been shown to be of relevance for self-consciousness."

In this two-minute YouTube video, Hyeongdong Park and Olaf Blanke recap their recent study.

Did Longer Exhalations Unwittingly Fortify My Free Will as an Ultra-Endurance Athlete?

For the second part of this post, I'm going to shift gears and filter the new research on a possible link between exhalations and free will through the lens of my life experience as an athlete. Over the years, I've written about how longer exhalations are an easy way to hack the vagus nerve. I've also shared childhood anecdotes about how my neuroscientist father, Richard Bergland, M.D.—who wrote The Fabric of Mind and was a nationally ranked tennis player—taught me to consciously extend the duration of my exhale in the milliseconds before serving a tennis ball.

When I started playing tennis competitively in the early 1970s, the idea of a mind-body connection that tied breathing techniques to the "relaxation response" was still a novel concept in Western culture. Coincidentally, during this era, my father worked at Harvard Medical School's Beth Israel Hospital and was colleagues with Herbert Benson, whom many credit with teaching a large general audience about the day-to-day benefits of mindfulness meditation practices rooted in breathing exercises.

As a neurosurgeon, my father learned through trial and error that taking a deep belly breath (inhalation) followed by a long, slow exhale gave him a steadier hand and better dexterity while performing brain surgery in an operating room.

He also identified the value of incorporating breathing exercises into his pre-serve routine on the tennis court. Before every serve, he'd bounce the ball four times and take a diaphragmatic breath followed by a long, slow exhale as he visualized serving an ace. As my tennis coach, Dad taught me these techniques.

At the time, my father's theory was that a long, slow exhale squirted out some "vagusstoff" (vagus nerve substance) on-demand, which acted like a tranquilizer that instantly slowed heart rate and calmed the autonomic nervous system. As a young tennis player, I was taught that one long exhalation before every serve was key to maintaining grace under pressure during tough matches.

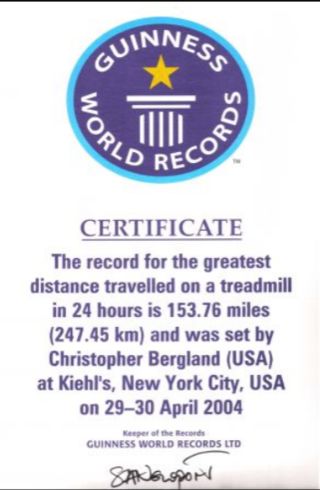

Many years later, when I became an ultra-endurance athlete, I applied the same breathing techniques I mastered on the tennis court to optimize my psychophysiological performance as an Ironman triathlete and ultra-marathon runner.

Until reading the new study from EPFL on exhalations being coupled with readiness potential, voluntary movements, and acts of free will, it never crossed my mind that the frequency and duration of exhalations might influence free will.

However, with hindsight, it seems possible that one reason I had an abundance of free will to voluntarily run, bike, and swim extreme distances may be linked to the fact that I've always focused on extending the duration of my exhalations before making important voluntary actions both on and off the court.

During a long, slow exhalation phase, my mind's eye visualizes, strategizes, and pre-plans future movements more effectively than if my breathing is quick and shallow. Based on these anecdotal observations, it seems possible that longer exhalations may optimize the brain's readiness potential before any voluntary action that requires lots of free will.

To be clear, the latest research (2020) by Park et al. on breathing being coupled with voluntary action and cortical readiness potential does not assert that longer exhalations boost free will. That said, it would be interesting if future research explored a possible association between longer exhalations and increased free will.

References

Hyeong-Dong Park, Coline Barnoud, Henri Trang, Oliver A. Kannape, Karl Schaller & Olaf Blanke. "Breathing Is Coupled with Voluntary Action and the Cortical Readiness Potential." Nature Communications (First Published: February 6, 2020) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-13967-9