Neuroscience

Mastering a Mindset of Loving to Win Without Hating to Lose

The upsides of loving to win without (really) hating to lose in life and sport.

Posted September 22, 2018

Heraclitus (c. 540-480 BC) famously said, “The road up and the road down are one and the same.” This aphorism sums up a pre-Socratic philosophy that everything is tied to an opposite that "it" depends on for existence (e.g., hot/cold, pleasure/pain, happy/sad, love/hate, win/lose, etc.) Some call the harmony of coexisting polar opposites the “unity of opposites.” The essence of this ancient Greek concept is also captured in the yin-yang symbol of Eastern philosophy. Within the two paisley-shaped waves of perfectly balanced black and white, there is a circular dot of the opposite, which creates equal dualities where dark and light each contain a seed of the other.

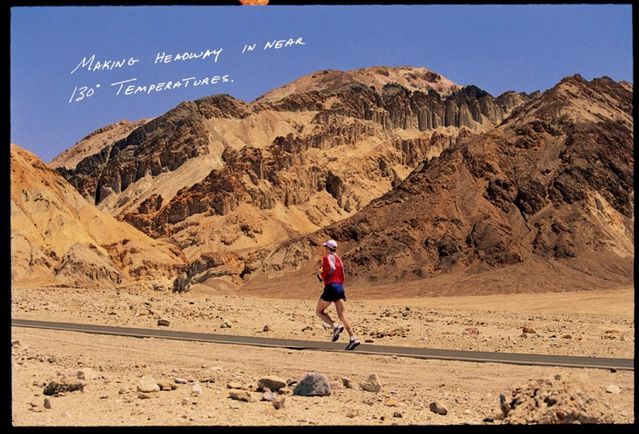

As an ultra-endurance athlete, this overarching philosophy helped me create an explanatory style that automatically reframed less-than-ideal circumstances in a positive light without being a Pollyanna. For example, if my feet were covered in blisters and I was consumed by the blackness of pain—but still had miles to run—I would look for a singular bright spot, focus my attention there like a laser, and keep jogging. It could be something awe-inspiring in nature, a smell, the line from a song, reciting a poem, or humming a melody.

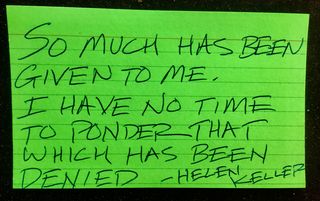

Over the years, I also learned through trial-and-error that putting myself in the shoes of someone else by memorizing quotations was an easy method of ego-transcendence. I'd transcribe these quotes onto note cards and kept them in big stacks on my nightstand. I'd flip through the quotes before falling asleep and committed them to long-term memory. The language got woven into my dreams and would pop into my head during the day whenever my subconscious realized that I needed some outside inspiration.

Using this “theory of mind” technique of putting my novel circumstance in a bigger and more timeless context helped me avoid feeling sorry for myself or getting stuck in a “woe is me” loop of rumination. On the flip side, if I ever started to become hedonistic or felt hubris creeping in after winning an event, I'd temper this fleeting "king of the world" feeling with a healthy dose of humility by raising the bar and challenging myself to do something slightly out of reach.

Upping the ante would inevitably require failing again; I like struggling to push beyond my comfort zone and taking chances more than resting on my laurels and playing it safe. Additionally, the key to creating a state of flow or superfluidity involves honing in on a sweet spot where your level of skill just barely matches the degree of challenge and then constantly raising the bar as your level of mastery and skill gets better.

Anytime I stumbled on a quotation that captured a nugget of wisdom related to coping with the spectrum of emotions and the high-wire act of finding a dynamic equilibrium between the “thrill of victory” and the “agony of defeat,” I’d jot the words down on a green fluorescent note card. For example, Helen Keller framed the hardship of not being able to see or hear by saying, “So much has been given to me, I have not time to ponder over that which has been denied.” If I was suffering from a muscle cramp in the lava fields during the Hawaii Ironman World Championships in Kona or during the Badwater Ultramarathon in Death Valley, I’d recite Keller's words to put my temporary and extremely privileged pain in perspective as I charged ahead, with a bit of a hobble.

Whenever I didn't win a big race (which happened all the time), I’d recite the Winston Churchill & Abraham Lincoln attributed concept of “Success consists of going from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm.” Then, I'd dust off any feelings of disappointment and begin strategizing my game plan for a comeback and specific ways to do better next time.

At every starting line, I’d recite a few lines from the Alice Walker poem, “Expect Nothing,” which was a touchstone in terms of navigating the tightrope of wanting to win so badly, but letting losses roll off my back without feeling gypped. Walker writes, “Expect nothing. Live frugally on surprise. Wish for nothing larger than your own small heart or greater than a star. Tame wild disappointment with caress unmoved and cold.”

I first glommed on to the paradoxical notion of "expecting nothing and everything at the same time" without becoming too cynical or unrealistically optimistic as an adolescent in high school. At the time (early 1980s), I was trapped at a stodgy and elitist boarding school in Connecticut. As a gay teen, it was obvious that I wasn’t “entitled” to the same societal perks as my straight peers; there’d be no invites to join the “old boys' club" after graduation if I ever came out. I let go of all expectations, which was a blessing in disguise. (For more strategies on dealing with a lack of cheerleaders in your life during high school check out, "Flip the Script: Morphing Naysayer Put-Downs into Motivation.")

The good news about being an outsider is that because I identified more with marginalized groups than so-called “masters of the universe,” there was no way I’d stay in the closet just to be accepted into their clique. And the process of coming out forced me to embrace iconoclasm without an ounce of sour grapes. Part of my psyche thrived on being an underdog and the psychological acrobatics and scrappiness of finding ways to cope with adversity via a fluid “unity of opposites” mindset.

A few weeks ago, I read about a neuroscience-based study on the benefits of loving to win (but not really hating to lose) that reminded me of "unity of opposites" and some of the tricks I used as an athlete and high school student to maintain a balanced approach to victory/defeat and being accepted/rejected. This paper, “Ventral Striatal Function Interacts with Positive and Negative Life Events to Predict Concurrent Youth Depressive Symptoms," was published online July 30 in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging.

At first glance, I wasn’t interested in reporting on this study primarily because on the surface it inadvertently seemed to promote a black and white concept of “winning” and “losing.” In a win-at-all-costs era filled with lots of high ranking people in positions of power who are all too quick to label others “winners” and “losers,” I wasn’t interested in unpacking the benefits of "loving to win." But, something about this study got stuck in my craw, and I found myself thinking about the more nuanced message of the brain benefits of loving to win whenever I was out for a jog or daydreaming. This morning, I decided to go back and do a deeper dive into what the researchers discovered and write this blog post.

Regarding the upsides of loving to win without (really) hating to lose mentioned in the subtitle, the researchers identified that having a robust brain response to winning was linked to (1) being more receptive to positive life experiences and (2) less prone to depression.

"This finding helps refine our understanding of how two types of known risk factors for depression, life events exposure and neural response to wins and losses, might interact to influence depression," first author Katherine Luking of Stony Brook University said in a statement. "This study is novel in that we go beyond negative events to investigate the unique effects of both positive and negative life events on depressive symptoms during a vulnerable time in development, early adolescence."

Based on a cohort of adolescent girls, the researchers found that those with a stronger brain response to winning something randomly also tended to reap the psychological benefits of something positive they’d strived for in their day-to-day lives. They also tended to be more resilient to the disappointment of not winning in comparison to counterparts who responded more strongly to losing at a game of chance. According to Luking, "this means that girls whose brains are more responsive to winning are better able to reap the benefits of the positive experiences that they create in their own lives."

The study found that participants with a more robust brain response to losses responded more intensely to negative life events that were out of the locus of their control. They didn’t bounce back from losing as quickly and were more prone to depressive symptoms. “This means that girls whose brains are more responsive to losing are more vulnerable to the effects of negative events, particularly those beyond their control," Luking said.

The authors conclude: "Increasing response to winning or decreasing responses to losing, may be important for both improving resilience and reducing risk in different environmental contexts." Ventral Striatal function appears to be the brain activity linked to the robustness of someone's response to winning and losing.

Other research (Will et al., 2017) found that self-esteem is tied to being "liked" by an anonymous observer rating you positively in a game setting via the ventral striatum. By connecting the dots of these two studies, one could speculate that an upside of loving to win but also being able to let losses roll off your back may be tied to one's ability to avoid having his or her self-esteem tied to whether or not you believe others will like you less if you "lose."

Below are three questions I asked myself after reading about this new research that helped me relate these findings on winning/losing to my daily life that might be helpful for you, too. Using a basic positive psychology scale of -5 to +5 (with zero being a neutral state between happy and sad):

- How elated do you feel after "winning" at something you’ve been practicing and trying to master?

- How dejected do you feel after faltering or "losing" at some type of performance or competition?

- How long after completing the task at hand does having “won” or “lost” impact your mood and self-esteem?

From a coaching perspective, it seems to me that a 2:1 ratio of loving to win vs. hating to lose is a healthy “unity of opposites” sweet spot. Based on life experience, I've found that succeeding at a challenge and “winning” generally gives me a positive feeling of +4 out of a possible +5. Whereas, not performing at the top of my game or “losing” generally gives me a negative feeling of -2 with -5 being the absolute pits.

Most importantly, from years of countless “losses” and a spattering of victories as an athlete, my brain is hardwired to immediately let go of both negative and positive feelings related to self-worth after "winning" or "losing." And, as cliché as it sounds, like everyone, I always learn more from making mistakes and falling flat on my face than performing flawlessly.

Based on a "unity of opposites" philosophy, the key to straddling the paradox of being able to say "I love to win, but don't hate losing," is realizing that winning and losing both have pros and cons but that having a more robust response to winning may help you become more resilient and less depressive.

From a pop music and real-world perspective, Stevie Nicks is a role model for me in terms of her ability to frame "wins" and "losses" in a way that keeps her resilient and has led to an enduring "rock 'n' roll" career since the 1970s. In her 1991 song, "Sometime's It's a Bitch," which Nicks co-wrote with Jon Bon Jovi, she sings: "I've run through rainbows and castles of candy, I cried a river of tears from the pain. I try to dance with what life has to hand me. My partner's been pleasure, my partner's been pain. There are days when I swear I could fly like an eagle and dark desperate hours that nobody sees. My arms stretched triumphant on top of the mountain or my head in my hands, down on my knees. I've reached into darkness and come out with treasure. Sometimes it's a bitch, sometimes it's a breeze. And if I could, I'd do it all over again.”

In closing, please take a few minutes to watch this video for some inspiration that might help you master the art of cherishing wins, while simultaneously being able to let go of losses without beating yourself up:

References

Katherine R. Luking, Brady D. Nelson, Zachary P. Infantolino, Colin L. Sauder, Greg Hajcak. "Ventral Striatal Function Interacts with Positive and Negative Life Events to Predict Concurrent Youth Depressive Symptoms." Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging (First published online: July 30, 2018) DOI: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.07.007

Geert-Jan Will, Robb B Rutledge, Michael Moutoussis, and Raymond J Dolan. “Neural and Computational Processes Underlying Dynamic Changes in Self-Esteem” eLife (First published online: October 24, 2017) DOI: 10.7554/eLife.28098