Resilience

The Power of Personal Problems in Adolescent Life

Problems may be unwanted, but coping with them can strengthen adolescent growth.

Posted January 18, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Three common kinds of adolescent problems are something to solve, something to persevere, and something to suffer.

- A "problem" is a judgment call declaring a discrepancy between how things are and how one would like them to be that causes dissatisfaction.

- Coping with problems can be strengthening when figuring out takes intelligence, when effort takes persistence, or when recovery takes resilience.

Problems can be costly and complicating. They take energy to contend with and make life more demanding: “What must I deal with now?” So, consider problems in three common forms: problems as something to solve, problems as something to persevere, and problems as something to suffer.

Kinds of Problems

- Problems to solve can be confusing: “I don’t know what’s going on or what to do in this situation!” The younger teenager wonders why she wasn’t socially included. Or the older teenager finds functional independence comes with a lot to figure out. These kinds of problems demand to be understood. They prompt the puzzled person to search for a solution or explanation. They arouse curiosity.

- Problems to persevere can take commitment: “I must keep hanging in there!” The young teenager pledges to the slow rehabilitation of a sports injury. Or the older teenager must develop more self-discipline to support growing independence. These kinds of problems can take constant trying. They prompt the beset person to work a difficult or tiresome circumstance through. They create challenge.

- Problems to endure can be painful: “Because of what happened I’m really miserable!” The younger teenager has to deal with loss from his romantic break-up in high school. Or the even older teenager now finds themselves missing the secure comforts of home. These kinds of problems can be unhappy to deal with. They prompt the injured person to feel suffering and sorrow. They require recovery.

And, of course, major problems are often experienced as some mix of these basic three: “Moving and changing schools in seventh grade has upended my life!” Now the young person is figuring out the new middle school, is making every effort to form new relationships, and is sorely missing old friends left behind: “I’ve got problems on top of problems!”

Dealing With Unhappy Problems

To a degree, all unhappy problems are self-made because they are judgment calls about what is or isn’t happening that one decides is not OK. Painful problems are negative comparisons or complaints: “The way things are is not how I want them to be!” This discrepancy can create dissatisfaction that causes unhappiness: “I’m feeling really down about how things turned out!”

In simplest terms, there are only three ways to alleviate unhappiness problems. The person can change how things are to how they want things to be: “I feel better after getting things to go my way.” The person can change how they want things to be to fit how things actually are: “I feel better just adjusting to reality.” The person can do a mix of the two: “I feel better changing what I can and accepting what I can’t.”

Being Problem-Prone

Deciding they have a problem, a young person tells themselves that something needs fixing or changing in their life: “I’m not OK how I am.” At worst: “I'm never going to be like others who I like!” Now they have created a discrepancy between how things are and how they want things to be, thereby breeding dissatisfaction that can motivate corrective action. They may try to change something about themselves or in their world, or they may create an ongoing sense of discontent with themselves if they do not: “What’s the matter with me?” A lot of middle-school adolescents, in the throes of puberty and competition to socially belong, are tormenting themselves with this question, so it's important that parents never ask: "What's wrong with you?"

Confronting a Problem

Young people can sometimes use help choosing their problems wisely: “You may have enough complaints about yourself right now without adding more.” Having said this, it can take courage to declare, confront, and then address a problem. Judging oneself deficient isn’t fun. People tend to be judgmental about how they are and how their life is unfolding: what is going right and wrong, well or badly, succeeding or failing, for example. Declaring a problem can address some deficiency and motivate desire for personal change: “I don’t have any friends!” However, problems don’t just specify something wrong; they can also motivate making something right. “I’m going to be a joiner, not a loner!” So, while problems can inflict pain, they can also motivate progress, sometimes combining a mix of both.

Problems Made by Parents

Parents can add to adolescents' problems. “How can you be OK letting schoolwork go?” asks the baffled parent of the capable young teenager who has given up caring about grades because now "social" feels like it counts more than "academic." One part of parental oversight can be declaring an adolescent problem where the young person wants his life left alone: “Performance now will affect your future opportunities; therefore, we will supervise your homework to see that it gets done.” Conscientious parents are often problem makers this way, sometimes unpopular on this account: “Quit bugging me!” The parents reply, “We are on your side, not against you. Keeping after you is a hard part of our job.”

The Gift of Problems

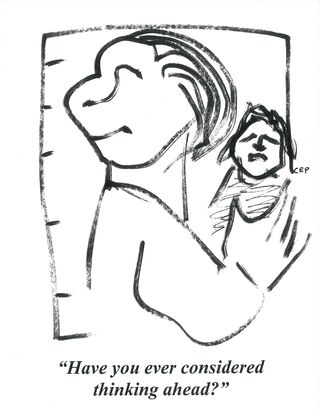

How should you advise your adolescent about problems? Maybe treat all problems as gifts of adversity—the opportunity to claim hard-earned benefits from coping with obstacles in life.

- Figuring out takes intelligence: “Problem-solving is like cracking a puzzle or fixing what’s wrong.”

- Coping with challenges takes persistence: “Determination requires not giving up until achieving what matters.”

- Recovering from hurt takes resilience: “Getting over injury is like growing from feeling badly to finding how to feel better.”

We may not enjoy the problems in our life, but people often gain capacity from coping with difficulties they bring. Thus, if a young person engaged with significant hardships growing up, she or he may have claimed valuable strengths on that account. Increased intelligence, persistence, and resilience can stand them in good stead as normal frustrations and setbacks of young adulthood unfold.

What the young person discovers is this: When treated as tests, problems are often opportunities in disguise, having much of lasting value to teach from hard-earned experience. A kind of seasoned confidence can result: “Tough times I’ve known have prepared me for tough times ahead. I’ve been there before.”