Grief

Children in Grief: Crying Is Brave

How children can process sadness and grief

Posted September 13, 2019

I had a summer screen time blog all written and ready to post on this website. Then our family dog got very sick and eventually passed away earlier this week. In an instant, work, emails, newsletters, and to-do lists flew off the priority list and grief took its place. Jasper, our 13-year-old husky, lived an incredible life and was running river trails until weeks before his passing. But grief is grief. And this dog was certainly a beloved member of our family.

I’m back to work but the priority list remains in flux. I have some mourning to do, yes. But I am also watching another powerful thing unfold – the grief of my 5 and 8-year-old sons. I know that they will have a lot more to mourn than the family dog in their lifetimes, but how they are navigating this loss has a lot to teach us about grief both big and small. So rather than force a screen time post my dad and I decided to share a few insights with you from kids. We have a lot to learn from them.

THREE INSIGHTS FROM AN EIGHT-YEAR-OLD:

1. Let me cry. Crying is brave.

For a long time children (especially boys) have been told to be brave and not cry. Research shows that though all genders are equally as emotive as babies, boys especially tend to “get the vulnerability socialized out of them.” Yet learning how to experience, name, and manage emotions is one of the central tasks of childhood and leads to all kinds of good outcomes later in life. Social norms like “big boys don’t cry” eventually hurt all of us.

So let your kids have a good cry. Or five. As an educator mentor of mine, Julia Dinsmore, often tells her students, “Don’t apologize for crying. Crying is holy water.” Your kids have a lot to learn from their tears.

2. Remind me that I can feel two (or three or more) feelings at once.

Children sometimes think they only have room for one emotion at a time. For example, this week my older son noted, “I am looking forward to playing my new game, but I can’t be excited.” Remind your child that it is okay to be sad about loss and excited or joyful about something else. Or to be both sad and mad. Normalize and talk about having multiple feelings at once. Grieving is a mess. Let it be.

3. Let me take breaks.

Handling big feelings of stress or sadness can be overwhelming. It isn’t uncommon to see kids sobbing one minute and then seeking out a toy to play with delightedly shortly after. Let kids move in and out of intense feelings even if you can’t yet. Engaging in grief in short bursts can help children handle it.

THREE INSIGHTS FROM A FIVE-YEAR-OLD:

1. Just because I am not crying doesn't mean I am not upset.

When we told my youngest son that our dog was dying, he did not respond with meaningful eye contact and tears of sadness. Instead, he started rolling around on the couch and immediately asked if he could watch a show. Five minutes later he hit his brother.

Often, sadness comes out “sideways” in kids (and teens). In other words, they may not appear to engage, but instead become more irritable, defiant, clingy, or avoidant. Be patient, gentle, and provide extra hugs and reassurance as they work out their feelings.

2. Speak to me gently and clearly.

It can be tempting to avoid talking to younger children about death or speak in coded language instead. For example, “He went to sleep forever” might feel less harsh than saying, “He died.” But coded language can be really confusing for kids trying to figure out what is happening. Use gentle, but direct and clear language with small children.

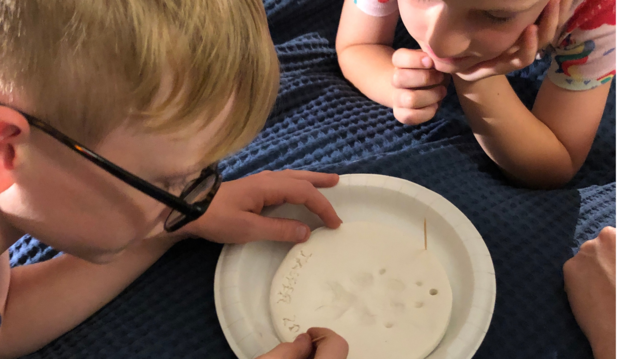

3. Invite me to do something.

While my youngest son’s very first response to the news might have seemed disengaged, the care that he took decorating our dog’s memorial indicated otherwise. Some kids may not have a lot of words to express how they are feeling, but funneling their energy into creating art, writing a note, or participating in a ritual can be very soothing. Here are some ideas of arts and crafts activities around grief.

What is amazing about kids is that as we pay attention to and respond to what they need, we learn a lot about what adults need too.

References

Weinberg, M. K., Tronick, E. Z., Cohn, J. F., & Olson, K. L. (1999). Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 175-188.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2004). Children’s Emotional Development Is Built into the Architecture of Their Brains: Working Paper No. 2. http://www.developingchild.net

Schonfeld, D. & Quackenbush, M. (2009). After a Loved One Dies—How Children Grieve And how parents and other adults can support them. New York Life Foundation. New York: NY.