Anxiety

Weapons of Mass Distraction

Why we have lost the ability to focus

Posted December 18, 2012 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Last Sunday, I read a New York Times article entitled, “Learning to Let Go: First, Turn Off the Phone.” As someone who studies the impact of technology, particularly the impact on our own personal psychology, I was interested to see what Andy Isaacson, the article’s author, had to say about what our omnipresent phones are doing to us.

I have to say that I was both encouraged and discouraged. On the plus side, the article tackled what I think is a major issue in our smartphone-inundated world: the fact that in the past five years, we have all started to carry around in our pocket or purse a wireless mobile device that purports to be a phone, but, in fact, is really more of a computer. What used to be a charming and somewhat amusing acronym—WMDs, standing for wireless mobile devices and not weapons of mass destruction—has now morphed into a totally different type of WMD that I call Weapons of Mass Distraction.

According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project’s recent November 30, 2012, report, 67 percent of cell phone owners find themselves checking their phone for messages, alerts, or calls even when they don’t notice their phone ringing or vibrating. Nearly half sleep with their phone next to their bed because they want to “make sure they didn't miss any calls, text messages, or other updates during the night.” You might think from these staggering statistics that Pew studied a sample of teenagers or young adults. In fact, they surveyed 1,954 American adult cellphone owners spread rather evenly among young adults (18-29), young-to-middle-aged adults (30-49), older adults (50-64), and senior citizens (65 and older).

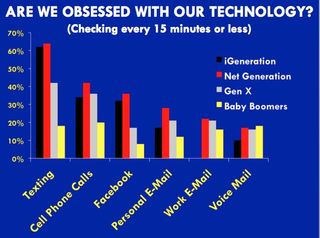

In my own research, I have seen a similar trend, including data seen in the following charts. The first chart breaks down a large sample of members of four generations, roughly paralleling the Pew data with the iGeneration born in the 1990s, the Net Generation born in the 1980s, Generation X born between 1965 and 1979, and the Baby Boomer Generation born between 1946 and 1964. In this particular study, we looked at how often people of different generations checked various technological communication tools.

As is obvious, younger generations are more obsessed with their text messages and less so with their phone calls and Facebook (although still roughly 4 in 10 checks every 15 minutes or less). Gen Xers are somewhat less obsessed, and Baby Boomers are less likely to be constantly checking their phones at all.

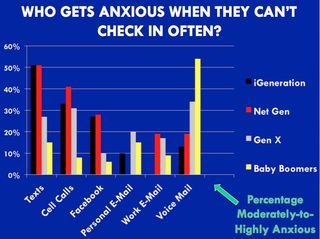

The second chart (below) is from the same study, where we asked, “How anxious do you get if you can’t check in with each technology as often as you like?”

As you can see, half of the two youngest generations get moderately-to-highly anxious if they can’t check their texts, and slightly fewer get anxious if they can’t check cell calls or Facebook. Far fewer Gen Xers get this anxious, and it appears that Baby Boomers only get anxious if they can’t check their voicemail (perhaps from their work or their family).

As even more corroboration of these obsessive tendencies, Dr. Michael Rothberg and his colleagues at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Massachusetts, and Dr. Michelle Drouin and her colleagues at Indiana University-Purdue University in Fort Wayne, studied “phantom vibration syndrome” or perceived vibrations from a device that is not really vibrating.

Both found that nearly all of their sampled subjects experienced these odd vibrations and did so at least once every two weeks on average, with many experiencing it daily. You will have to be the judge of your own experiences with this modern-day affliction, but I can tell you that I feel my own pocket often vibrating without it being the phone and notice that others do the same. When I am out with friends, invariably someone will pull their phone out of their pocket or purse, look at it quizzically, and put it right back (unless, of course, the draw to peek at Facebook or Twitter or any other social media website is just too strong).

Before smartphones, if we felt a random tingling sensation in our upper leg, say just under our pocket, we would have reached down and scratched an apparent itch. Now we have totally changed how we perceive this neurological stimulus, and our anxiety has convinced us that it must be a signal that someone is trying to communicate with us, and we need to check who it is and what they want… and we must do it immediately. MTV called it FOMO—fear of missing out—but I call it an obsessive behavior.

The media often asks me about whether we have become “addicted” to our devices, and for the most part, with the obvious exception of gaming devices, I believe that we are not addicted at all, but rather we are obsessed.

Biochemically, these two psychological responses emerge from two different brain chemistry states. Although this is simplifying a complex biochemical reaction, addiction stems from a need to increase neurotransmitters such as dopamine and endorphins (among others) in our brain, while obsession stems from a need to decrease neurotransmitters that are related to anxiety (although obsessions also increase other neurotransmitters that block positive, elevated moods and produce anxiety). It is rather complex, and I am not a neuroscientist, so I am not completely immersed in the impact of media on neurotransmitters.

However, I do know that what we are seeing is akin to watching Jack Nicholson battle his OCD and continue to lock and unlock his door and wash and rewash his hands in the movie As Good As it Gets. Jack’s character Melvin was trying to decrease the anxiety he felt about leaving his door unlocked and being afflicted by invisible germs. Sadly, I don’t see this as all that different from those people who check their phones constantly, even when they have not been alerted to incoming communication.

Getting back to Isaacson’s article, he tells us about a lounge in San Francisco that has a sign that states, “You are now entering a technology and device-free zone. Please refrain from using your cellphone inside this space. The use of WMDs (wireless mobile devices) is not permitted.”

He talks about how the lounge had launched a Device-Free Drinks party to “enjoy a few hours off the grid” and how different people reacted. What saddened me is that those patrons that Isaacson quoted mostly talked about how difficult it was to let go of their devices, and one had to sneak back to the “device check room” to call someone and noted with awe that she had lasted an hour. Others dabbled in hand-drawn art but planned to upload it to Instagram as soon as they left the lounge.

The evening was arranged by a recovering techie who runs Digital Detox programs, which are four-day weekend retreats where people give up all technology and learn a variety of skills, designed to help relax and reduce anxiety. I first wrote about attempts to live for periods of time without devices more than two years ago in a Psychology Today blog post entitled, “Taking a (Virtual) Break: Can You Survive Without Your Technology for 24 Hours? I Doubt it!” In this blog post, I described two failed experiments to eliminate technology for a short time and the reactions of the people who tried.

One of the participants summed up his reaction to the experiment by saying, "I feel really anxious because I don't know if I'm missing something important. I keep thinking I can't wait for this to end, because I need to check my e-mail. How many Facebook notifications am I going to have after this?"

The article also saddened me because it pointed out something that I have noted as I have studied the evolution of our psychological reactions to technology for the past 30+ years. For some reason, we have become convinced that the only way to fight the anxiety that drives our smartphone obsession (feel free to substitute any other technology activity here for your personal obsession) is to give it up for large chunks of time. I am not convinced that that is even a reasonable strategy, and I am more convinced than ever that it will not work.

The crux of the issue is that we have lost our ability to attend and focus. Sure, we can focus if we really try, but when you read a book or magazine, don't you feel your mind wandering after just a few short minutes? I used to enjoy reading long New Yorker articles and now find myself impatiently thumbing ahead to decide if I can read to the end before switching to doing something else.

The Week magazine, along with most other magazines and television news reports, distills our world into short bytes so that we are not held captive for too long. Research out of my lab and others show that students, computer programmers, and even medical students are able to focus for only three to five minutes before being distracted. Guess what the biggest distraction is: Technology! In my study, it was smartphones and Facebook, while others have found e-mail to be highly distracting in the work environment. In a study of the role of technology in getting a good night’s sleep, members of my research lab found that smartphone use in the last hour before bed and smartphone interrupted sleep were the major culprits.

We are, I believe, at a critical juncture, perhaps as important as a paradigm shift, in how we relate to the people we communicate with through our mobile technologies at the expense of those human beings who are physically present in our world. I cringe a bit when I see young adults at a restaurant and watch them pick up their phones (positioned next to their dinner plate), tap a few keys, and try to resume a conversation.

I understand that young adults have a new game where everyone puts their phone on silent and stacks them all in the middle of the table. The first to succumb and grab a phone has to pay the whole bill. After watching people surreptitiously check their phone in the middle of a movie and even during an airplane flight (yes, I have seen people do this against all FAA warnings), I don’t think that this game will do anything but increase the omnipresent anxiety.

So, what is the solution to this problem? I believe that it is time to retrain ourselves that we are not going to die or be left out of something vitally important if we are not checking our smartphones all day and night long. In my book, iDisorder: Understanding Our Obsession With Technology and Overcoming its Hold on Us, I provide myriad strategies for taking small breaks from technology, including going outside and looking at nature, exercising, listening to music (not while multitasking!), talking to someone on the phone, and looking at art.

My recommendation is that you eventually train yourself to take one of these breaks every hour or so. First, start with a 10-minute break every two hours of inundation from technology and then decrease the time between breaks, slowly from two hours to an hour and, if you can do it, increase the break time itself from 10 minutes to 15 minutes or—gasp—even longer. This will train your brain to slowly eliminate the neurotransmitters that signal that you are anxious and allow you to work more effectively during the time that you are using technology.

If your brain is filled with worry about what you might be missing out on, it is doubly difficult to focus your attention on a task at hand. This will also help you increase the time you focus on a single task since you are removing the constant interruptions from technology. Do note that at the beginning, when you are working between nontechnology breaks, you might need to close your e-mail and turn your smartphone on silent to avoid interruptions.

If you are using an hour as your focus time, this will likely make you nervous, so try giving yourself permission to check in with your silenced phone, say, once every 15 minutes for a minute or two, and then silencing it again. Over time, you will find that you don’t need to check-in so often, and perhaps once in the middle of the focus, time will be all that you need.

The bottom line is that we have lost our ability to focus and attend to our work and our immediate social network (our real, face-to-face social network, not our virtual ones). We need to retrain our brains to discover that we don’t need to be anxious and check in with our technology all day and night long. We just need some brain training.