Leadership

Is Your Leadership Strategy Sustainable?

Why we are asking too much from our leaders.

Posted June 23, 2020

The role of a leader has drastically changed in the last few decades. Previously, leaders played more of a literal management role. They managed resource allocation, budgets, technologies, coordination of people, etc. As the expression goes, they worked on finding the right people, at the right time, in the right place, with the right tools.

Now we expect managers to be more like senior leaders—that is, be strategic, align people to the vision, coach them for self-improvement, etc. When we look at the former definition of a manager we see those responsibilities now sit with those who have a supervisor or project manager title. And those with the manager title are more aligned to the latter definition, acting as mini-executives for their teams. Middle managers are facing the brunt of this transition by trying to play both roles at once. That is, they are expected to both translate the strategy and manage the details.

This transition from manager to leader is creating unsustainable expectations. A fact that is particularly apparent now that we see 26-40% of people are extremely stressed or burned out at work1.

Why is the leader role unsustainable?

First, let’s crunch some numbers. Let's first assume that we have good intentions and don't want our managers to work more than an eight-hour workday. In a year, that gives us 2,080 hours to work with.

Oh wait, we need to remember there are 12 public holidays (in Canada) and a basic entitlement of vacation of two weeks (though it's more likely to be three or four weeks). And although we don't want managers working more than eight hours a day, let's be a bit tough and only allow the legally mandated 30 minutes a day for lunch, bathroom, and coffee breaks. So at most, managers have 1,785 hours in a year.

Okay, now we assume each manager has the median number of employees reporting to them, which is seven2.

Now, let's consider the elements of what a manager does:

- Business strategy activities (planning, forecasting, aligning, etc.)

- People management and development activities (performance management, succession planning, coaching, recruitment, onboarding, safety, etc.).

- Self-development (mentorship, training, learning, etc.)

- Stakeholder management (customer interactions, union, cross-functional collaboration - marketing, R&D, etc.)

- General administration (budgeting, expenses, calendar scheduling, etc.)

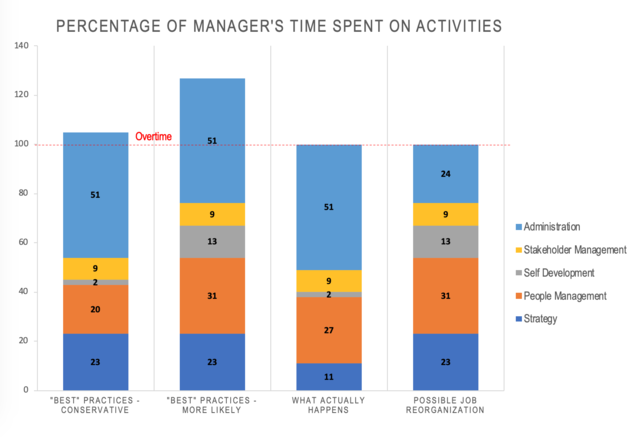

Considering these buckets, how many hours should be dedicated to what? Depending on your company values and strategy, the percentage you dedicate to each will vary. Or it should. Unfortunately, many organizations don't seem to actually give and take one aspect of the role for the other, they just expect managers to do it all within a finite amount of time. Let's break down 'best practices' or estimates of how much time each of these take in a manager's role.

Business strategy activities are the most important activities and usually the aspect that never gets done3. Why? Because it takes brainpower, it takes long-term thinking, and it doesn't provide immediate reward or incentive. To help focus on strategy, some4 suggest about one day a week should be devoted to strategic planning, monitoring, and realignment. So that's 416 hours or 23% of a manager's time.

For ongoing performance management, it's recommended that managers meet with their employees once a week for an hour5. This is generally to check in on objectives, discuss learning & development opportunities, resolve conflicts, etc.. This results in 364 hours (or 20% of a managers' time) in a year. Keep in mind, I'm not even considering the amount of prep time or debrief time that may be needed for these meetings.

If you are farther along in your talent management journey you may have managers do their own succession planning and sit in on talent reviews. On average, we see managers spend 113 hours (or 6% of managers' time) on this formally, which includes writing development plans, attending meetings, etc. and does not include informal discussions or thinking time (which typically adds another 70 hours on - which would bring it up to 10% of their time)4.

At a bare minimum, all employees are recommended to work on self-development or training for 40 hours a year6. However, depending on the person, the role, and the organization's offerings, additional training may be needed or desired. For example, mentoring programs take a minimum of two to three hours a month7. Accelerated leadership development programs typically require four to five hours a week for six to eight months8. So depending on the requirements, self-development requires between 40-236 hours a year, or 2%-13% of a manager's time.

Now, what about stakeholder management? Not every manager needs to interact with other groups such as marketing, research & development, supply chain, unions, shareholders, the external community, or even customers. But generally, all leaders will need to work with shared services (e.g., human resources, finance) and operations in some way. This could be for general status quo collaboration or it could be in pursuit of achieving strategic objectives or special projects. Approximately three hours a week are required to manage internal stakeholders4, so a conservative estimate is 156 or 9% of a manager's time.

I'm willing to bet that everyone would agree that administrative tasks should be the lowest percentage of a manager's day. Unfortunately, it is the largest. On average, employees receive at least 150-200 e-mail messages a day and spend about two and a half hours reading and replying to them9. And remember emails are still sent even if you are on vacation, so that's 650 hours a year. Annual and monthly budgeting and forecasting take on average 32 days10, which is 256 hours. And depending on whether you have an assistant or not, scheduling and expenses can add even more hours to your day. Let's conservatively say that general administration takes up 906 hours or 51% of a manager's time.

So if you have been keeping track, we are now at, conservatively, 1,882-2,261 hours, which is 97-476 more hours than managers have time to do. It's a conservative estimate because I'm not even taking into consideration any employee turnover (and subsequent recruitment and onboarding time), calendar scheduling, safety talks, rework time, or sick time. This crunch of hours typically this means managers sacrifice long-term strategy for short-term firefighting, which doesn't help the organization meet its goals. Alternatively, managers end up working those conservative two to nine extra hours a week and sacrifice their home life and/or their health. This will increase their odds that their performance will suffer, they will need to go on leave, and/or they will quit.

So how do we make the leader role sustainable?

As you can see from the chart below, the way we can help ease the demands on a manager, as well as make the job more engaging, is to reduce administrative tasks. Administrative tasks should be limited to those clearly linked to business strategy or development, like budgeting and forecasting. However, there are other tips that can help the leader role below:

- Automate as much as administrative tasks as possible (e.g., expenses logged through cell phone photos)

- Set email guidelines (e.g., who should be cc'ed when and why, e-mails only to document actions or decisions required)

- Determine what percentage of manager's time should be devoted to what based on your strategy. For example, if some managers have key relationships with major clients, have them devote more time to them and perhaps reduce how may direct reports they have or increase their administrative staff to reduce that workload.

- Streamline and integrate all your people management processes so that they are simple and add value.

- If you put leaders in accelerated development programs, be explicit about what work they can take off their plate or provide additional resources for them to help distribute the work. Alternatively, some programs require leaders to have developed their team well enough that the role will have coverage while the leader is developing themselves.

- Consider alternative work designs

I would love to hear what other tips you have. Comment below!

References

1) in North American samples: The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, n.d; Centre for Disease Control, n.d.

2) Conference Board of Canada, 2015

3) Martin & Horwath; Strategic Thinking Institute

4) Corporate Executive Board, 2013

5) Gallup

6) Corporate Executive Board, 2005

7) Alred, Garvey, & Smith, 1998

8) Bersin, 2011

9) Harvard Business Review, 2019; Forbes, 2017; McKinsey, n.d.

10) CFO, 2017