Chronic Pain

Chronic Pain and Pain Assessment

On a scale of one to ten.

Posted January 29, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

I have been in pain every day since I was 20 years old because of what I now know to be a genetic disorder of my connective tissue. As a result, I’ve been asked approximately one zillion times by healthcare providers of all kinds to rate my pain on a scale of 1 to 10. Sometimes they have progressively unhappy faces to accompany the numbers, but usually, they just offer up that 1 to 10 scale, and I’m supposed to make sense of it on my own.

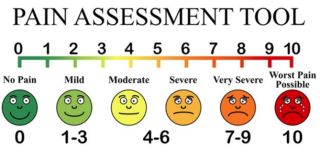

The no-pain face at zero has a big easy grin, a basic happy face with the addition of eyebrows that get ever-scrunchier as we move up the scale. The color heats from a cool forest green to blood red as the pain worsens, and by the time we see our “worst pain possible” face at a 10 there are tears running down it, big dark circles clouding its vision, and the eyebrows are the total inverse of the now huge frown.

The faces are adorable, but seriously, what are the units? How do I answer when I can’t remember what zero feels like? How do I separate the stabbing neck pain causing a massive headache from the soul-sucking ache in my low back? And really, why does it matter? How will this ridiculously subjective information be used?

As a decades-long chronic pain sufferer, I promise I would not drag myself out of the house to talk to some pimply-faced resident unless the pain was pretty freaking bad. And I can tolerate an awful lot of pain. I almost always offer a number that is lower than feels true because if it’s a nice doctor I won’t want them to feel bad for me, and if I don’t like them I’ll be afraid they won’t believe me if the number is too high.

I never start below a 3 because the pain is always there and always uncomfortable enough to call my attention. And on the opposite end, I almost never put my number above 8 because I decided giving birth felt like a 9, and anything above that must mean I’m pretty close to dead. Anywhere in between is pretty much a stab in the dark.

The whole problem is that the experience of pain is utterly personal. When my son sprained his ankle at soccer and it hurt so bad he couldn’t walk, he called that a 10. And who am I to argue?

The pain scale comes up a lot for me because I am on a regimen of opioid pain pills that I have taken for seven years to manage my condition. [Side Note: I do not care if you read the research that says taking those meds doesn’t actually help or makes the pain worse. You are wrong. Those drugs make me functional and I’ve tried so many other approaches from crystals to invasive surgeries that if I named them your eyes would glaze over.]

Anyway, to acquire said pain pills I have to go, in person, to my pain doctor every 28 days and answer that stupid 1-to-10-question and pee in a cup for a drug test. I’m not trying to be precious here, I absolutely should be checked up on and I, myself, worry about becoming addicted. It’s just that monthly feels super excessive, especially for someone who has been successful on the same meds for so long, and extra especially since the precise pain I need treatment for is made worse by getting in a car to drive across town and sitting in a waiting room.

That meaningless, subjective 1 to 10 question is a special kind of torture in that context because at any moment some bureaucrat from the government or the insurance company might decide that only people who give the “right” answer on the pain scale get access to the drugs, and if I get the answer wrong then I lose access to the drugs that make my life possible.

Recently, I was asked to research validated pain scales for a public health study I’m working on. It turns out the 1 to 10 question with the faces is validated, for pediatric cancer patients. So are a bunch of different other ways to ask about pain that has been tested in other populations with other kinds of pain.

And then I came across the Mankoski Pain Scale (see below), which was developed by a chronic pain sufferer. It’s a 1 to 10 scale, but she went to the trouble of describing each of the levels and what they mean for people like me, who experience pain every day and have for years.

I can’t stop laughing about this new one, not because it’s funny, but because it’s so ridiculously helpful. Out the window goes my own, personal, arbitrary and mood-based scale. Instead, I can use this scale to give anyone a meaningful and consistent assessment of my pain. It turns out, I live my day-to-day life between a 5 and a 6. A long car ride bumps me up to 7, and airplanes take me to an 8. Labor was definitely a 9, so at least I was right about that.

Just like getting my diagnosis after years of searching, this pain scale makes me happy and sad. Happy because it’s hugely validating to see something that is so much a part of my daily experience become named and concrete. Sad because seeing it in writing this way makes it feel real and big and like an awful thing to have to endure for the rest of my life.

Nevertheless, living with a nebulous, chronic, and limiting illness is utterly isolating on many different levels. It’s relentless, difficult to explain, and depressing; and even though it’s only a small part of who I am, it dictates far too much of my life. That makes it incredibly powerful when someone gives structure and meaning to any part of it, as Mankoski did to this tiny question with a big impact.

(I’m printing it up poster size for my pain doc to hang on her wall.)

Rate your pain on a scale of 1-10:

● 0 – Pain-free

● 1 – Very minor annoyance – occasional minor twinges. No medication needed.

● 2 – Minor annoyance – occasional strong twinges. No medication needed.

● 3 – Annoying enough to be distracting. Mild painkillers are effective (aspirin, ibuprofen).

● 4 – Can be ignored if you are really involved in your work, but still distracting. Mild painkillers relieve pain for 3 to 4 hours.

● 5 – Can't be ignored for more than 30 minutes. Mild painkillers reduce pain for 3 to 4 hours.

● 6 – Can't be ignored for any length of time, but you can still go to work and participate in social activities. Stronger painkillers (codeine, acetaminophen-hydrocodone) reduce pain for 3 to 4 hours.

● 7 – Makes it difficult to concentrate, and interferes with sleep. You can still function with effort. Stronger painkillers are only partially effective. The strongest painkillers relieve pain (an extended-release form of oxycodone, morphine).

● 8 – Physical activity is severely limited. You can read and converse with effort. Nausea and dizziness set in as factors of pain. The strongest painkillers reduce pain for 3 to 4 hours.

● 9 – Unable to speak. Crying out or moaning uncontrollably, near delirium. The strongest painkillers are only partially effective.

● 10 – Unconscious. Pain makes you pass out. The strongest painkillers are only partially effective.