Friends

The Giftcurse of Original Suffering

"Fortunate is he who understands the cause of things." (Virgil)

Posted October 27, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

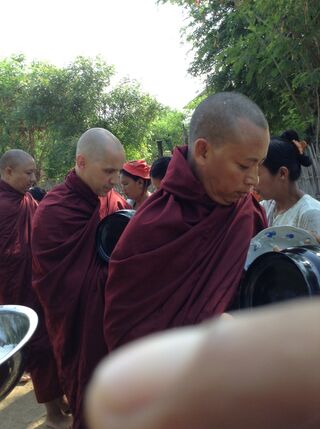

In one life, I am someone who ends up going to Myanmar to be a Buddhist monk. At my ordination, after accepting my vows, the abbot of the monastery gives me a new name. I become at that moment U Sâsana.

As tradition has it, in Theravada Buddhism as practiced in Burma, one’s name is meant to be a kind of counsel for you, a path forward for you, a way to define and inform your character. It’s chosen with great, sometimes subtle, sometimes puckish care, your name becoming not only what you’re called in the world, but also who you are, how you are to conduct yourself, and where in essence you need to go. To be named U Sâsana, for instance, is meant to imply that your work in this life is to be a “great sharer” or “great teacher.”

More often than not, one’s life’s work is the most challenging and most necessary way forward. My friend, Myint Tun, is christened U Maheinda, meaning he must labor to be a “great controller of mind,” and Ashin Kelasa explains how his own name is a reminder to settle himself, to strive to become clear, Kelasa meaning “clear water,” suggesting a clearing of murk.

Back home in my other, noisy, busy life—wife, kids, job, bills, internet, friends—I will talk about these experiences in Burma from time to time, bringing them out like souvenirs. I’ll be in class, thinking aloud about character or plot with my students, and suddenly I’ll hear myself remembering certain Buddhist ideas of self and character, the idea of one’s name as an ideal, a kind of star to which one attaches his or her journey, how a name becomes a way to guide one’s choices, a complement and answer to one’s needs as a person.

The Buddhists have this idea of original suffering. This is something you carry with you your whole life. It’s not always obvious to you what the suffering is—or sometimes it’s so obvious that, like oxygen or gravity, you are barely able to notice its existence, let alone count it as anything important—but every step you take can be traced back to this one thing, your giftcurse, your entire character stemming from this.

Now, part of the real pleasures of teaching writing is the feeling that everything one thinks about, everything one studies, everything one encounters in life can be applied to writing. Talking about writing almost always means talking about one’s experience of life. No matter how oblique, everything applies, everything is available for use. “Be one,” as Henry Janes said, “upon whom nothing is lost.”

More than once I will go to become a monk. It will be as far from home as I can get. The antipode, the complete opposite side of the world in every way. When asked why, I’ll explain to friends how I must have been here as a Burman in a previous life. A Burman, or a Brit, someone with a great affinity for his station here, someone who found he loved the heat and rain, someone who could go as if by memory along certain roads and rivers. This will make about as much sense as anything to my Burmese friends. For them it is enough to say you feel drawn to a place. No need to spell out such yearning.

In Myanmar, if you pass unsatisfied from this life, you are reborn on the plane of hungry ghosts, your soul coming back again to complete some piece of unfinished business. As they say, it took the Buddha many lives to become the Buddha. With this in mind, it is possible to have empathy for someone going back and forth over a particular piece of ground, as if trying to find something they have lost, as if trying to lift some curse they have been under.

One afternoon, driving in our jeep from Mandalay to Yangon, we stop at a roadside gas station. There’s a small village nearby, and off to the side a very old woman is selling teak chocks. They’re used as parking brakes for cars and trucks, these fresh-cut wedges stacked in all sizes around her. She’s no bigger than a small boy, this woman inviting us to sit with her in the shade. She offers tea and mangoes. The air is pleasant off the small pond behind the house.

She wants to know the story of us: our heads shaved clean, we explain that we’ve just left the monastery in the forest, just been disrobed, on our way back now to the jungle of the real world. She’s pleased and tells how she’s lived here her entire life.

We’re only there for ten minutes—the space of a cup of tea, the engine of our Jeep ticking itself cool nearby— and she relights her cheroot and tells of her children, her grandchildren, her husband’s death, and how she laughed at her younger brother when she was six years old. She didn’t know any better, the boy in his coffin in the front room of the house, but almost ninety years after the fact she’s still known in the village as the girl who couldn’t stop giggling at her brother’s funeral. It’s in her voice, the acceptance, the odd, enduring sense of identity.

Of all the stories she could have told, that was the one she chose. That must mean something. Of all the things that survived, all the things she might have wanted us to know, it was that single moment from a lifetime, this young girl reacting to the sight of her brother lying there as if asleep.

Later, riding in the jeep, air flapping like a flag at the windows, we’ll each try to name our own original suffering, as if asking for the way forward.