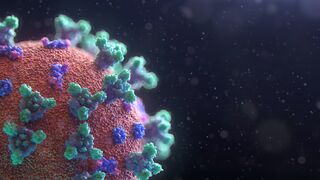

Coronavirus Disease 2019

When Culture Promotes Mobility Does It Also Promote Disease?

The freedom to move between social networks may speed transmission of COVID-19.

Posted June 16, 2020

In 1993, I left the suburbs to start university in downtown Toronto. Four years later, I moved further afield: to Vancouver, to study clinical psychology at the University of British Columbia. During the final year of my doctorate, I moved to New York City to complete a clinical internship at Montefiore Medical Center. And finally, in January 2005, I started working at Concordia University in Montreal.

The above is a quick, convenient way to introduce myself. It also allows me to introduce geographical mobility. What are the effects of repeated moves? With each new city, I underwent a long process of saying goodbye, wrapping up my life, moving, and then slowly establishing a new social network. As a result, I don't have a single social network although I do have friends from different places.

From geographical mobility to relational mobility

Societies vary widely in their support for mobility. My choices might seem outlandish to generations of my Scottish ancestors who rarely left Glasgow. Yet, they would not be unusual to many middle-class Americans. My colleagues in the U.S. often encourage their children to travel much further for their degrees and their jobs than I did back in the day. Of course, there are consequences to frequent moves, just as there are consequences to staying put.

Cultural psychologists have observed that societies with a lot of geographical mobility are also societies that support relational mobility. Certain aptitudes are favored in societies where people are expected to maintain the same network. Other aptitudes are favored when it is important to enter new networks.

Where relational mobility is low, people tend to have a single interconnected social network of family, friends, and acquaintances. Your relationships are lifelong—whether you like it or not. Paying close attention to social harmony makes it easier for you to get by. While you get a lot of support from your social network, much support is expected from you as well. People have your back, but they’re also in your business.

Where relational mobility is high, people tend to move between different networks. You may well have some lifelong relationships but these are freely chosen exceptions. Many more connections are at least somewhat transactional. You need to be willing to promote yourself, and a little extraversion goes a long way. If your friends don’t make you happy, you need to find better friends.

Relational mobility around the world

The reasons for — and consequences of — this distinction can help us understand how individual psychology and cultural context influence one another. An ambitious cross-cultural project was recently conducted by Robert Thompson of Hokkusei Gakuin University in Japan, together with colleagues around the world. They studied relational mobility in 16,939 people in 39 societies. Not only did they document cultural differences, but they also explored the reasons for such differences. The search for reasons, which cultural psychologists call unpacking culture, is not done nearly often enough.

They found that relational mobility is highest in Europe and the Americas and much lower elsewhere, and especially low in Japan. The United States and Canada turn out to be similar — well above the global mean but not as mobile as Mexico. Not only can you read their open-access paper, but the authors also provide an online visualizer allowing you to play with these data to your heart’s content.

I will highlight two important findings:

- Societies that report more relational mobility tend to be those with a history of (a) herding-based agriculture and (b) migration from many parts of the world. These findings make sense: Herding and migration both require mobility.

- Another set of reasons comes from the local environment. Societies where there has been more ecological threat report less relational mobility. Examples of threat include harsher climate and risk of infectious disease. It pays to be careful about moving between social circles if the risk of exposure to dangerous pathogens is high.

Culture, relational mobility, and COVID-19

Had I started this blog a year ago, I would shift here to interesting research about how relational mobility predicts specific forms of social anxiety. Perhaps I’ll get back to that at some point—but this year, dangerous pathogens are on everyone’s minds. Might cultural psychology be relevant to pandemics?

Some colleagues and I just finished a factsheet summarizing work on this topic for the Canadian Psychological Association. A lot of this research is, unsurprisingly, based on previous pandemics such as SARS or H1N1. But some researchers are moving quickly—a recent paper has used archival data to study the influence of relational mobility on the spread of COVID-19.

The project was led by Cristina Salvador, a graduate student at the University of Michigan working with Shinobu Kitayama, one of the founders of contemporary cultural psychology along with several other collaborators. They started with the 39 societies studied by Thompson and colleagues. For each society, they then looked at the rate of COVID-19 spread in the 30 days after the first day with (a) at least 20 recorded cases and (b) at least 1 death.

Sure enough, higher levels of relational mobility were related to a faster spread of COVID-19. Other commonly studied cultural differences, such as individualistic vs. collectivistic values or tightness vs. looseness of norms, did not show any effect. Population density and median age made no difference, although more populous countries overall did show faster spread. All in all, we are seeing culture’s consequences in real time.

Conclusions

There are caveats of course. The paper is a preprint and awaits peer review. Also, the pandemic landscape is shifting rapidly and new data might overturn these findings. If they do, I will provide updates. Caution is important, but pandemics create a need to get findings out quickly. We could end up learning important details about how culture influences the spread of COVID-19.

Mobility comes with costs and we do well to be aware of them. But when I reflect back on my own moves, I also see the benefits. For me, each move was an essential part of my education as a cultural-clinical psychologist. I grew increasingly convinced that the cultural perspective on health is not a rival to psychological or biological views. Nature vs. nurture is a stale debate.

Rather, the cultural lens needs to be integrated into the whole. From that perspective, it makes sense that a biological threat might give rise to cultural practices with psychological consequences. And in turn, these practices might influence the spread of a new biological threat. Cultural-clinical psychology places these kinds of patterns at the very center of understanding physical and mental health. I look forward to sharing more examples in future posts.

References