Dreaming

Here's How Talent Actually Works

Talent is all about your ceiling. And that's why generalists do best in life.

Posted June 3, 2019

Carl (not his real name) wanted to be an engineer when he was growing up in Jamaica. He decided the best way to do it was to study physics. The problem was, his high school in the South Bronx didn’t offer physics.

Carl got into Williams College, where I met him. But when he arrived, he’d never taken a physics course. But this kid thrives on challenge, he has a great attitude, and he works very, very hard. He knew he was an underdog, but he decided to major in physics anyway. His plan was simple: If things aren’t going well, I'll just work harder. His motto was: If I refuse to fail, I'll succeed.

It didn’t work out that way. He passed his courses, but he was miserable because he was constantly struggling to catch up. He couldn’t outwork the other students for two reasons. First, he had to earn money to support his mom back home, and he was a varsity athlete, so there weren’t enough hours in the day. Literally.

Second, he thought he could get by on pluck and determination. But when everyone has pluck and determination, that doesn't work. It's not an advantage. Everyone in his physics classes was putting in long, hard hours of work. He couldn’t outwork them.

Carl prides himself on never giving up. He didn’t want to let physics “defeat” him. He felt like he always reached the top of every mountain he'd climbed, because he persevered. He wasn't going to give up on this one.

But quitting physics was not a defeat. He wasn't giving up on climbing mountains, he was just switching to a mountain that was easier for him to climb. A mountain that fit his skills and talents. There’s no shame in that. It's not giving up on a challenge, it's moving to a different challenge and focusing on the things you’re good at. This is a lesson for anyone who's stuck doing something they're not suited for--there's no shame in switching. That's just smart. Carl is smart. When it became clear that physics wasn’t right for him, he switched majors.

In general, it doesn't usually work to choose what you want to do and then try it to see if you're good at it. That's backwards. You should try a lot of things and see what you're good at it, and choose to do that.

Another way of saying this is, Carl had a low ceiling in physics. When he realized it, he switched to something where his ceiling was higher.

The ceiling theory of talent

Everyone has a ceiling. The great ones, they have high ceilings. Take Usain Bolt, the fastest man in history. He took world records that had been set by insanely talented, hard-working people, and he destroyed them. He is a god, which is another way to say he has a very high ceiling for speed.

Then take me. I’m slow. When we used to do sprints in high school, I’d get to that point where you just can’t move faster, and other guys on the team would practically jog past me. I have a low ceiling.

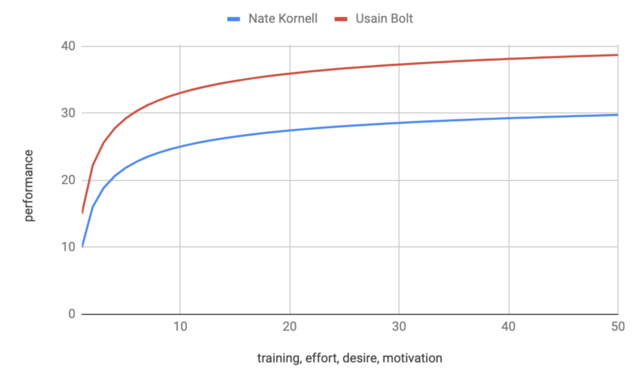

The ceiling theory of talent looks like this (see below). When you suck at something, you’re at the far left side of the curve. The slope of the curve is steep at first because when you’re starting out in something, you can improve a lot by practicing. That’s when you have major problems to fix, and fixing them makes you improve a lot. Later, when you’ve moved further to the right, it’s different. When you’re nearly the best you can be, getting better is really hard, so the slope gets less steep--meaning that to improve a significant amount takes a lot more effort than it did at the beginning.

I totally made this figure up and the numbers don’t mean anything. But the way I drew it shows that I’m less talented than Usain Bolt in two ways. First, we start at different places. With zero training, effort, etc., he’s going to perform better than me in a race. He starts at 15, I start at 10. Second, he responds to training more than I do. His curve goes from 15 to almost 40, a 25 point jump. Mine goes up 20 points.

There are three things to notice here. First, if we’re at the same point on the x-axis, meaning our effort and desire are equivalent, then Bolt will always beat me because the red line is always higher than the blue line. Second, it’s possible for someone like me to beat Bolt, but only if I put in tons of effort and he doesn't (e.g. if I’m at 40 on the x-axis and he’s at 4). Third, if Bolt’s effort level gets above about 7, I can’t beat him. I can believe in myself 1,000% and work harder than Rocky Balboa ever dreamed of, and Bolt will still kick my butt. I’m cooked.

That’s how talent actually works. It defines your ceiling. You can get better by working hard. But if someone else has more talent and works just as hard as you, they’re going to be better than you.

Hard work is not enough

Maybe you’re thinking, come on Nate, if you worked hard enough, you could do it. Refuse to lose! This attitude is how Carl thought about majoring in physics, and it’s everywhere.

My favorite example comes from the first time LeBron James left the Cleveland Cavaliers, in 2010. The fans were irate and his “betrayal.” The Cavs’ owner, Dan Gilbert, wrote a scathing letter vowing revenge. He personally guaranteed that his Cavaliers would win an NBA championship before James did with his new team, the Miami Heat.

Gilbert explained how they would do it this way: “I can tell you that this shameful display of selfishness and betrayal by one of our very own has shifted our ‘motivation’ to previously unknown and previously never experienced levels.”

In Hollywood, the scrappy but pure-hearted Cavs would have won through sheer willpower. Here on earth, it was a different story. The Cavaliers had the worst record in their division in the next two seasons, and they set an all-time NBA record for the most consecutive losses along the way. James and the Heat won the Eastern Conference Finals in 2011 and the NBA championship in 2012. They were the best team in the league and the Cavs were one of the worst.

Here’s what happened: The Cavaliers were extremely motivated to win. But the Heat was too. And the Heat were better basketball players. So the Heat won while the Cavaliers lost.

You can refuse to lose if you want. But if the other team refuses to lose too, and they’re better than you, you’ll still lose.

Popular culture teaches us to be egocentric. After the game, athletes explain why they won or lost based on their team 90% of the time. Gatorade's old slogan was "Is it in You?" This is a good attitude to have, because you can only control yourself, so do your best. But still, the implication is that you'll win if it's in you and you'll lose if it's not. It seem to say that you are all that matters. The reality is, you aren't. When you stop to think about it, it's obvious: you matter no more or less than your opponent.

We humans remain stubbornly egocentric, though, because we don't stop to think about it, so we think about ourselves and not the competition. Here's an exchange that perfectly captures this attitude and why it's wrong, from Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. The Prime Minister of England is pleading with the current and former head of the Ministry of Magic. The Prime Minister speaks first.

But for heaven’s sake—you’re wizards! You can do magic! Surely you can sort out—well—anything!”

Scrimgeour turned slowly on the spot and exchanged an incredulous look with Fudge, who really did manage a smile this time as he said kindly, “The trouble is, the other side can do magic too, Prime Minister.”

Abraham Lincoln expressed a similar sentiment in 1865, talking about a much more real war. He said, about the rival armies in the civil war, that "Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other… The prayers of both could not be answered."

In short, hard work, motivation, and desire are all necessary ingredients for success. But if you want to be successful, they are not enough. If you want to succeed, you have to apply all of them to something where you have a high ceiling.

Follow your dreams?!

Last year a former professional baseball player came to my kids’ school and told them “never give up on your dreams.” I get that it’s inspirational. But come on, it's terrible advice. If 1,000,000 kids don’t give up on making it to the major leagues, and only 100 make it in a given year, the other 999,000 are going to very disappointed.

It's good to have dreams. But only if you don't prioritize them over school. If 999,000 kids didn't do their homework because they were fielding grounders, that'd be a tragedy. My dream was to be a professional surfer, but I sucked at surfing. I’m glad I didn't cut class when the waves were good. Some of my friends did, and none of them made a career out of surfing.

You hear the same thing from celebrities all the time. Gal Gadot, who plays Wonder Woman in the movies, says "be persistent and never give up." Again, I like this attitude. But still, countless girls and women dreamed of the role she got. Who wouldn't want to star in a blockbuster movie where you're hired because you look like a goddess? Most of those dreamers should give up, despite what she says, because there's no way they're going to get the role over her. If you audition against Gal Gadot, she's going to crush your dreams.

J. S. Bach was way less enlightened than Gal Gadot. Here's what he said: "I was obliged to work hard. Whoever is equally industrious will succeed just as well." Ha ha, Bach, you old jokester! Seriously, it's tempting to believe this. The problem is, there was probably some guy who lived down the street from Bach, maybe named Rach, who did work just as hard. There have undoubtedly been thousands, if not millions, of musicians who have, without succeeding as well as him.

If you asked Rach for a quote, he'd say "Whoever is as industrious as Bach will end up like me, manufacturing shoe leather for two Marks a month and eating cabbage three meals a day. Screw you, Bach, you lucky, talented bastard!" But no one ever asks the Rachs of the world for quotes. If one in a thousand people who follow their dreams meet with success, and you interview them all, you'll see that following your dreams doesn't work that well. But that's not how it works. We only read quotes from the successes, so we get a very warped view of how following your dream works out.

I honestly like the "hang on to your dreams" attitude if it doesn't go too far. But sometimes it does. I had a friend who was really good at basketball. He was an amazing ball-handler and passer. He was tough. But his talents didn't translate well to the Division 1 college game: He was short and slow and he couldn't shoot especially well. He was recruited to play at Harvard, and he was all set to go. But then a coach at UCSB told him if he walked on, he might get a spot on the team. At the time UCSB was a lot better than Harvard. So he enrolled at UCSB. He went to tryouts. And he got cut on the first day.

If you follow your dreams too far, they can hurt you. (Also see the great SMBC comic path of a hero.)

Talents are specific

The good news is, you can be bad at one thing and really good at another. Take Michael Jordan, for example. He is arguably the best basketball player in history. You’d think he’d be a great baseball player, too. He was good enough to play in the minor leagues, which is impressive. But he wasn’t great. And he was an absolutely terrible owner/GM. Absolutely terrible.

Society seems to think if you’re good at one thing, it means you’re good at everything. That’s why former military personnel, with no experience in education, are hired as school principals. And why we think people with business experience (who are good at selling stuff) will be good at politics (where you don’t sell stuff). And on and on.

There are traits that help in a lot of ways, such as intelligence or coordination or self-control. But there is a huge range of talents within any given person. If you’re human, you’re good at some things and bad at others.

You have to try a lot of stuff

You have a high ceiling for something. But you might not know what it is. So if you want to be good at something, the first step is to try a lot of things. Be patient and let something you’re good at choose you. This is true for everything where performance matters; instruments, sports, academic subjects, and so on. Even occupations.

I think of it like digging holes. If you want to dig a deep hole, here’s my advice: Go out into a field and try digging in a variety of spots. Keep going until you find a spot where the soil is nice and soft, where there aren’t too many big rocks. That's a place where success is easy for you. Dig there and you’ll be able to dig deep.

If you just choose a spot and start digging, you won’t “waste” time at the start walking around trying different locations. That might seem appealing because you’ll be making progress while other people are testing different spots out. But chances are, unless you were lucky enough to the right spot by chance, that the digging will be tough, and you’ll have to fight for every inch. When you’re hitting rocks and going slow, you’ll look over at your friend digging in an easy spot and you’ll be jealous. You’ll wish you had found a good spot. (You could end up like the violin prodigy who missed her true calling.)

The best way to develop your true talents?

Here’s the bottom line. Start out as a generalist. That means try a lot of things. See what you’re good at.

Your friends who are already specializing will tell you that you’re wasting your time. Worse, you’re letting basketball get in the way of soccer, or you’re letting your psychology course get in the way of your math concentration, or whatever. Don’t listen to them.

When you find something you’re good at, you’ll be glad you were patient.

This isn’t always possible. If you’ve got responsibilities and need to make money now, taking time to explore careers, doing unpaid internships, that isn’t going to work. But if you have the luxury of trying a variety of things, do it.

What do I do once I find my niche?

What do you do after you find your calling? The obvious answer is, start to specialize. Put all of your energy into it so you can be the best you can be.

The obvious answer is wrong.

Being a generalist isn’t just good because it helps you find your true calling. It’s also the right way to get good at your true calling. Generalists actually improve more than specializers, at least up to a point. If you want to get good at guitar, you should play some piano (and some tennis).

I won’t try to convince you of that today. But I will recommend Range, the new book by David Epstein. He’s the author of one of my all-time favorite books, The Sports Gene. I haven’t read Range yet, but I can’t wait. It’s all about why generalists flourish, and how you can too.

If you like this, check me out on Twitter.