Persuasion

Laura (and Emma) and Mary and I

Mary Tyler Moore’s influence on me was subtle but significant.

Posted January 30, 2017

Mary Tyler Moore’s death in January produced an outpouring of tributes from her show-business colleagues and fans around the world. While I admired Ms. Moore, at first I didn’t think she had much of an influence on my life. When I settled down to read the obituaries and think about Moore’s two most popular television characters, however, I realized I could not have been more wrong. In different ways, Laura Petrie and Mary Richards each left an imprint on my own character.

I was a child when “The Dick Van Dyke Show” was on the air, but I remember it well because it was my parents’ favorite program. My father, who traveled frequently for his job, would try his best to be home to watch it with my mother. In my child’s mind, Rob and Laura Petrie were slightly younger versions of my parents.

My mother was a slender, brown-eyed brunette, like Laura, and my father often donned a cardigan over his dress shirt and tie when he got home from work, just like Rob did. There was no ottoman in our living room for my father to trip over or avoid, as there was at the Petries’ home, and my father did not write for a national television show in New York. But my father was witty and had been in the U.S. Army, like Rob; my mother had lived in New York in her twenties and when I was young she stayed at home during the day, like Laura. So I found enough similarities to make me think that “The Dick Van Dyke Show” was an idealized version of my parents’ life.

Even as a child, furthermore, I was aware that brown-haired Laura was considered attractive. Since I had inherited my mother’s coloring, this knowledge gave me hope in a culture that I already knew preferred blue-eyed blondes as the ideal of feminine beauty.

In 1966 “The Dick Van Dyke Show” ended its run, my mother took a full-time job, and I transferred my affection for women television characters from Laura Petrie to Emma Peel in the British import “The Avengers.” Expertly played by Diana Rigg, Emma Peel was a slender brunette, too, but she wore a leather catsuit, had a fascinating, mysterious profession, and held her own in intelligence and wit with her male colleague, John Steed, played by Patrick Macnee. To top it off, she was British, which in my mind made her infinitely superior to American women. Emma Peel was just the role model I needed as I navigated the dangerous shoals of junior high. Family photos from those years show that I even styled my hair in the long brunette flip Emma Peel wore.

By 1970, when “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” made its debut, I had ceased looking for role models on TV. Also, the show ran on Saturday nights, and by then I would not have been caught dead watching a TV show with my parents on a weekend night. During its run I finished high school, went to college and started graduate school—all without seeing more than a few episodes of Mary Tyler Moore’s second great television series. Mary Richards, a single thirty-something professional woman, was too young to remind me of my mother and too old to remind me of myself.

And yet such was the impact of the show on popular culture that I could not help but be influenced by the character of Mary Richards. In the late 1980s and early 1990s—more than 10 years after the show ended—I was divorced, in my thirties, living on my own in a new city (Honolulu, of all places) and working as a journalist. True, I was in print journalism and not in television, but I was experiencing my own version of Mary Richards’ life nonetheless.

I remember moving to a new apartment in Honolulu after I was hired by the morning newspaper—several steps up on the salary ladder from my previous magazine job—and being thrilled that it had a pass-through counter from the kitchen to the living room, just like Mary Richards’ Minneapolis apartment. And as I grew more comfortable in the big-city newsroom where I worked, my colleagues discovered I had an uncanny ability to mimic certain key phrases of both Mary Richards and Laurie Petrie.

The first time I somewhat off-handedly said “Oh Mr. Grant!” to a fellow reporter, I heard delighted guffaws from several other reporters seated nearby whom I had not even known were listening. After that, during times of stress—which were frequent in the daily news business—colleagues would occasionally request that I reprise my “Oh Mr. Grant!” impression. In the spirit of collegiality for which Mary Richards was famous, I would happily comply. Sometimes I would follow up with a favorite scene from “The Dick Van Dyke Show”—usually, the episode where Rob misses his wedding ceremony because his Army jeep breaks down and Laura says, through breathy tears, “You jilted me!” It, too, was a hit with my fellow news jockeys.

To smooth my way in the newsroom's often combative atmosphere, I tried my best to be as nice as possible to everyone I worked with—another similarity between Mary Richards and me. But I did not foresee the unintended consequences that could result. One day, the assistant to the paper’s editor came to my desk and gravely informed me the editor wanted to see me. Assuming he was going to criticize me for some unknown infraction, I went with great trepidation to his office—a domain reporters rarely entered.

The editor had recently arrived in Honolulu from the Midwest, and he still seemed out of his element. Instead of admonishing me, as I expected, he invited me to sit down, which took me by surprise. Then he said, by way of introduction, “I understand you’re the only one in the newsroom everybody likes.” As I looked at him in confusion, wondering where this conversation could possibly be heading, he swiftly added that he thought this made me the perfect person to head up the newsroom’s United Way fund drive that year. In retrospect, it was a classic Mary Richards moment.

As dumbfounded as I was, I nonetheless accepted his request (not that I really had a choice). But as I spent the next month trying to extract contributions from my chronically cash-strapped and occasionally surly colleagues, I came to wonder whether being universally liked was a goal I should continue to pursue.

There was one key area, however, where Mary Richards’ character had it all over me. As I watched clips from the show last week, I came across one in which Mary discovers she is being paid $50 a week less than the person who previously held her associate producer job—a man. When she asks her boss, Lou Grant, to explain this inequity, he casually replies, “Oh! Because he was a man.”

When Mary responds, “Well, Mr. Grant, there is no good reason why two people doing the same job in the same place shouldn’t be making the same—,“ Lou cuts her off, saying the man had a family to support and she doesn’t. After thinking for a moment, Mary demolishes this argument, noting that financial need has nothing to do with salary levels.

Their conversation is interrupted, but at the end of the show, Lou says she is right: “There is no reason why you should be making $50 a week less than the person who had that job before.” Mary is thrilled until he adds, “So I’m raising you $25 a week.”

Holding her ground, Mary responds, “Uh, well, Mr. Grant I’m not sure you fully understand the principle involved here.”

Lou's response is, “The whole $50, huh? Right. OK, I’ll try to get you $50 a week more.”

Reporters at my newspaper were covered by a union and received annual salary increases under the union contract. But they were not barred from asking for merit increases. In my 10 years in my newspaper job, however, I never summoned the courage to do so. I learned there was a gender gap in some newsroom salaries; I also learned I was paid less than a female reporter who was hired years after I was and had less experience. I worked hard and won several journalism awards during my time in Hawaii, so I could have made a strong case for a merit raise. But the thought of verbally tussling with the paper’s contentious, generally demeaning upper management was so distasteful that I never bothered to approach them.

After I left the paper to move back to the mainland, I had lunch with a former newsroom colleague who asked me if I had any regrets from my time there. I didn’t have to think long before I answered. “I didn’t stand up for myself,” I said.

Still, I like to think that Mary Richards might have been proud of me in the end. In the job I took after I returned to the mainland, I discovered I had a lower salary than a male colleague in a similar position who had been hired after I was and had fewer responsibilities. This time, I went to my boss, explained the inequity and told him in no uncertain terms that I wanted a raise. Like Lou Grant, my boss eventually came through for me, and I in turn told my “It’s never too late to stand up for yourself” story to other women in my office.

And so I now want to join with thousands of other fans and say a fond thank-you to Mary Tyler Moore. As Laura Petrie, you brought verve, sparkle and sex appeal to the character of the stay-at-home wife and mother. As Mary Richards, you had spunk—the word Lou Grant famously used in your job interview with him. But you also had smarts and grace and kindness, and you showed your female viewers how to deftly maneuver in the treacherous minefield of the male-dominated workplace.

By creating such a memorable character, you influenced women like me who didn’t even watch your show except for every now and then. In your honor, the least I can do now is try to catch up on a few episodes. And who knows? I might discover a number of other ways in which Mary Richards shaped my character without my even realizing it.

Copyright © 2017 by Susan Hooper

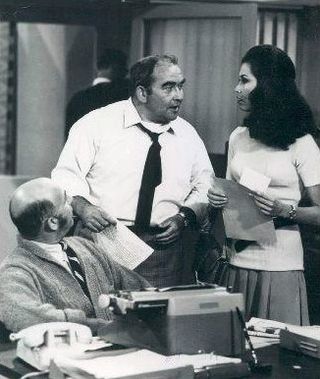

"The Mary Tyler Moore Show" Photograph by CBS Television via Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain.