Among the Cassandra–like warnings of future calamity threatening us, one, in particular, has caught my attention: “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” This is the title of a recent article in The Atlantic by academic psychologist Jean Twenge. (1) Professor Twenge identifies a laundry list of ominous signs in the behavior of modern youth (dubbed by Twenge the internet generation or iGen) that she traces to the growing use of the internet and lives dominated by social media. I bring a quite different perspective to this phenomenon that grows out of my work as an anthropologist who has studied childhood and youth across the globe. From my wider lens, I can confirm the portrait now being painted of the iGen but will argue here that the internet is far more effect than cause and that the roots of the iGen must be sought in the mid-20th century as Western society became increasingly child-centered. Our preoccupation with children has become so all-encompassing that our youth are afraid to leave their WiFi enabled, velvet-lined nests.

Twenge has also authored a fine book with the title iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. (2) Dr. Twenge has done a marvelous job of reviewing and analyzing the available survey data on contemporary adolescents. Her prose is clear and jargon-free, and she makes a very convincing case for her arguments about the primary characteristics of the upcoming generation—born between 1995 and 2012. This is not a review, however, but rather an attempt to link ideas that I’ve written about (3, 4, 5) to the so-called iGen. Again my primary goal is to show how the foundation for the iGen lies in very gradual changes in culture as it affects children.

My entry point into this discussion was the remote central Liberian community of Gbarngasuakwelle. I went there to study and document the lives of children in an unacculturated tribal society where schools and missionaries had not yet penetrated. As I later realized from my readings, childhood in Gbarngasuakwelle looked a lot like childhood around the globe in similarly isolated towns, villages, and hamlets. Later, I realized the historical record of children’s lives prior to the late 19th century revealed many of the same features. But I was forcibly struck by the great contrast with the nature of childhood in Beaver, Pennsylvania—where I (while alternatively caring for my infant daughter) hunkered down to turn my notes into a dissertation titled Work, Play and Learning in a Kpelle Town. In simplistic terms, the African children I observed were far more independent. At an early age, they were expected to be undemanding--especially after weaning--and to “hang out” and play with peers not adults. When with adults, they were to pay attention and model themselves on mature social behavior and speech. They should attend to tasks essential to the family’s survival and comfort and, in effect, educate themselves. Much of their play mimicked adult work and clearly served to practice and improve skills they’d soon be expected to employ for the greater good. That is, children were eager to pitch in and help out and were obviously gratified when their efforts actually accomplished a useful piece of work. These volunteer efforts turned soon into their “daily chores.” And speaking more broadly, it is true that, excepting among elites, children everywhere are bona fide members of the domestic labor force from an early age (6).

From weaning to at least middle childhood, Kpelle children were largely ignored by adults, any one of whom was free to chastise or even beat a wayward child. While their basic needs for food and shelter (clothing optional until 5) were met, they certainly couldn’t expect any special treatment—in contrast to the elderly. No one worried about a child’s preferences or whether they were happy. A crying child was likely to be smacked by its mother or sent off in company with an older sibling. Children’s lives were certainly not scheduled. They weren’t “called for dinner” or “sent to bed.” Birthdays went uncelebrated because birth dates weren’t noted, and it wasn’t until the child was on the threshold of adulthood that they would become the subject of ceremony such as the initiation—a painful rite of passage. Children were not gifted with toys other than old, worn artifacts, which they, nevertheless, found very satisfying as toys. Children were also very inventive at turning found objects and scraps into recognizable miniatures, especially cars (although they may have seen a car only once in their lives). Adults largely ignored children at play unless they were obnoxious or threatened property. No adult volunteered to teach or coach a child to improve his or her performance. There were no designated “play grounds” per se. While play groups that included 2-4 year-olds were expected to remain within hearing of a nearby adult, older children had free reign to travel through the bush (even though poisonous snakes were not uncommon), to play variations on “Tag,” or to practice their foraging skills.

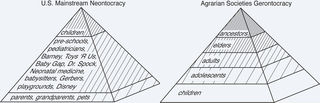

As I prepared my ethnography of Kpelle childhood for publication in 1996 (3), I realized that I might capture this stark contrast between the “tribal” model of childhood with the model found in the contemporary, middle class with a simple dichotomy.

Figure 1 Neontocracy vs Gerontocracy

I have used this figure in my writing, in visiting lectures and, of course, in my classes to good effect. The basic message is that, in the Gerontocracy—which is or was the prevailing social structure—status and privilege come with age. Older people are respected and appreciated for their knowledge and skills, accomplishments, fertility, relative wealth, and social connectedness--among many other attributes that accrue over a lifetime. Ancestors demand particular obeisance because, at death, they enter the netherworld and can intervene—for good or ill—in the lives of living kin. Relative status is most strikingly revealed in burial practices where the elders are buried with ceremony and memorialized with grave goods and grave markers or in a household shrine. Deceased children until five or even ten in some cases are not given any funeral rites or a formal burial plot but disposed of inconspicuously.

The Neontocracy can be traced to the Victorian era (19th c.). Among the growing middle class, children were sentimentalized, needing “protection” rather than being “exploited” for their potential as workers. This trend continued as “the market price of a twentieth-century baby was set by smiles, dimples, and curls.” (7, p. 171) Still, the norms for how children were viewed and raised changed slowly. For example, modern parents take it for granted that they should play with and otherwise entertain their infants. But in 1914, the US Government Children’s Bureau published an Infant Care Bulletin in which “playing with the baby was regarded as dangerous; it produced unwholesome pleasure and ruined the baby’s nerves. Any playful handling of the baby was titillating, excessively exciting, deleterious. Play carried the overtones of feared erotic excitement.” By 1940, playing with an infant was finally endorsed in the Infant Care Bulletin (8, 172).

Most importantly, for this essay, is the whopping increase in the share of the family’s resources now allocated to children. This is reflected in parents investing far more time in children: shopping for them; dressing them; schlepping them; playing with them; assisting them with schoolwork; attending their games; managing their busy schedules; etc. The internet now blossoms with advice to combat “parental burnout.” The price tag has also skyrocketed. Consider the costs of: Assisted Reproduction Technology; neonatal medicine; overseas adoption; cosmetic dentistry; trunk-loads of toys; furnishings including electronic media (iPhones and Xboxes); child care and; school and college tuition for starters. The average cost of raising an iGen child to age 18 has reached $250k, according to USDA statistics. These costs have gone up even as the child’s contribution to meeting them—via wage employment —has gone down. Helpful websites now offer formulae to assist the prospective parent in calculating whether they can afford to have a child.

My wife and I are baby boomers. We grew up in rural Missouri and Pennsylvania in the 50s and 60s. There were hints of the Neontocracy. We got occasional treats, birthday cakes and presents, and faithful visits from Santa. Both of us were sentimentalized in the Victorian manner to the extent that once every few years our parents dressed us up for a photograph, which would be printed and kept in an album or, very rarely, framed and displayed. However, our retrospective visits to our past reveals more Gerontocracy than Neontocracy. Chores were expected; one of my nicknames was “the lawn mower kid,” and Joyce, on the family farm, had a myriad of responsibilities. My clothing was purchased—without any input from me—annually in August from the Sears, Roebuck catalog. Joyce made her own clothes. We both went to work in the summers until graduating from college. My first job at 15 was laboring in an electro-plating factory. Joyce clerked at a Feed Store from age 16.

But we both agree that the most significant change that occurred from the time we were young and today is the relative standing of children. We were sternly trained to respect and defer to adults, including parents, of course. Failure to do so would shame the family and arguing or “talking back” was tantamount to mutiny to be punished accordingly. We knew our place in the social hierarchy, and it was definitely not at the apex of the pyramid. In terms of accomplishments, wealth, security, experiences, wardrobe, privilege, respect and socializing, we had nowhere to go but up. The full-blown Neontocracy has been realized only in the last 25 years. Now, children are unequivocally on the top, the beneficiaries of incredible attention and largesse. It is clear to me from Twenge’s review that members of the iGen—who’ve grown up in the Neontocracy—have nowhere to go but down.

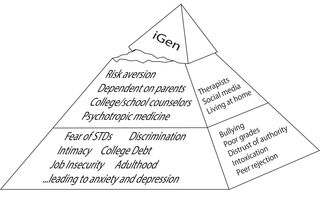

As Twenge argues, one of the most noteworthy trends among the iGen is the deliberate forestalling of cultural markers of maturation. Parents and schools collaborate to wrap children in “cotton wool,” protecting delicate bodies and emotions from any hint of trauma or stress from their schoolwork, play, or peers. They are not burdened with chores. They are the “Snowflake Generation.” (9) As Twenge notes, these extraordinary precautions, which began in elementary school, have “grown up” with the children so that college students now expect the institution to provide various watchdogs and “safe spaces” to insure their protection from all manner of unpleasant experiences. iGen members fully expect that families and schools will respect and cater to their desires and choices. Family meals have given way to individual servings so that children can customize their own diet.

Twenge notes recent, dramatic declines in adolescent engagement with precursors to adulthood like paying jobs after school and during summer vacation, dating, sex, getting a driver’s license, drinking and “rebelling” against parental authority.[JK4] And adulthood, as measured by milestones like independent living, a permanent job, marriage, and family formation, is put off indefinitely. Adolescents are no longer transitioning from their families to a primary association with a cohort of peers; indeed, college students resent having to share “their space” with roommates. They “hang-out” with their parents, not their buds. With cell-phones, Instagram and texting, parents know where their offspring are at all times and what they’re doing. Among young women at college, “exciting news” is likely first shared with “Mom.” More importantly, adolescents who experience “helicopter parenting” as children actively seek to prolong that process by consulting parents at every decision point, however, inconsequential. Parents and their children concur on the need to use college to enable a safe, well-paid profession. Nevertheless, Twenge reviews a recent survey of college students showing them scoring very high on a measure of “maturity fears.” They readily agree with statements like: “I wish that I could return to the security of childhood” and “The happiest time in life is when you are a child” and disagree with “I feel happy that I am not a child anymore.” (2, p. 45)

In Twenge’s own research she queries students about these trends. When asked about dating and sex, respondents spoke about the risk of STDs and the conflicts and stress of intimate relationships. They were concerned about losing their individuality. “Dealing with people, iGeners seem to say, is exhausting.” When asked about employment, respondents noted the routine and boredom and the need to conform to someone else’s schedule, dress code, and so on. When asked whether the need to work was obviated by a generous allowance, they admitted that parents would buy them or give them the money to buy whatever they wanted. Similarly, driving oneself not only entailed risk, but was unnecessary as parents drove them everywhere they needed to be. Twenge found from her iGen respondents that “being an adult involved too much responsibility. When they were children, their parents had taken care of everything and they’d just gotten to have fun.” (2, 46)

Figure 2 iGen Pyramid

In short, for our offspring, life is a bed of roses (the petals, not the thorns), and they are increasingly unwilling to get out of bed as the “Failure to Launch” syndrome clearly shows. (5) You would think, given this scenario, that they would be consistently upbeat and cheerful. But no. Twenge devotes an entire chapter to what she refers to as the “New Mental Health Crisis.” The percentage of high school students who claim to be happy has fallen sharply from a peak in 2011. Depression among youth is rising as they agree with the statement “My life is not useful.” In creating a comfortable, safe, undemanding, indulgent bubble for youth, we are stranding them on an island where they begin to feel lonely and useless. The greater the feeling of comfort and security, the greater the eventual anxiety about the inevitable exit from the bubble. Rather than rushing to embrace the world and all its wonders—which characterized baby boomers (think Peace Corps)—those in iGen use social media and video games to shore up the barriers erected to keep the world at bay. Twenge’s subjects “Like their iPhones more than actual people.” (1) The peak of the social pyramid begins to look less like a penthouse aerie and more like a precarious perch.

References

(1) Twenge, Jean M. (2017) Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? The Atlantic, September.

(2) Twenge, Jean M. (2017) iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. New York: Atria Books.

(3) Lancy, David F. (1996) Playing on the Mother Ground: Cultural Routines for Children’s Development. New York: Guilford Press.

(4) Lancy, David F. (2015) The Anthropology of Childhood: Cherubs, Chattel, Changelings 2nd edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(5) Lancy, D.F. (2017) Raising Children: Surprising Insights from Other Cultures.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(6) Lancy, David F. (2018) Anthropological Perspectives on Children as Helpers,

Workers, Artisans and Laborers. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

(7) Zelizer, Viviana A., (1985) Pricing the priceless child: the changing social value of children. New York: Basic Books.

(8) Wolfenstein, Martha (1955) Fun Morality: An Analysis of Recent American Child-training Literature. In Mead, Margaret and Martha Wolfenstein. Childhood in Contemporary Cultures (eds) pp.168-178. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

(9) Fox, Claire (2016) “I find that offensive.” London: Biteback Publishing