Anxiety: Is It an Illness?

Anxiety is a normal, necessary, and useful mental state of apprehension about what might, or might not, lie ahead; it is typically accompanied by an array of unpleasant physical sensations—jitteriness, pounding heart— to grab our attention. Its function is to alert us to the possibility of danger and urge us to make necessary preparations to protect ourselves.

Occasional bouts of anxiety are entirely normal and one of the unavoidable costs of being—and staying—alive. However, sometimes worries get out of control. They intensify or persist, overwhelming the capacity of the brain to rationally consider the hypothetical danger. Or the brain may get stuck on high alert, repeatedly enacting its bias toward negative information by searching for catastrophe everywhere it looks. Under those conditions, anxiety can get in the way of everyday functioning or cause unnecessary distress, at which point it is designated a disorder.

On This Page

Anxiety, in which normally innocuous situations can trigger outsize negative emotional expectations, is a natural aid to survival, a core part of the human defense system. Every person alive today is the beneficiary of a brain with a strong enough capacity for worry to have enabled early identification of and triumph over threats that arose over the eons of human existence. In moderate amounts, anxiety is a boon to daily life—it stimulates people to overcome challenges and heightens performance. Studies show that anxiety involves activation of specific brain centers—such as the anterior insula—that boost the ability to predict future harm and learn to avoid it. People naturally differ in the threshold and degree of activation of the brain nodes that play a role in anxiety, Experience, too, can change the settings: A history of early harm can lastingly alter the threshold of reactivity of such brain centers, making people particularly anxiety-prone or easily overwhelmed with worry.

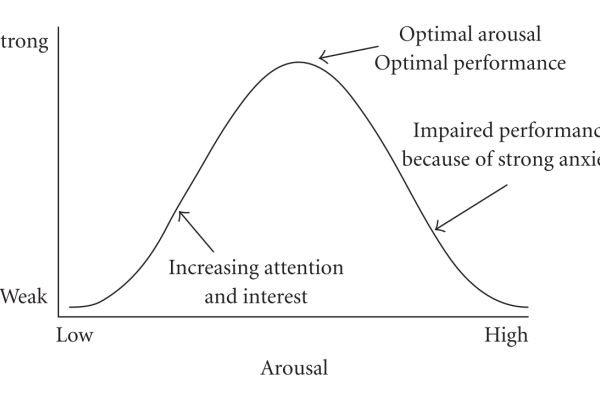

Anxiety becomes a disorder when the worry about possible dangers (“Will I catch COVID-19 if I touch a doorknob?”) or negative outcomes (“If I go bald, will my girlfriend stop finding me attractive?”) arises for no discernible reason, or it is disproportionate to the situation, or lasts beyond moves to solve any possible problem, or the worry or physical symptoms prompt you to avoid situations that may trigger symptoms. While a little bit of anxiety can boost motivation and performance, excessive anxiety interferes with activities and performance, sometimes to the point of incapacitating people.

Anxiety is marked both by physical signs (racing heart, fast breathing, difficulty concentrating) and mental ones (excessive imagining doomsday scenarios), and the bodily symptoms and worrying thoughts feed each other, creating a vicious spiral that make the thinking feel hard to control. Here’s one of the great ironies of anxiety disorders: Although there are effective treatments, people may fail to seek help because they are embarrassed about the things they worry over.

The threat detection system is a basic part of our ancient brains. In order to stay alive, every animal must be able to detect threats posed by the environment and from within the body itself. The threat detection system—which starts in the brain’s amygdala—has many parts in which people perceive, pay attention to, emotionally react to, understand, and act on signs of present or potential dangers. Fear is the response to manifest threats; anxiety is the normal reaction to potential ones, when the thinking brain (the prefrontal cortex) has time to discount or defuse possible problems.

Anxiety becomes a clinical condition when there’s a malfunction in any part of the system or the complex circuitry that connects them or when precautions taken against possible problems fails to deactivate the alert system. For example, researchers find that people with anxiety disorders are overly oriented to noticing negative possibilities (shadows become definite monsters, that frown on the boss’s face means you’re about to be fired) and often can’t disengage their attention from them.

Neurosis is a term coined in the late 18th century to denote illnesses for which no physical cause could be found. More than a century later, both Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung popularized the term to denote a broad class of psychological functioning; it covered an array of ways people maintained contact with reality but experienced inner mental conflict or anguish. In Freudian theory, neurosis is the is outer expression of some unconscious desires that are often deliberately repressed because they are socially unacceptable,. Psychoanalysis was aimed at discovering the presumed hidden conflict driving neurosis.

The term no longer has any agreed-on meaning in the mental health world—it was officially discarded as a diagnostic term in 1994. But it is still occasionally used to denote a way in which people engage in overt behavior that is ultimately nonproductive (nail-biting, for example) in response to uncomfortable thoughts or feelings they may or may not be aware of. Such behavior is deemed neurotic. The term most closely overlaps with a tendency to anxiety, the source of which people may not always be fully aware of.

Although no animal shows all the features of the mental health problems that humans are heir to, some animals show behaviors—hypervigilance, for example—that are analogous to one aspect or another of such disorders, including anxiety, or share physiological features that underpin human anxiety. Fear is an emotion closely related to anxiety, and, as every dog owner has discovered during thunderstorms or fireworks displays, animals exhibit distinctive responses to fear stimuli. But anxiety is typified by both physical features, such as jitteriness and disturbed sleep, and cognitive features, such as imagining the possibility of failing a test. Even though nonhuman primates have much of the same neurobiology that is involved in human anxiety, much about emotionality in all animals is inferred from behavioral actions.