Adolescence

Parenting and the Amazing Teen Brain Part 1

Why you should align parenting with neuroscience and teen neurobiology.

Posted June 26, 2013

This is the first in a series of articles on the teen brain, based on a presentation given at Miami Beach Senior High School. If you are the type who wants to skip straight to the tips, don’t worry. The final article will culminate in a summary of all the specific tips for parents of teens. For those who want a deep dive into the details, start here!

Teens. If you have just one in your household, you’ve got challenges that might make the Terrible Twos seem like a cakewalk. Their behavior may, at times, appear inscrutable, but teens are doing exactly what they need to do to. Ultimately, they are on a pathway to leave home, which is a HUGE developmental task.

Think of going from driving on all surface roads, where you can go anywhere and see everything, to creating super-fast, super highways. You get there faster, but you can no longer get to everywhere from anywhere. Hence, the end of brain re-organization is correlated with the end of schooling. Our brains are no longer as flexible as before, but they are faster and more efficient. The longer this ‘redesign’ process takes, the smarter and more competent your teen will become.

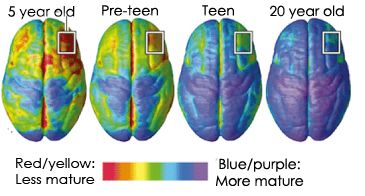

Brain development from childhood to young adult

Research has shown that brains don’t look like an adult brain until the early to mid-twenties, so if your child is under 25, you are still in the teen zone. As children, teens, and young adults, our brains are wired for maximum absorption, but the brain has not yet developed the areas of the brain that are optimized for higher-level understanding. As we develop our brains into the adult form, we transition from being optimized for input to being optimized for understanding. The adult’s capacity for understanding is why many find they have a greater ability to understand the writings of Shakespeare that may have stumped them as a teen. While a teen is optimized for what, the adult brain is optimized for why.

(Here is your challenge to get involved in your teen’s homework—you’ll be surprised at the shortcuts to understanding you will be able to provide!)

Scientists have conducted many brain scans of kids, teens, and young adults to see where, how, and when the brain changes from the juvenile form to the adult form. What we’ve learned is that gray matter peaks and then declines in early childhood, but then increases again in the teen years. Gray matter makes up the outer layer (also known as the cortex) of the brain and is primarily responsible for memory and conscious thought. Finally, as the teen brain develops into the adult brain, there is a decline in gray matter. This decline is a natural part of maturation, and it is due to the brain becoming more and more efficient, therefore needing less gray matter to get the job done.

To complicate matters further for the teen brain, all the parts don’t develop on the same schedule, and males and females develop on different schedules as well. Primal functions, such as movement and sensory processing, are the first to mature (with boys maturing faster than girls in these areas). What we think of as ‘higher’ functions, such as impulse control, long-term planning, emotional control, and risk-assessment (the aspirational hallmarks of an adult brain) are on a much slower maturation schedule (with girls maturing faster than boys in these areas).

Parents and peers play a crucial role during the developmental phases of the brain. The parts of the brain that are consistently accessed get strengthened, while the parts not used are pruned away. The teen brain is on a mission to build up what is needed and get rid of what isn’t, which is why the final stage of brain maturation is a decrease in gray matter in the early twenties. This time is the window for pushing teen development, as the goal is to push the brain to develop as many connections as possible. Connections are built and reinforced through repetitive exposure to new physical skills, mental skills, and life experiences, with a healthy dollop of love, affection, and support from you. That’s right, parents do matter!

Think about all the outwardly visible physical changes you’ve seen in your child, and be aware that massive changes are going on in the brain too. The goal of teen years is a radical redesign of the brain. Processing is actually being shifted to entirely new anatomical structures.

The teen brain deals with emotion very differently from a child or adult. The teen brain is experiencing complex emotions (enhanced or hindered by hormones, depending on context) for the very first time; not only do teens lack the life experiences of the adult to handle complex emotions, but the areas of the brain that handle teen emotion are not fully developed yet. Teens are hit with a double-whammy when faced with strong or complex emotions; they don’t know how to wield them, and even if they did, they wouldn’t have the brain structures in place to pull it off as an adult brain would.

So here we have our teen, faced with a rapidly changing brain, hormones at comical levels, an uneven maturation schedule of mental functions, and lacking the adult’s long-view of experience, plus nearly ubiquitous sleep deprivation. The teen brain finds you to be inscrutable. Lacking the brain development and experience, they can’t yet fully comprehend how adults make decisions. No wonder we can drive each other so crazy.

In the meantime, your teen will have a teen brain. Over several articles, I will explore the teen neurobiology in detail, but here is the best single, succinct piece of advice I can give you:

- The louder your teen gets, the quieter you should be; the angrier your teen becomes, the gentler you should become; the meaner your teen behaves, the kinder you should be.

The best way to manage the intensity of the teen brain is to provide a consistent umbrella of calm—even when calm is the complete opposite of what is going on inside your brain.