Resilience

What Do We Know About Resilience in the Wake of Disaster?

We have evidence of what works, lessons learned to guide us.

Posted March 20, 2020

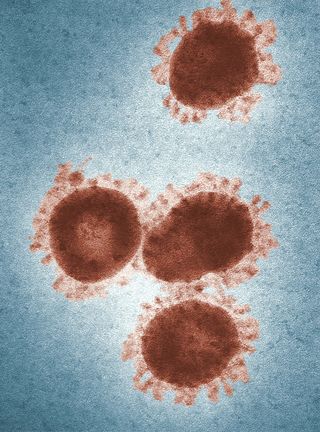

Our country, our world, is besieged by a disaster, one that has yet to deliver its full, awful impact on lives, communities, and economies. The coronavirus, and the COVID-19 disease it unleashes, is unprecedented. These are circumstances that beg for human resilience: a capacity built into our nature for survival.

But resilience, and the recovery it will bring, take intention, work, and patience—all of which will be tested in the face of uncertainty and pervasive sacrifice and suffering. Our "fortune," now, is "outrageous"—yet the future remains in our hands.

Hamlet wondered, "Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer/The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,/Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,/And by opposing (my emphasis) end them."

This is a rhetorical question, because fighting to survive, to get through and past this disaster, will happen. But how? What have we learned from past disasters in the U.S., like 9/11, Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina, power blackouts, tornadoes, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and so on? What works in promoting resilience and achieving recovery?

While every disaster—and every community and governmental entity—is unique, there are clear, universal lessons to guide us. My comments derive from past experience leading mental health responses to disasters in New York City and New York State (1, 2). What works are:

First, a set of organizational mandates, including: an unfaltering urgency of response; clear accountability; continuous coordination among the myriad of agencies and organizations charged with responding to the disaster, which means live-time data driving and optimizing responses, ideally from a "command and control" center; responsible media coverage; and preparation for the return of what has happened or the next disaster, since it will come. As essential as those are, they fill media and policy discussions; may we be guided by them, at every level of government and non-government organizations.

That leaves the human responses, which are our focus here. These are more immediate to all of us. The elements of our humanity that enable bearing, or not, the misfortune that has befallen us and our world. Here, we have evidence, lessons learned, of what is protective to we humans, and what poses a greater risk of disease (physical and mental) and disability.

Protective factors include: the good fortune of having a supportive family and friends—the power of attachment (3) has been shown to make for longer and healthier lives; over-communication because isolation fosters loneliness, which is bad for the human condition; we need to sustain regular, even frequent contact with others who care about us and whom we care about (which with the coronavirus pandemic will need to use every form of virtual contact—phone, email, web-based video calls like Zoom, Skype, FaceTime, etc.); housing and food "stability"—knowing there will be a roof over our heads and food on the table; permission that we must grant ourselves as a social norm, that talking about distress (as opposed to bottling it up) is beneficial—one tag-line we used after 9/11 was "Even Heroes Need to Talk"; employment, or the prospect of it returning as the disaster abates; faith (both spirituality and religion) (4); and hope.

Risk factors include: a pre-existing or active mental or substance use disorder (as well as excessive drinking or drug use); poverty (often associated with intake of high-calorie foods and drinks of low nutritional value); limited education; physical inactivity (a sedentary lifestyle); unemployment, with little prospect for future work; domestic and neighborhood violence; and lack of access to effective health and mental health care (5).

How can we optimize what is protective of our health and well-being?

In The Harvard Study of Adult Development (6), among the longest longitudinal studies of adult life (it began in 1938), researchers asked: "What is the best predictor of a long and happy life?" The answer, for generations of Harvard students (men and women), was not fame and fortune. It was enduring and trustworthy relationships. That's the protective power of healthy attachments to others, and it plays a vital role in resilience to disasters and crises.

Attending to these emotionally sustaining relationships during this time of "social distancing" and "sheltering at home" means over-communicating. Use whatever device works best for you and those you contact. It is not the medium that counts; it's the message of being close despite the circumstances. Don't be afraid to speak your mind because "even heroes need to talk." But remember, our aim is to buoy others, which happens when we find the positive.

Far too many people will not have the security of a home or food on the table. Already, some cities are using empty dormitories and hotels, gyms, stadiums, shelters, too, to care for those most vulnerable. We can support this work by urging our elected officials to stand by and for the most vulnerable, the moral measure of a society. We can also contribute to known non-governmental organizations that serve the poor and homeless.

Faith has many meanings. It may be with religion or secular, coming from within. I like to think of faith as the conviction that God (however defined) is on your side, that the arc of fate will bend our way.

Andrew Sorkin, in The New York Times (7), proposed a wonderfully radical plan that would keep vast numbers of people employed—but now out of work because of the pandemic: He urged that workers continue receiving their pay from government subsidies to employers (required to pay their employees), enabling businesses (and workers) to survive the economic tailspin underway. Expensive? Yes. Apt to be gamed? Yes. But the alternative of a very, very long business (small and large) recovery would be far more negatively economically consequential. Being able to pay the rent and knowing a job would be there in the future are extraordinary sources of hope.

How can we take better care of ourselves, quiet the stress hormones that are pouring out of our adrenals? In five ways. One has been covered, namely sustaining relationships with those you care about and who care about you. The second and third are adequate sleep and good nutrition (like a Mediterranean diet and easy on the sugars), easy to forget or push aside, but both are restorative to our bodies. The fourth is physically moving our bodies, which is much harder if we are confined. But as long as we have internet, music, and television, we will have countless programs offering movement of all sorts. What do you like? Even 20 minutes a day can do the job.

Finally, the western world has finally come around to a variety of "mind-body" activities that are powerful in diminishing stress, lowering heart rate and blood pressure, and even protecting the insulin-making cells in the pancreas. These include yoga, meditation, slow breathing (yogic breathing, my choice in recent years), mindfulness, and Tai Chi. These are free to learn (online), but they take some practice to master, a different sort of price, priceless—as has been said.

We face an unprecedented time, a worldwide pandemic, in which no one will be spared in one way or another. Analogies are inescapable to the Great Depression, to two World Wars, and to epidemics that have taken so many lives over so many centuries. Yet we survived.

We are resilient, but it will take work. And solidarity. Kindness and patience, too, elusive virtues. Perhaps those are the "new normal"? Perhaps, but these are within our grasp, and there are far worse demands.

References

1. Sederer, LI, Lanzara, C, Essock, S, et al: Lessons Learned From the New York State Mental Health Response to the September 11, 2001, Attacks, Psychiatric Services, 62:1085–1089, 2011.

2. Sederer, LI: Are human made disasters different?, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences (2012), 21, 23–25. Cambridge University Press, 2011. (doi:10.1017/S2045796011000710)

3. Sederer, LI; Improving Mental Health, Four Secrets in Plain Sight, American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2017.

4. McIntosh, DN, Poulin, MJ, Silver, RC, et al:The distinct roles of spirituality and religiosity in physical and mental health after collective trauma: a national longitudinal study of responses to the 9/11 attacks, Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011.

5. Sederer, LI: The Social Determinants of Mental Health, Psychiatric Services, 67(2):234-235, 2016.

6. Vaillant, G: Aging Well: Surprising Guideposts to a Happier Life from the Landmark Harvard Study of Adult Development Paperback – January 8, 2003.

7. Sorkin, Andrew Ross: This Is the Only Way to End the Coronavirus Financial Panic, The New York Times, March 19, 2020.