Gender

Understanding Gender Differences in Religiosity (Part II)

How the unified approach explains why men are less religious than women

Posted November 7, 2014

In Part I of this two-part blog post, I surveyed the robust finding in the science of religion that men are less religious than women. I then reviewed the competing biological, psychological, and social explanations for this well-known, but poorly understood phenomenon.

My goal in this blog is to help readers wrap their minds around how the unified approach works to generate a consilient physical-bio-psycho-social frame, which is in stark contrast to thinking about biological, psychological, and social explanations as competing against one another in a horse race. What the unified theory allows one to do is to look at the “gestalt” of gender and then see how the various theories and empirical findings line up.

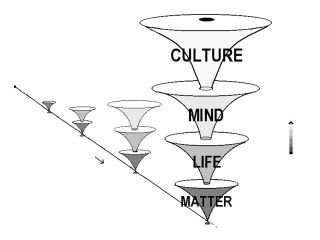

Those familiar with the unified approach know that it divides the universe up into for dimensions of complexity: Matter, Life, Mind and Culture. These dimensions of complexity correspond to the physical, biological, psychological and social dimensions of understanding in science. The dimensions of complexity emerge out of matter because of the emergence of novel information processing systems (genetic/Life, neuronal/Mind, linguistic/Culture). For more detail on how the unified approach maps the unfolding wave of Energy-Information, see here.

In addition to providing an overview of the dimensions of complexity via the Tree of Knowledge System, the unified approach offers three other ideas, Behavioral Investment Theory, the Influence Matrix, and the Justification Hypothesis to ‘knit’ together these dimensions in a way that allows for a coherent picture of human psychology. To understand human gender differences, one needs to look at gender through the lens of these three ideas. Note that, in human psychology, Behavioral Investment Theory roughly corresponds to biological/neuro/evolutionary explanations, the Influence Matrix to personality/motivational/psychological level explanations; and the Justification Hypothesis to social, human cognitive, and cultural explanations.

Gender Differences from the Vantage Point of Behavioral Investment Theory

Behavioral Investment Theory links psychology to biology. It does so by claiming the nervous system is an “investment value system" that coordinates animal behavior in accordance with evolutionary and learning history. If we want to know about gender differences from the vantage point of BIT, we ask the question: Would evolutionary pressures shape “the investment value system” of males and females in the same or different ways? This is basically synonymous with the way that evolutionary psychologists (EP) think of gender.

We would expect the “investment value system” of males and females to be similar in many ways. Both need to acquire the basics for survival, avoid dangers, manage temperature fluctuations, and so forth. So we would expect generally similar food preferences (although may be different for pregnant women, see here), both sexes should have pain in response to bodily injury which they seek to avoid, both should have sweat glands, and so on.

Although the pressures for survival are similar for the two sexes, the reproductive game is very different. The facts of physiology are such that human females invest much more in their offspring than males. This is so at the level of calories, time, effort, risk of child bearing, etc. Because human females are the more investing sex, we can make many predictions about how the two genders will differ in their basic architecture toward sex and pair bonding.

Let me give you one classic example. Given that human females must invest so much more in off-spring, we can make the clear prediction--without ever looking at any actual society or learning theory--that, on average, human males will be much more willing to engage in casual sex (i.e., sex without investment) than human females. As extensions of this claim, we can say that human males should have faster levels of sexual arousal, be willing to sacrifice and invest for sexual access, and be willing to take more risks to engage in casual sex. Notice how things like prostitution and pornography usage immediately begin to make sense through this lens.

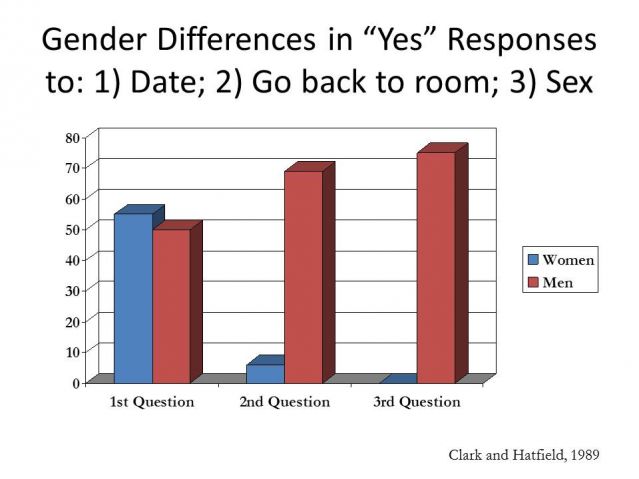

One of the most famous studies in the history of gender differences examined this prediction. The researchers had men and women who were independently rated as highly attractive go up to members of the opposite sex on a college campus who were complete strangers and ask one of three questions, all of which had the same stem, but different endings: “Hi, I have noticed you around campus and think your are attractive and I was wondering if you would…” 1) “go out on a date with me?” or 2) “go back to my room with me?” or 3) “have sex with me?” Here are the data:

Whereas equal numbers of men and women said "yes" to going out on a date, almost 75% said they would have sex, whereas not a single woman said yes to that question. The gender differences here are truly remarkable and directly consistent with basic predictions derived from a view informed by parental investment theory. There is a huge literature on gender differences from an evolutionary perspective. (For a good academic review, see here).

To fully understand gender and religion we need to consider men and women through a relational lens. And to do that, we need the Influence Matrix.

Gender Differences from the Vantage Point of the Influence Matrix

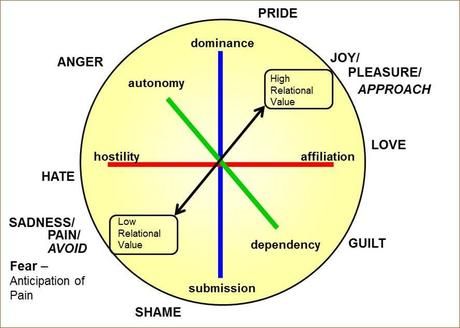

The Matrix is an extension of BIT and functions to map the human relationship system. The central variable that organizes human relating according to the Matrix is the black line. This is the Relational Value-Social Influence (RVSI) line. It refers to the extent to which an individual feels known and valued by important others. It is seen as the core human psychosocial need.

In addition to the RVSI Black line, there are three relational process dimensions, marked by the blue, red, and green lines. The blue line is the “power” line, marked by the poles of dominance and submission. The red line is the “love” line, marked by the poles of affiliation and hostility. The green line is the “freedom” line, marked by the poles of autonomy and dependency.

What does this have to do with gender differences? Look at the upper left quadrant. It is marked by the poles of dominance, autonomy and hostility, as well as the emotions of anger, hate and pride. Now look at the lower right quadrant. It is marked by the poles of affiliation, submission, and dependency, and the feelings of love, guilt and shame. Now think about archetypes of masculinity and femininity. Notice anything? The upper left quadrant, the “self” quadrant, overlaps enormously with the masculine archetype. That is someone who is powerful, independent, confident, and self-assured (and also can be angry, defiant and mean). In contrast, the feminine archetype is someone who is loving, nurturing, sensitive, and kind (and also can be dependent, vulnerable and weak). For more on how the Matrix elaborates on this, see this blog on self and other orientation.

The Justification Hypothesis

Am I saying that all human males are powerful, independent jerks and all human females are sensitive and caring but vulnerable waifs? (OF COURSE NOT!) And what about where those ideas of “masculinity” and “femininity” come from? Isn’t the case that we are all imbedded in a society that legitimizes social roles and tells us that a man is "strong" if he is defiant and he is a “stud” if he sleeps around, but a woman is a “bitch” if she is bossy or a “slut” if she sleeps around?

This is the standard caricature of the rhetorical position of those who take a gender role socialization approach to understanding gender differences.

Just as BIT assimilates and integrates evolutionary perspectives, and the Matrix clarifies archetypal relational differences, the Justification Hypothesis integrates the gender role socialization perspective. It achieves this by pointing out that people build systems of justification that coordinate and legitimize their actions and investments. Thus social groups will develop norms for men and women and reward and punish them accordingly. The flexibility and power of these systems is easy to see. Consider how different the gender roles are in Canada and the US from Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan. Or consider how much gender roles have changed in this country over the past 50 years. Or think about how much change has taken place in the “justifiability” of homosexual and transgendered orientations in the last decade. In short, the “context of justification” plays a huge role in how gendered patterns are expressed and felt. And how they develop in each individual. Whether someone develops a self or other orientation for example, has EVERYTHING to do with their lived experiences. The adult form is always a transaction of initial pre-dispositions that are shaped by rewards and punishments. And in human societies, justification systems set up and deliver rewards and punishments.

Back to Religiosity

All of this allows us to return to the issue of religiosity. Now the question becomes, given these lenses through which to understand gender, we can now ask the following: What are the broad and general dynamics that might be associated with gender differences in being religious? Staying within the Judeo-Christian Western frame for now, let’s ask the question of what are the key dynamics that would lean someone toward or away from being religious?

Religion provides conventional norms, so we would predict that the gender that was more defiant and risk-taking to be less religious. Religion supports the community, legitimizes sexual restrictions, and a family focus, so we would expect that the gender that is more nurturing, more sexually choosy, and more family-focused to be more religious. The religious experience is relational, meaning that it is the experience of relating to God that drives the subjective dimension of religion, thus we would expect the gender that is more relational in their thinking style to be more religious. There is a strong social element to religion, thus the more one participates, the more friends and social connections via one’s church community one will have, thus it is a reinforcing cycle.

Put in this light, is there really such a mystery that men tend to be less religious than women? I encourage folks to go back to the first blog and consider how the current literature looks in light of this discussion. If you are like me, you will see modern researchers clinging to parts of the “elephant” and claiming partial truths as being the whole. The unified approach starts with the meta-view of the physico-bio-psycho-social elephant and allows one to see how the parts are all inter-related.