Oxytocin

Why Weddings Make Us Feel Good

What blood tests after taking vows tell us about the power of bonding.

Posted April 17, 2014

I traveled for 38 hours to the village of Waterrow, moorland in southwestern England—just to take blood from a wedding party. I hadn't met the bride, Linda, or her fiancé, Nic, nor their family or any of their friends. I was an interloper with a syringe.

Linda is a reporter for New Scientist magazine and she and her editor, Roger Highfield, had been reporting on my discoveries about oxytocin, empathy, and moral behaviors for several years. They had the inspired idea to fly me to Devonshire to attend Linda's wedding and take blood and saliva samples from the bride and groom and their families and friends before and after the wedding. We thought that the joy of their union might cause a spike in oxytocin.

I arranged to borrow an expensive centrifuge from the University of Exeter, and had 30 kilos of dry ice sent from London to Waterrow, a village so small it has no street addresses.

An hour-and-a-half before the wedding, with my lab coat on, I began the five-mile drive to the Tudor manor the bridal party had rented. It would take more than 30 minutes driving down partially paved roads only one car wide, fronted on both sides by eight-foot hedgerows.

As I finally pulled into Huntsham Court, a dilapidated late Anglo-Saxon church set the scene. The church was at the center of an estate first recorded as owned in the 12th century. The manor has been available for rent since the last family member to own it died childless in 1988. He is buried in the churchyard cemetery.

One hundred and sixty guests walked the manor in formal finery. They eyed me, some knowing why I was there, others simply amused at a man in a lab coat walking into a wedding. A room off the grand ballroom had a sign on that read, Science Lab. I unpacked 156 pre-labeled test tubes for blood, and then alcohol preps, band-aids, and everything else I needed and organized them on an ornate refectory table.

Linda went first. I've taken blood from hundreds of people in experiments in the lab and in the field. Less than one out of every hundred of my victims faint. If they go down, I'm ready with orange juice and cookies. For the first time, I had also brought smelling salts with me. Emotions run high at weddings, after all. Linda was gorgeous in her strapless wedding dress and we took blood in the bridal suite.

Twelve other people followed. Beside me was a nurse to draw the blood, and a general practitioner in case we needed more help. We did a second round of blood draws immediately after the vows were said. After her romantic kiss with her new husband, we pulled Linda aside to take her blood again. The doctor, nurse, and I got into a rhythm: They stuck the arms with needles and I jammed tubes on each line. We collected 24 more tubes of blood in 10 minutes.

I kept 52 tubes of whole blood cold in a fancy pot of ice so the faint signature of oxytocin wouldn't vanish. After everyone left, I spun the tubes in the centrifuge in my dining-room science lab and pipetted plasma into microtubes.

Blood and weddings are inextricably linked. Weddings are about sustaining our species by ensuring that couples bond to each other. We are born in blood, and many of us die that way, too. Some traditional cultures hang the marital sheet over a balcony the first morning to evidence that the bride's initiation into reproduction has begun. At this wedding, the bridesmaids' dresses were deep crimson, the color of richly oxygenated blood.

The hard part was over. I just had to transport the samples on dry ice to London and FedEx them home.

The wait was worth it: We found that the bride had a spike in oxytocin immediately after her vows, a 28 percent increase to be exact—the largest of the entire group.

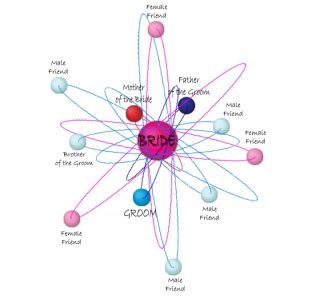

What we found next was more of a surprise: Think about the bride as the sun, the center of the wedding solar system. I plotted how close each member of the bridal party was to the bride and then compared each person's change in oxytocin to Linda's. I drew planets around the bride-as-Sun, with the radius of each "planet" being their compared-to-the-bride change in oxytocin. The closest planet in this loving solar system? The mother of the bride, who was just four units away from Linda with a 24 percent change in oxytocin. Next, at nine units from the bride, was the father of the groom. (The father of the bride declined the blood draws and the mother of the groom had been ill and I chose not to take her blood.) At 15 units away was the groom. Two male friends of Linda's were next, and then her brother. Others fanned out from there, with the largest distance from the bride being a female friend at 45 units.

We found a couple of other interesting things: Not surprisingly, the bride and her mother also had huge spikes in the stress hormones adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol. However, the groom, and most everyone else, was calm. We also measured testosterone and vasopressin in the male members of the bridal party, hormones associated with libido and bonding by males to their mates. The groom stood out on both of these measures—his testosterone spiked 90 percent after the vows. (Perhaps he was fantasizing about the honeymoon.) And his vasopressin showed the biggest drop in the group, 18 percent. Maybe this bonding hormone became less necessary after he publicly bonded with his beloved.

What does this all mean?

We spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to bring those closest to us to one place for the ancient wedding ritual. We hope for the future, and we cry with joy (and jealousy, one half-drunk woman at Huntsham confessed to me). We share the love of the bride and groom as we release oxytocin with them. We are their insurance policy against the inevitable slammed doors, frozen stares, and petty wickedness that every marriage must endure. By attending and physiologically sharing the wedding, we are committing to help keep this couple together with a sympathetic ear or a couch to sleep on if things go wrong. We all have a stake in the survival of the human family and join together as a super-organism to insure people reproduce and invest in their children. We call this marriage.

Eloping may seem simple but few do it. We are social creatures and marriage is perhaps our most important social activity because it is where we see and feel that most human emotion, love.

This was written as the original introduction to The Moral Molecule: The Source of Love and Prosperity. The published book begins with a shorter version of this adventure.