Freudian Psychology

Freud: Fraud or Folk-psychologist?

Research reveals Freudian folk-psychology before Freud.

Posted September 3, 2012

In the previous post, I pointed out that Freud, despite his scientific pretensions, seems to have ended up on the mentalistic side of the two-cultures divide somewhere between poetry and story-telling. But a remarkable study of 176 English-language novels published between 1813 and 1922 suggests that, far from starting out as a scientist and ending up as a story-teller, Freud was part of story-telling from the beginning.

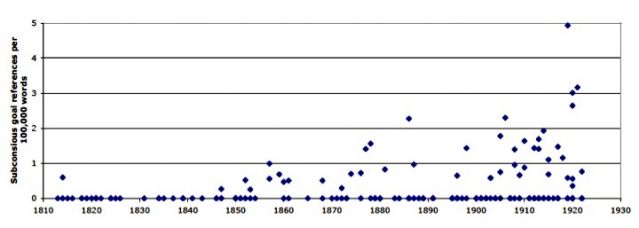

The researchers were investigating literary evidence for what they call “a cultural theory of mind,” or what might alternatively be called folk-psychology. Specifically, they programmed computer software to search the texts “To explore the way that people use language related to the Freudian notion of a subconscious goal.” The texts studied consisted primarily of American and British novels, all of which appeared on at least one “great books list” of the 19th and 20th century and which were available electronically, with an average of 118,000 words per novel, totalling over 20 million words. The researchers report “a gradual shift beginning in the middle of the 19th century that continues to grow into the 20th century through the last of our data points [see below]. We believe this evidence argues for a “Pre-Freudian Shift” in the mental models that people had about their capacity to be aware of their own desires.” They conclude that, “From this perspective, the work of Freud can be seen in a context of widespread cultural change, as an effect rather than an instigating force.”

As W. H. Auden put it, Freud may indeed have been not so much a person as “a whole climate of opinion,” but what this research establishes is that this climate-change in folk-psychology began long before he patented it, and would have happened naturally, even if Freud had never turned psychoanalysis into the most successful and profitable franchise in psycho-therapy.

The novel that illustrates this best is perhaps Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu: the work which many would regard as a culminating achievement of the genre, and perhaps the greatest of all twentieth-century novels. It is certainly the longest, amounting to one-and-half million words in seven volumes, and with a cast of some two thousand characters. Although not directly influenced by Freud’s writings despite being published between 1913 and 1927 when Freud's fame was at its height, you could argue that Proust's great masterwork is also in many ways one of the most Freudian of novels, thanks to its central themes of memory and reminiscence—from which, famously according to Freud, hysterics mainly suffer.

At the very least, you could see it as a work of Freudian folk-psychology, and needless to say, “language related to the Freudian notion of a subconscious goal” abounds. But there is much more: what Freudians would call the family romance of the narrator, and his separation anxiety from his mother; psycho-dramas and acting-out of ambivalence and compulsions; narcissism, egoism, jealousy and paranoia; sexuality, sexual perversion, and homosexuality; and—especially in its last volume—the return of the repressed and an attempt to come to terms with the past by way of not so much a cathartic “talking cure” as a writing one. In Proust, as in psychoanalysis, to remember is to heal as Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen so memorably put it.

Indeed, as Borch-Jacobsen shows in his landmark study of the case of Anna O./Bertha Pappenheim—the germ-cell from which the Freudian cancer of the mind metastasized—Freud and his colleague Breuer were story-tellers from the start. In colloquial English, “story-teller” is a euphemism for liar, and even the fanatically faithful Kurt Eissler was forced to admit that the version of the Anna O. story told by Freud was “false throughout.” It certainly was novelistic—and even romantically so—involving as it did Anna O’s hysterical pregnancy with Breuer’s imagined child and his flight following his wife’s ensuing suicide-attempt to a second honeymoon in Venice, where the conception of a daughter provided a suitably happy ending. Proust couldn't have done better!

Perhaps the fairest conclusion—and certainly the one warranted by the current status of Freud in our collective mentality—is to regard the whole of psychoanalysis as modern folk-psychology, originating in the expanding universe of nineteenth-century literacy—and in the novel in particular—and culminating in the twentieth-century’s greatest folk-psychotherapeutic myth: that of the “talking cure.”

(With thanks to Graham Rook for bringing the study of the novels to my attention.)