Cognition

April Fools!

The disappearing rhino, Van Gogh’s ear, and an alligator stuffed with gold

Posted March 29, 2013

Some pranks take careful spadework and preparation, as I discovered for myself. Once, while staying with friends—passionate tennis players who detested the on-court tirades and pouting of court celebrities—I rose very early each morning to teach their pet parrot, Hugo, to say “John McEnroe, Birdeee!” But I can’t hold a candle to Hugh Troy, the painter, magazine illustrator, and children’s book author who reputedly became the greatest practical joker of the 20th century. If you like pranks, I can recommend a book by his son, Con Troy, titled Laugh with Hugh Troy. Con writes that his father pulled a number of memorable pranks that began in 1922 during his freshman year at Cornell. Talk to a Cornell grad, and you’ll find that the stories still circulate.

One of Troy’s best pranks involved the rhino in the lake. From Cornell’s faculty club Troy borrowed an old-fashioned umbrella stand made from a rhinoceros’s foot. After a snowstorm, Troy used the stand to imprint prominent footprints that led to a rhino-shaped hole that he’d cut in the ice of Beebe Lake, the source for the university’s drinking water. Students who soon came upon the tracks imagined the worst. The clincher came when the bio department examined the footprints, authenticated them, and advised caution at the tap!

On another occasion Troy borrowed galoshes from a notoriously absent-minded professor, painted them over as big, hairy feet with permanent paint and then covered that image with a plain water-soluble layer. When it rained, the outer layer rinsed away and the professor appeared to be walking through campus puddles barefoot. Cornell was not amused by this or other pranks, however ingenious, and eventually tossed young Hugh out. But they didn’t end his career as a prankster.

Years later, while working as a sought-after magazine illustrator and interior decorator in Manhattan, the inventive Troy kept up his old tricks. He coped with the daily problem of finding a New York parking space by carving a hyper-accurate fire hydrant from balsa wood and painting it red. Before he pulled out of a parking space, he’d pull the phony fire-plug from the trunk of his car and place it on the sidewalk. When he returned, he’d park in the empty space, then pick up the hydrant and put it back in the trunk.

I rank this next prank of Troy’s as my personal favorite because it recruited a museum into the chicanery. Troy along with a group of conspirators carved a tolerably real-looking human ear out of a beef brisket that they bought at a Manhattan deli. Then they installed the fake ear in a museum display case. Disguised as museum staff, the group smuggled the case, complete with a case label that read “Vincent Van Gogh’s Ear, c. 1888,” into an exhibit that the Museum of Modern Art had assembled from their collection of the famous painter’s works. Curators, so the story goes, were not amused.

Though brilliant, Hugh Troy held no monopoly on clever pranks, and here’s a final story to prove it.

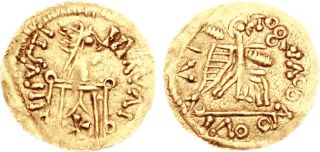

When I was young, my extended family split the cost of renting a substantial beach house of the kind that was typical of the faded glory of the Jersey Shore. All the aunts and uncles and all the cousins would gather, economically. This particular ramshackle old cottage featured a second-floor balcony inside that framed a central great room dominated by a fireplace and its three-story chimney. My cousin Billy, an inveterate prankster—a trait he shared with my grandfather—spied a stuffed alligator that someone had long ago hung inaccessibly high up on the stonework. Rummaging in an attic, he also found an ancient, leather-bound, guest register, a parcel of letters, and a box of yellowed stationery from the 1920s. Emulating handwriting from one of the letters, he forged a note, dated November 3, 1929, that explained how the writer—“Chauncey”—had gotten his cash out of the market just before Black Monday and illegally converted it to gold. He’d hid the coins in “uncle Digby’s old alligator.” Billy concealed the letter in the ledger and arranged it so that my aunt Madelyn would find it. My aunts and uncles celebrated by devoting most of the rest of the vacation to thinking up ways they could retrieve and eviscerate the reptile to get at the treasure inside.