Autism

Abraham Lincoln Tops List of Famous Jewish Swimmers!

Famous (name the trait) lists may harm our children as much as they inspire.

Posted January 23, 2017

Spoiler Alert: Abraham Lincoln was neither Jewish nor a champion swimmer.

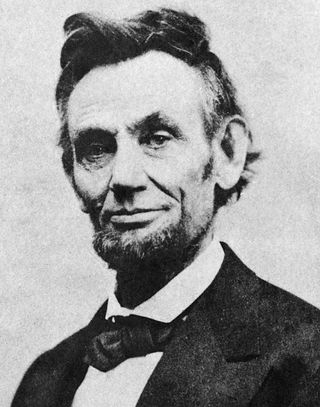

My daughter Sam is bubbling over with pride when she tells me the news. "Abraham Lincoln and I have a lot in common! We both have brown hair, we both oppose slavery, and we're both autistic! I read it on a list of famous people with Asperger's Syndrome." *

The list of famous maybe-Aspies is lengthy. It seems to grow by the day. I used to love reading these compendia too. Smile, feel proud, mail the list to my contacts, repeat. It reassured me to know that my daughter's societally-defined disability was really a gift; if we kept the faith and marshaled her talents, she might some day be the next Einstein, or Newton, or Austen, or Mozart, or Curie, or Dickinson, or Michelangelo, or…George Washington or Ben Franklin? Where did they come from? Not everyone who compiles etiquette lists (like Washington) or pursues his or her interests tenaciously (like Franklin) is autistic. Who is making these lists and, more to the point, why is their credibility so readily accepted?

Because we want to accept them. The lists do not work for me anymore, and my problem is not only that they are ludicrous. I worry about their potential to harm. We hunger to believe in them because they feel like a beacon of light against our fear. But what do these "famous" lists suggest about why we value our children? My daughter is a wonderful girl, but she is not a prodigy. She has her talents, and she has her weaknesses. In all likelihood she will not make it onto anyone's list. Her favorite activities include petting cats, studying images of clothing from the 1860s, and sewing. Nothing jaw-dropping. Of course she may surprise me, but suppose she only meets my expectations. Will she have failed? I explain autism to people and remind them that Bill Gates is likely on the spectrum. What message does she absorb?

Don't get me wrong. I am proud of Sam. But consider for a moment her sister, Kelly. Kelly is a good speller and an enthusiastic (though unexceptional) swimmer. Her classmates do not like her, however, because she won the school spelling bee. I've never felt the need to produce a list of famous Jewish athletes the way I have produced lists of famous autistic people in order to encourage Sam's classmates to interact with her. People like Kelly or dislike her, respect her or do not, because of the person she is, not because of her potential accomplishments as an adult.

Back to Abraham Lincoln. I told Sam that Lincoln did not have Asperger's Syndrome. He was renowned for his folksy humor and ability to entertain diverse audiences with stories tailored to his listeners' interests. According to every definition of autism, no person on the spectrum possesses such social acuity. Still, Sam proudly proclaims her connection to Lincoln almost daily. Obviously it makes her feel special. Obviously she wants this affirmation. After all, she Googled and then memorized the lists without any encouragement. I do understand that she wants successful role models. She is an adolescent. The search for role models, be they athletes, political figures, scientists or Aspies, is important at this stage of forging an identity. Young people need to aspire to something greater than their teenaged selves, and actual success stories serve as an important source of inspiration. I get that. I want Sam to have high self-esteem and believe in her own potential. In fact she does envision herself with many potential futures, and I believe that her identification with some of the people on these lists contributes to her confidence.

But these particular lists, created by non-autistic adults, are not created primarily to motivate our children. They exist to motivate us adults to adjust our own beliefs about autism (at least a particular expression of "high-functioning" autism): Don't you see? This child whom you are judging as socially disabled may create something inconceivable by the rest of us! Recognize his greatness; do not be ashamed of her at public gatherings; remember that these children may someday be more consequential or wealthier than any of us. We have the lists to prove it.

The problem with using the Aspie lists to comfort parents and assure our friends and family that our children are not doomed or defective is that most people with autism, including most Aspies, are not destined for greatness. When I read the comments posted by adults with autism in response to famous autist lists, I am struck by how many of them resent the lists. These adults struggle with the challenges of their diagnosis and see the cherry-picked names as a denial of their own reality. Parents who comment on the lists also often resent them because, they say, the people on the list are not reflective of their children's reality. I wonder if they also realize, somewhere deep-down, that the lists unintentionally diminish their own and their own children's standing. I want people to value Sam simply because she deserves to be valued, not because she'll achieve list-dom.

When I hear parents reciting names from the lists, I hear their apprehension about their child's future and about society's embrace of their child. These parents are realistic in feeling insecure, and that is unfortunate. I just don't believe we are doing our children any favors when we "explain" (read: justify) them by referencing the lists. Wouldn't it be great if our discourse about special needs matured to a point where we, and our children, could feel worthy without having to be exceptional?

*N.B.: I know that AS is no longer recognized as a diagnosis in the DSM-V, but the lists and the identification are still in use by many people.