Education

Learning to Type Before Learning to Write?

Will children soon learn to type more proficiently than they handwrite?

Posted November 6, 2013

One of the most important and simplest lessons in preschool and Kindergarten are the ABCs. At an early age, children learn to recognize the letters, then to print them, in both lowercase and uppercase. If this was 1960, the children would then progress to cursive writing. If cursive writing is disappearing from the public school curriculum, what is next to go? In the next decade, will children learn to type more proficiently than they learn to handwrite?

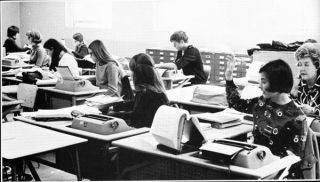

Call me old fashioned, but I learned to type on a typewriter, in high school. At that time, it was a formal and often inconvenient way to write. I was much faster at writing by hand than with a typewriter. Little did I know that the typing would be one of the most important classes I took in high school, in terms of practical application.

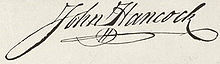

As our next generation of children embarks on the joys of writing, should we be teaching them to learn to type faster, and at an earlier age? Will there be a need for longhand? Will an electronic signature replace the old fashioned John Hancock? What are the cognitive implications for this wave of computer-savvy and fast typing children? Currently, there is now a large amount of research showing the benefits of handwriting, in terms of motor training, as well as more generally in terms of brain development. But it might go beyond just brain development…

The use of the pen versus keyboard allows for a more personalized approach to writing. I remember my mother keeping a handwritten diary, and we all appreciate a handwritten note, or birthday card. Marketers know this too, as we receive junk mail that is addressed using a form of computer-synthesized long hand. Handwriting conveys as certain amount of personalized effort and emotion, and this might be lost in a typed message (after all, the Declaration of Independence was handwritten)!

Finally, the use of a pen can give greater freedom over the confines of a computer keyboard. Stephen King wrote the first draft of the book Dreamcatcher with a notebook and a Waterman fountain pen, which he called "the world's finest word processor." We are more prone to draw diagrams or pictures when not in front of a keyboard, and this can help learning. We can also entertain ourselves with doodling, especially during meetings. In fact, recent research found that students who doodled while listening to a recorded message had better recall of the message's details than those who didn't doodle. These days, when faced with boredom and a laptop or tablet, we mindlessly surf the web, whereas a pen and paper might afford opportunity for less information gathering, and more for creative freedom.

While learning to type may be an essential skill, the typing technology might also change drastically in the next decade. We can already handwrite on our tablet, and maintain much of the personal style that is captured by expressive cursive (perhaps not surprisingly, though, I am writing this on an old fashioned computer keyboard). Medical records have benefitted tremendously in terms of having doctors provide typed prescriptions that can be transmitted electronically, and saved in digitized patient files. In addition, there is less confusing when trying to read a tired physicians handwriting. There are many benefits to have information in electronic type, that can be read by human and machines, and this may make the handwritten note obsolete.

Today, our children see us (as parents and teachers) spending large amounts of time typing, to the point that they might think this is a desired skill or our jobs, as opposed to seeing parents using a pen and paper. Recently, my younger daughter learned to write her name in cursive, partly because she has seen us write like this (I guess we also sign a lot of checks). She was so proud to say that now she has her own signature, and I couldn’t help but think how important that was to her.