Bias

Thresholds for Racism

An awareness of history can improve accuracy in detecting racism.

Posted August 20, 2017

For most Americans, the racial epithets by White supremacists at Charlottesville were racist. Blatant forms of racism are easy to identify. Racism is defined as “prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against someone of a different race based on the belief that one's own race is superior.” But racism does not solely reside within White supremacists.

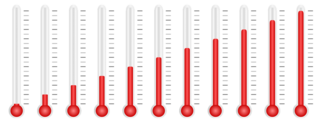

Racism has been described as a disease that everyone in the United States is exposed to. Everyone is racist to some degree. Racism is a continuum. White supremacists are at the extreme end. Most other people are less racist, but still have some racism in them. Everyone tends to favor their own group. Racism is not a rare disease. It is more like the common cold.

Whites tend to have higher thresholds for racism than people of color. For many Whites, only blatant racism qualifies as racism. Subtle forms of racism do not. Not calling a person for an interview with a “Black sounding name”, despite having an identical resume to someone with a “White sounding name”, is an example of subtle racism.

Psychological science reveals three reasons why Whites have high thresholds for racism. One reason is self-protection. Many Whites are very concerned about appearing racist. If racism is limited to blatant and extreme forms of behavior, then they don’t have to see themselves as racist.

Another reason for high thresholds for racism is lack of experience. The American Psychological Association found in a national survey that Whites experience less race-based discrimination than people of color. Less experience with racism results in less sensitivity to it.

A third reason for high thresholds for racism is lack of awareness. Research indicates that both Whites and Blacks who could not distinguish historical facts from fiction about racism were less likely to detect racism on a subsequent test.

- An example of an historical fact is, “The F.B.I. has employed illegal techniques (e.g., hidden microphones in motels) in an attempt to discredit African American political leaders during the civil rights movement”.

- An example of a false statement is, “African American Paul Ferguson was shot outside of his Alabama home for trying to integrate professional football”.

- An example of racism from the test is, “Several people walk into a restaurant at the same time. The server attends to all the White customers first. The last customer served happens to be the only person of color".

The good news is both Whites and Blacks who could distinguish fact from fiction about racism were better able to accurately detect racism.

Repudiating White supremacists and stopping there will have a small impact. White supremacists are a small group. Focusing on racism that is subtle and more widespread is needed.

These three steps may help:

- Let go of the idea that you are not racist. Everyone has some level of racism in them. “Color blindness” doesn’t make racism disappear. Similar to physical color blindness, just because one person can’t see something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

- Listen to others who have experienced racism and may know more about it than you. Don’t dismiss them as overly sensitive. Take them seriously.

- Learn about the histories of ethnic groups other than your own. Listen to people in other groups and seek out other resources, such as educational videos or civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP. Everyone can become less racist.

References

American Psychological Association (2016). Stress in America: The impact of discrimination. Stress in America™ Survey.

Carter, E. R., & Murphy, M. C. (2015). Group‐based differences in perceptions of racism: what counts, to whom, and why?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9, 269-280. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12181

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 575-604. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

Nelson, J. C., Adams, G., & Salter, P. S. (2012). The Marley hypothesis: Denial of racism reflects ignorance of history. Psychological Science, 24, 213–218. doi: 10.1177/0956797612451466

Neville, H. A., Awad, G. H., Brooks, J. E., Flores, M. P., & Bluemel, J. (2013). Color-blind racial ideology: Theory, training, and measurement implications in psychology. American Psychologist, 68, 455–466. doi: 10.1037/a0033282

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2007). Negotiating interracial interactions: Costs, consequences, and possibilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 316-320. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00528.x