Media

The Realm of the Emoji

Why and how has the emoji taken the world by storm?

Posted April 8, 2016

An emoji is a glyph encoded in fonts, like other characters, for use in electronic communication. It’s especially prevalent in digital messaging and social media. An emoji, or ‘picture character’, is a visual representation of a feeling, idea, entity, status or event. From a historical perspective, the first emojis were developed in the late 1990s in Japan for use in the world’s first mobile phone internet system. There were originally 176, very crude by today’s standards.

In 2009, the California-based Unicode Consortium, which specifies the international standard for the representation of text across modern digital computing and communication platforms, sanctioned 722 emojis. The Unicode approved emojis became available to software developers by 2010, and a global phenomenon was born. Today, there are a little over 1,200 emojis available.

The new universal ‘language’?

While emoji is not, strictly speaking, a language, in the way that say, English, French or Japanese are languages, it is certainly a powerful system of communication. English is often said to be the world’s global language, so a comparison is instructive.

English has 335 million native speakers, with a further 505 million speakers who use it as a second language. It’s the primary or official language in 101 countries, from Canada to Cameroon, and from Malta to Malawi - far outstripping any other language. It has been transplanted far from its point of origin - a small country, on a small island - spreading far beyond English shores. But more than the range, English has steadily gained ground in almost all areas of international communication: from commerce, to diplomacy, from aviation to academic publishing, serving as a global Lingua Franca.

But in comparison, emoji dwarfs even the reach of English. The driver for the staggering adoption of emoji has been the advent of mobile computing, especially the smartphone. Emoji was introduced as an international keyboard in Apple’s operating system (iOS) in October 2011. And by July 2013 it had been introduced across most Android operating platforms.

There are different measures for assessing the stratospheric rise of emoji. One factor has been the rapid adoption of smartphones. Today one quarter of the world’s global population owns a smartphone; and based on a survey of mobile computing habits in 41 countries it is estimated that today there are over 2 billion smartphone users with 31% of the global population accessing the internet by smartphone. In terms of specific countries, China exceeded 500 million smartphones during the course of 2014, and it is estimated that India will have over 200 million smartphone users this year, and in the USA the same figure will be achieved by 2017, when 65% of the population of the United States will own a smartphone.[i] In terms of smartphones alone, some 41.5 billion text messages are sent globally every day, using around 6 billion emojis—figures that are mindboggling.[ii]

Emoji all around us

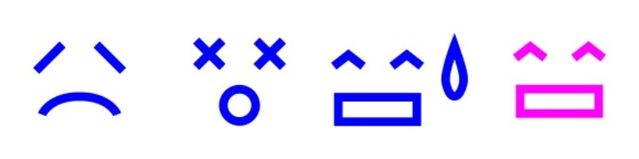

Today emoji is seemingly everywhere, having spread far beyond the messaging systems it was developed for. The New York Subway has now introduced a system, using emoji, to advise passengers of the status of particular subway lines: whether trains are running normally or not. As the NY City website explains: “We're trying to estimate agony on the NYC subway by monitoring time between trains and adding unhappy points for stations typically crowded at rush hour.” [iii] Here’s an example:

Even an institution as august as the BBC is not immune. Each Friday, the Newsbeat page on the BBC website—associated with BBC Radio 1 and aimed at younger listeners—publishes the news in emoji. Radio listeners are invited to guess what the headline means. See whether you can figure out which headline this emoji ‘sentence’ relates to.

1. Four climbers find what they think is a Dodo chick egg. But it’s not. The bird has been extinct for 450 years.

2. One in four people don’t know the Dodo is extinct, a poll finds.

3. Four children win a science competition to genetically recreate the Dodo.

(The correct answer is 2).

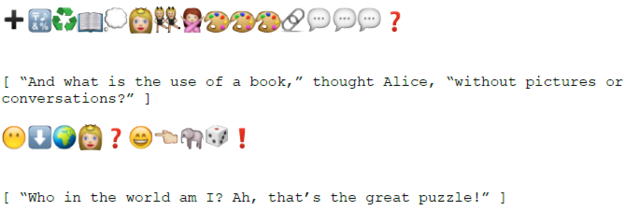

Moreover, the literary canon is not excluded: a visual designer with a passion for emoji has translated Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, a book of 27,500 or so words, into a pictorial narrative, consisting of around 25,000 emoji.[iv] Some example emoji ‘sentences’ are below:

Frivolous or the future?

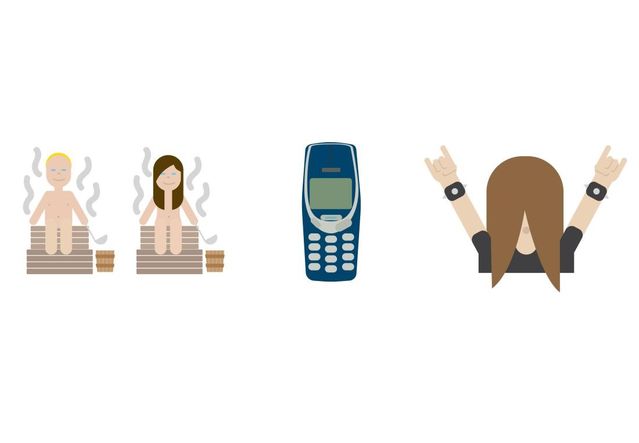

A common question that people ask is whether anyone—you or I—can simply create their own emojis? The short answer is yes. For instance, Finland, on behalf of the Finnish people, has created its own set of national emojis that express Finnish identity. These include emojis of people in saunas, of a Nokia phone and of a headbanger.

But while Finland was the first country in the world to embrace its national identity through emojis, you or I won’t be able to text one another the headbanger emoji anytime soon. And that’s because the Finnish emojis have not been officially sanctioned by the Unicode Consortium—and Finland has no plans to submit them for consideration.

A new emoji has to meet various criteria to become a candidate emoji. And only after a lengthy vetting process, taking around 18 months, does a successful candidate emoji pass muster. Even then, it can take still longer for a newly sanctioned emoji to make it onto our digital keyboards - once approved, emojis can take several operating system - updates, and sometimes several years, to make it onto a smartphone or tablet computer near you. So, for now, at least, Finland’s bespoke emojis are classed as ‘stickers’: bespoke images that have to be downloaded as part of an app, in order to be inserted them into text messages.

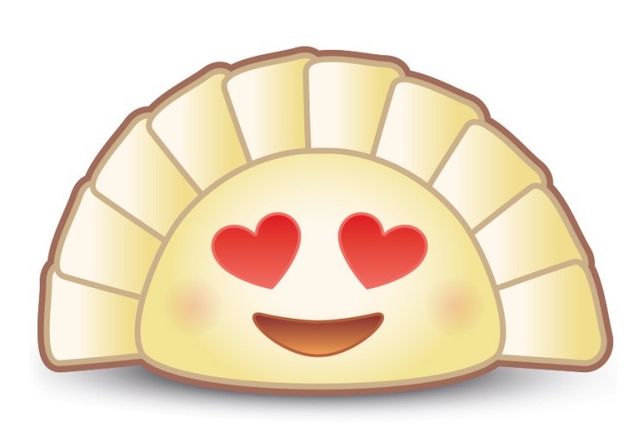

On January 25th 2016, a Chinese - American businesswoman, YiYing Lu, from San Francisco, succeeded where Finland had declined to tread. Supported by a publically-funded kickstarter campaign, Lu succeeded in having a dumpling achieve official emoji candidate status. And if successful, the proposed dumpling is set to become a bona fide emoji by the end of 2017. In so doing, it would join a growing catalogue of food emojis, including pizza, hamburger, doughnuts and even a taco glyph.

The entire emoji vetting process is controlled by a handful of American multinational corporations, based in California. And there are strict qualifying criteria for new emojis: they may not depict persons living or dead, nor deities, for instance. This is why there is no Buddha, or Elvis emojis. Moreover, a candidate emoji must be deemed to have widespread appeal. On this score, the proposal for a dumpling emoji looks to be a strong candidate. A dumpling - a dough filled food parcel - is popular around the world, with exemplars ranging from Italian ravioli to Russian pelmeni, to Japanese gyoza. In Argentina there is empanadas, Jewish cuisine has kreplach, in Korea there is madoo and China has popstickers. But when Lu, an aficionado of Chinese dumplings, attempted to text a friend about the dish, she noticed there wasn’t an emoji she could use.

In early 2016, the fact that the dumpling had officially achieved candidate emoji status in California hit the headlines around the world, from New York, to London, to Beijing; even the broadcast media got in on the act. I was invited onto BBC Radio to discuss the success of the Dumpling Kickstarter project, headlining with Lu herself. The Kickstarter campaign - to raise the necessary funds to prepare the proposal - had been a self-evident success, achieving over $12,000 and reaching its target within a few hours of going live. But the headlines beg the very question: why all the fuss about dumplings? Isn’t this simply frivolity gone mad, an expensive bit of silliness?

On the contrary: emoji matters. The Dumpling Project stands for far more than a simplistic bid to have the favourite food of a Bay area business woman become sanctioned as an emoji. It is an instance of internet democracy at work: indeed, the slogan of the project was ‘emoji for the people, by the people’.

One reason why emoji matters is the following; love it or loathe it, emoji is today the world’s global form of communication. A quarter of the world’s population owns a smartphone, and over 80% of adult smartphone users regularly use emoji, with figures likely to be far higher for under 18s. In short, most of the world’s mobile computing users use emoji much of the time. And yet, the catalogue of emojis that show up on our smartphones and tablet computers - the vocabulary that connects 2 billion people - is controlled by a handful of American multinationals - eight of the eleven full members of the Unicode Consortium are American: Oracle, IBM, Microsoft, Adobe, Apple, Google, Facebook and Yahoo. Moreover, the committee reps of these tech companies are overwhelmingly white, male, and computer engineers - hardly representative of the diversity exhibited by the global users of emojis. Indeed, as of 2015, the majority of food emojis were associated with North American culture, with some throwbacks to the Japanese origins of emoji (such as a sushi emoji).

Hence, one motivation for the Dumpling Project was to ensure better representation. Of course, on its own, a campaign and proposal for a new food emoji cannot do much. But as an appeal to global cultural and culinary diversity, and as call for better representation of this diversity, the dumpling is a powerful emblem. Emoji began as a bizarre little known North Asian phenomenon; since, control has come to rest in the hands of American corporate giants. Dumplings, on the other hand, in their various shapes and guises are truly international and get at the global nature of emoji.

Perhaps more than anything, the Dumpling Project is fun; and in terms of emoji, a sense of fun is the watchword. While these colourful glyphs add a dollop of personality to our digital messaging, the Dumpling Project makes a powerful point without resorting to burning either bras or effigies. It avoids gender, religion or politics in conveying a simple message about inclusiveness in the world’s most widely used form of communication. And in the process, it provides us with an object lesson in the unifying and non - threatening nature of emoji. Perhaps the world can, indeed, be united for the better by this new, quasi-universal form of communication.

Communication and emotional intelligence

Setting aside dumplings, one of the serious questions surrounding the rise and rise of emoji is this: Why has the uptake of emoji grown exponentially: why is a truly global system of communication? Some see emoji as little more than an adolescent grunt, taking us back to the dark ages of illiteracy. But this prejudice fundamentally misunderstands the nature of communication. And in so doing it radically underestimates the potentially powerful and beneficial role of emoji in the digital age as a communication and educational tool.

All too often we think of language as the mover and the shaker in our everyday world of meaning. But, in actual fact, most of the meaning we convey and glean in our everyday social encounters, comes from nonverbal cues. In the spoken medium, gesture, facial expression, body language and speech intonation provide a means of qualifying and adjusting the message conveyed by the words. A facial wink or smile nuances the language, providing a crucial contextualisation cue, aiding our understanding of the spoken word. And intonation not only ‘punctuates’ our spoken language—there are no white spaces and full - stops in speech that help us identify where words begin and sentences end—intonation even provides ‘missing’ information not otherwise conveyed by the words.

Much of our communication is nonverbal. Take gesture: our gestures are minutely choreographed to co-occur with our spoken words. And we seem unable to suppress them. Watch someone on the telephone; they’ll be gesticulating away, despite their gestures being unseen by the person on the other end of the line. Indeed, if gestures are suppressed, in lab settings say, then our speech actually becomes less fluent. We need to gesture to be able to speak properly. And, by some accounts, gesture may have even been the route that language took in its evolutionary emergence.

Eye contact is another powerful signal we use in our everyday encounters. We use it to manage our spoken interactions with others. Speakers avert their gaze from an addressee when talking, but establish eye contact to signal the end of their utterance. We gaze at our addressee to solicit feedback, but avert our gaze when we disapprove of what they are saying. We also glance at our addressee to emphasise a point we’re making.

Eye gaze, gesture, facial expression, and speech prosody are powerful nonverbal cues that convey meaning; they enable us to express our emotional selves, as well as providing an effective and dynamic means of managing our interactions on a moment by moment time - scale. Face - to - face interaction is multimodal, with meaning conveyed in multiple, overlapping and complementary ways. This provides a rich communicative environment, with multiple cues for coordinating and managing our spoken interactions.

Digital communication increasingly provides us with an important channel of communication in our increasingly connected 21st century social and professional lives. But the rich, communicative context available in face-to-face encounters is largely absent. Digital text alone is impoverished and emotionally arid. Digital communication, seemingly, possesses the power to strip all forms of nuanced expression even from the best of us. But here emoji can help: it fulfils a similar function in digital communication to gesture, body language and intonation, in spoken communication. Emoji, in text messaging and other forms of digital communication, enables us to better express tone and provide emotional cues to better manage the ongoing flow of information, and to interpret what the words are meant to convey.

It is no fluke, therefore, that I have found, in my research on emoji usage in the UK, commissioned by TalkTalk Mobile, that 72% of British 18-25 year olds believe that emoji make them better at expressing their feelings. Far from leading to a drop in standards, emoji are making people - especially the young - better communicators in their digital lives.

[i] http://www.emarketer.com/Article/2-Billion-Consumers-Worldwide-Smartpho…

[ii] Swyftkey April 2015

[iii] http://www.wnyc.org/story/your-subway-agony/ (accessed 8th July 2015 7.30pm BST).

[iv] http://joehale.bigcartel.com/product/wonderland-emoji-poster