Career

Are You or Your Boss a Benevolent Tyrant?

How to build relationship sanity in the workplace

Posted April 11, 2016

"I might be a benevolent tyrant, but make no mistake: I’m still a tyrant.”

This was a major theme of the talk Mike typically gave his coworkers at the outset of a new project taken on by his organizational consultation group.

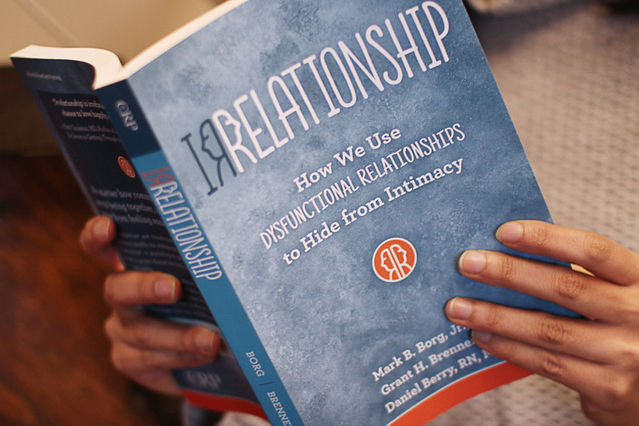

A lot of our writing concerns how irrelationship affects romantic relationships; but it can be a part of virtually any kind of connection between or among people, including coworkers in the work setting. But it always has the same purpose: preventing exposure of one’s heart—or, one’s feelings and needs, if you prefer—to the vulnerability that comes with emotional investment in others. The day-by-day sharing of space and tasks, therefore, makes the workplace a powerful incubator for protective song-and-dance routines of irrelationship. Crucially, the distancing such routines creates often prevents shared enterprises from getting off the ground.

Tyrannical as his “operating system” was, Mike was forced to step outside his comfort zone to learn how to make a shared project—a successful project—work. "I used to spend a lot of energy trying to convince myself that this company is a success solely because of my ideas and my hard work. To keep myself from freaking out, I’d ignore the abilities and contribution of my partners, James and David. But the truth is, if it weren’t for what they bring to the table, this company would probably still be where it started: in my head.”

Analyzing how interpersonal dynamics from our past lives play out in the present—what psychoanalysts call enactment—is a pragmatic tool for figuring out what doesn’t work in our adult relationships so we can move beyond doing what we’ve always done, put an end to self-defeating habits, and develop a more effective interpersonal style. We learn how our patterns of relating to others “in the now” is a routine we developed as children to shield us from the anxiety we felt when, for whatever reasons, our caregivers’ behavior made us feel insecure or even unsafe.

Once we are able to see ourselves through the irrelationship lens, connecting the dots is fairly easy. We have to ask ourselves, “Are we willing to square off with these challenging truths?” We come to see how inability to trust our caregivers as small children led to a need to defend against disappointment from actual or potential close associates as adults. In the work setting, we enact this though situations in which we don’t share tasks, accept support from others, or even allow them to take pride in successes.

Mike reflected, "In two past start-ups, I was always imposing my will on the people I worked with, but would try to make it look like I was taking care of them. But what I was really doing was keeping them in the dark about what was really going on in our projects. So there was no real cooperation or sharing of work—not even shared problem-solving. You know what happened. Nobody knew what ‘the whole picture’ was except me. Everybody else was basically working in a vacuum. Well, I learned the hard way, it doesn’t work. But at the time that didn’t stop me for blaming them when things fell apart. I’d accuse them of not being team players! It was totally insane.”

When Mike’s third company, which he tried to run according to his irrelationship routine, started unraveling, he finally had to become willing to allow himself to validate his partners’ work, and even to accept that their contributions gave them a legitimate stake in outcomes. It didn’t change all at once, though, and upticks in Mike’s anxiety can still drive him to try to take control of everything again.

“But I’ve gotten much better,” he winked, jokingly alluding to his ongoing work on this aspect of his professional approach.

"In my other two start-ups, I had to make every single decision, which, ironically, blinded me from what was really going on in the company. And that was true both from a business standpoint and with the people I was supposedly working ‘with.’ I never gave a thought to what was going on in anybody’s head except mine. And the result was that I pretty much smothered two promising ideas for new businesses—and, by the way, my coworkers’ enthusiasm—almost before my ideas saw the light of day.”

When things threatened to go south in his newest company, how did Mike and his associates change the outcome?

Setting aside regular times in the work week to use a technique called the “40-20-40,” or "meeting-in-the-middle," Mike, James and David learned, via strictly timed periods of mutual sharing (a reciprocal and balanced giving and receiving that we refer to as relationship sanity), to take inventory of their own contributions to their work together, as well as to assess feelings they were having, positive and negative, that impacted on work-flow. This simple practice cleared a space for mutual acceptance and valuing of each other’s contributions, with the added, crucial benefit of resolving disruptive feelings.

"Before I—no, we—started using the 40-20-40, I couldn’t let anybody else’s contribution to a project ‘matter.’ All that mattered was what I was feeling at any given moment. I was so isolated that I couldn’t see that I was creating the same scenario that ruined past business relationships. I was preventing anybody else from knowing what was going on—or actually getting done—under the guise of this fake caretaking. And I damn near blew it out of the water. Again.”

To order our book, click here. Or for a free e-book sample, here.

Join our mailing list: http://tinyurl.com/IrrelationshipSignUp

Visit our website: http://www.irrelationship.com

Follow us on twitter: @irrelation

Like us on Facebook: www.fb.com/theirrelationshipgroup

Read our Psychology Today blog: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/irrelationship

Add us to your RSS feed: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/irrelationship/feed

The Irrelationship Blog Post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publisher/Psychology Today. The Irrelationship Group, LLC. All rights reserved.